Interview

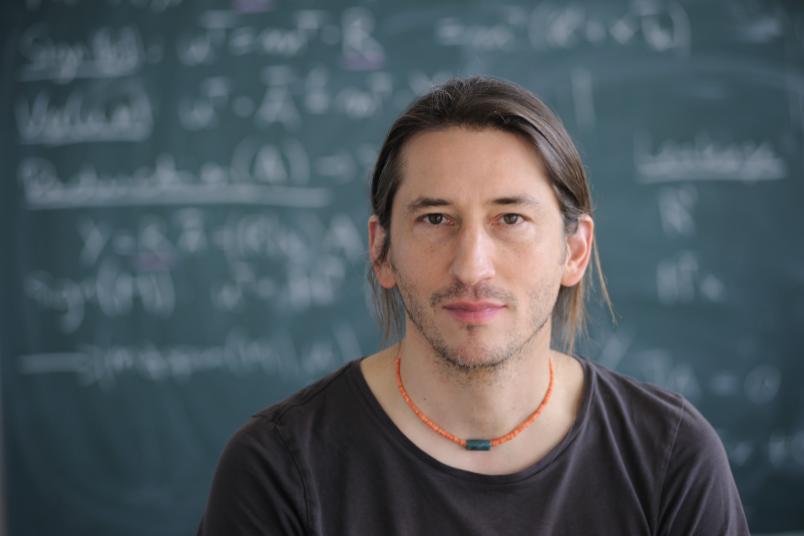

Research at the edge of theory

Eike Kiltz studies the hardest problems in mathematics – research doesn’t get any more theoretical and abstract than that. A glimpse into his work routine.

Prof Kiltz, you develop novel cryptographic algorithms, based on particularly hard mathematical problems. Are pen and paper all that you need for your work, or do you also use computer simulations?

We don’t use simulations at all. There are some research groups in the field of mathematics who deploy computer simulations or implement things in practice. But my group carries out research at the very edge of theory; it doesn’t get any more theoretical than that. We sit around with pen and paper and think.

That means you don’t use the computer at all, then.

Only if I want to write an email or if I need a word processing software. Or if I open an algebra programme to work out five times seven or to factor a polynomial; something trivial, that is, which I’m too lazy to work out in my head.

That sounds as if you did a lot of your work on your own – or do you think together with others?

That depends on the people. Personally, I prefer doing the thinking on my own, if I have the time. Other people want to engage in dialogue. Our discipline can be fairly communicative at times. But sometimes you have to lock yourself in for a few hours or even days to solve a problem.

In many disciplines, results have to be interpreted. Does this also apply to the things that you eventually write down on a piece of paper?

We eventually write down a theorem which states that B follows A. If the proof has been properly constructed, it is irrefutable. It is true. That’s the beautiful thing about mathematics – that’s what I love about it.

Does that mean that all algorithms that you develop are irrefutable in practice? Because you have proved beyond doubt that they are secure?

It happened before that somebody cracked a new cryptographic scheme that I’d developed. Even though I had proved that it is secure. What happened? In the proof, I had assumed certain conditions which the attacker didn’t adhere to. The next time the model would have to be accordingly expanded to include those conditions into the proof.

Abstract, theoretical research such as this is not for everyone. Why did you decide to pursue it?

I always used to be quite good in maths at school. In other subjects, not so much. I would have loved to become a professional football player, but I didn’t have what it takes. It was a pragmatic decision to do what I’m good at. And now I’m here. I’ve never had any regrets.