Neuroscience How children perceive faces

Humans are experts in facial perception. But not from birth. At which point do children become as skilled at it as adults?

Developmental psychologists are often interested in newborn infants and study children between birth and two years. They investigate at which age children develop certain skills, for example facial perception.

However, the brain does not simply switch on an ability like that and it emerges fully formed. Rather, it becomes more and more refined as development progresses. We learn, for example, to tell people apart who look very much alike and to recognise people after they had cut and dyed their hair.

Two opinions among researchers

Therefore, the question at which point humans are able to perceive faces cannot be answered by naming one specific age. It is not an all-or-nothing process, according to RUB developmental neuropsychologist Prof Dr Sarah Weigelt. She intends to find out at which point children are on par with their parents when it comes to facial recognition. She doesn’t test newborn infants, but five to ten-year-olds.

“The scientific community is split into two factions,” explains Sarah Weigelt. “One group says that the process is completed by the age of five.” Subsequently, people get better at recognising faces only because attention and memory improve, even though development is completed in the brain areas involved in face perception. “Other researchers believe that humans are programmed to recognise faces to such an extent that the brain continuously increases its relevant capacity until the age of 32,” she adds.

[einzelbild:]

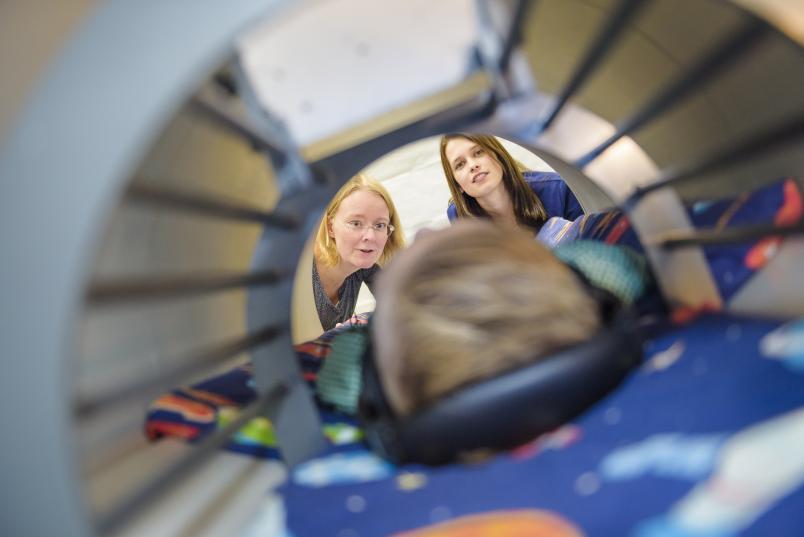

Sarah Weigelt and PhD student Marisa Nordt want to learn more about it. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (functional MRI), they analyse the processes that take place in the brain of adults and seven-year-olds while they watch faces. They thus gather information regarding the activity of individual brain areas at any given moment. The researchers focus mainly on analysing the so-called Fusiform Face Area, a small area in the temporal lobe, which is specialised for facial perception.

How the brain adapts to viewing faces

They take advantage of a habituation effect: brain areas that are confronted with the same stimulus repeatedly respond to it less and less strongly. In other words: if we see the same image of a person again and again, the activity in the brain area decreases.

Weigelt and Nordt presented their test participants with photos of faces, always six images in close succession within the space of 12 seconds. That was followed by a pause, and subsequently by a new 12-second block with six photos, then another break and so on. There were three types of image sequences: in the first one, all six photos in a block were identical. In the second image sequence category, all six photos were of the same person, but the images were different. In the third category, the photos showed different people.

Comparing children and adults

Sarah Weigelt and Marisa Nordt knew from previous studies that the face area in adults indicates a strong habituation effect if they view six identical photos in succession. This effect does not present if images of different people are displayed.

The researchers were mainly interested in image sequences of six different photos of the same person. If adults were shown different photos of the same person, a habitual effect set in that was less strong than when viewing identical photos of one person. But what about seven-year-old children? Do they present the same habituation effects? That would indicate that their facial perception is as highly developed as that of adults.

Marisa Nordt and Sarah Weigelt conducted the study described above with both adults and children and compared the results. In order to make sure that the little test participants wouldn’t get scared during the examination in the confined and loud MRI scanner, the psychologists did dry-runs with the children in a RUB room specifically equipped for that purpose.

To this end, the workshop team at the Faculty of Psychology recreated a MRI scanner. It looks like the real device and imitates the sounds it makes, but it doesn’t record any data. The children had thus the chance to get used to the exam situation beforehand.

Fifteen children in total took part in the study. They presented the same habituation effect as adults if they viewed six identical photos of one person. The effect did not occur when they were shown photos of different people – this corresponded with the results in the adult cohort. “The interesting results were generated in the sequences with different photos of the same person,” says Weigelt. At first glance, everything was the same in seven-year-olds and in adults: a habituation effect that was less strong than in case of identical photos.

A closer look reveals that the results in children and adults were caused by different factors.

Sarah Weigelt

“A closer look reveals, however, that the results in children were caused by a different factor,” explains Weigelt. The psychologists did not only view the mean of the data set, but they also analysed the brain activation of individual participants. If adults looked at different photos of the same person, a habituation effect occurred in all of them, which was less strong than when viewing identical photos of one person. That was not the case in children.

Some seven-year-olds presented no habituation effect whatsoever, others a fully-fledged one. “If children see different photos of one and the same person, they appear to say either: this is the same person. Or: these are two different people,” elaborates Weigelt. “There’s nothing in between.” The results thus illustrate that even though seven-year-olds are able to recognise faces, that skill is not fully developed yet.

With regard to other aspects of facial perception, on the other hand, children as young as five are as clever as adults. Marisa Nordt tested, for example, how well children are able to view faces from difficult perspectives.

When kindergarteners draw faces, more often than not it’s from the front. They don’t get the profile view quite right.

Sarah Weigelt

“When kindergarteners draw faces, more often than not it’s from the front,” says Sarah Weigelt, who has observed it in her own daughter. “They don’t get the profile view quite right.” If they attempt it, children will draw a face with the nose seen from the side, but it will still have two eyes. “We hypothesised that people get better and better at recognising faces from difficult perspectives, including the profile view, during childhood,” she adds.

Testing young children with tablets

This theory was not verified in the experiment. Five-year-olds found it more difficult to recognise faces in profile, but the same applied to adults. “Perhaps we have to test children at a younger age,” considers Sarah Weigelt. “But that would render the exam more difficult.”

Her team is currently programming some tests as computer games, for example as a memory or sorting game. Weigelt: “We hope they can one day be used for conducting studies with two and three-year-olds who – fascinated by the technology – would play the games at the tablet.” One thing has become clear: learning facial perception is a gradual process that is not completed by the age of five.