Optogenetics

Controlling nerve cells with light

Anxiety and depression are two of the most frequently occurring mental disorders worldwide. Light-activated nerve cells may indicate how they are formed.

Statistically, every fifth individual suffers from depression or anxiety in the course of his or her life. The mechanisms that trigger these disorders are not yet fully understood, despite the fact that researchers have been studying the hypothesis that one of the underlying cause are changes to the level of the neurotransmitter serotonin for 60 years.

Serotonin system difficult to understand

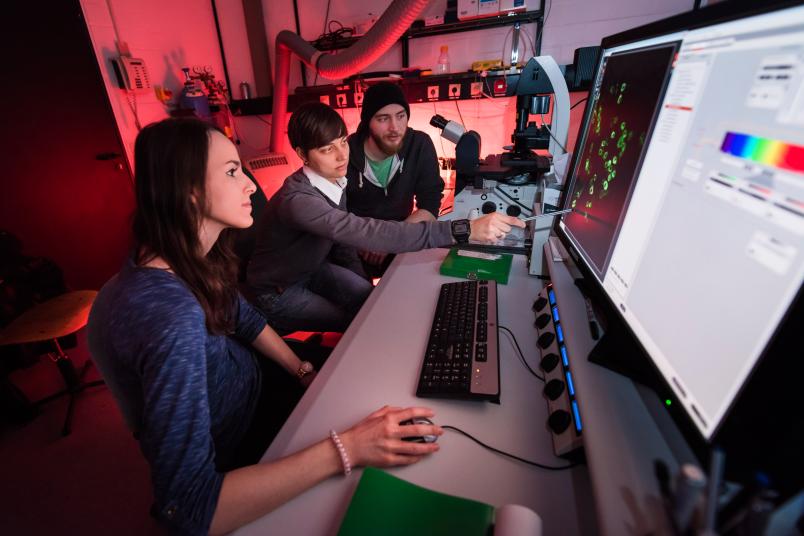

“Unfortunately, it is very difficult to understand how the serotonin system works,” says Prof Dr Olivia Masseck, who is junior professor for Super-Resolution Fluorescence Microscopy since the end of April 2016. She intends to fathom the mysteries of the complex system. The number of receptors for the neurotransmitter in the brain amounts to 14 in total, and they occur in different cell types. Consequently, determining the functions that different receptors fulfil in the individual cell types is a complicated task.

In order to fathom the purpose of such receptors, researchers used to observe which functions were inhibited after they had been activated or blocked with the aid of pharmaceutical drugs. However, many substances affect not just one receptor, but several at the same time. Moreover, researchers cannot tell receptors in the individual cell types apart when pharmaceutical drugs have been applied. “It had been impossible to study serotonin signalling pathways at high spatial and temporal resolution,” adds Masseck. Until the development of optogenetics.

This method has revolutionised neuroscience.

Olivia Masseck

“This method has revolutionised neuroscience,” says Olivia Masseck, whose collaborator Prof Dr Stefan Herlitze was one of the pioneers in this field. Optogenetics allows precise control over the activity of specific nerve cells or receptors with light. What sounds like science fiction, is routine at RUB’s Neuroscience Research Department. Masseck: “Until now, we had been passive observers, and monitoring cell activity was all we could do; now, we are able to manipulate it precisely.”

Understanding the contributions of single receptors

The researcher from Bochum is mainly interested in the 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors, the so-called autoreceptors of the serotonin system. They occur in serotonin-producing cells, where they regulate the amount of released neurotransmitters; that means they determine the serotonin level in the brain.

Normally, 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B are activated when a serotonin molecule bonds to the receptor. The docking triggers a chain reaction in the cell. The effects of this signalling cascade include a reduced activity of the neural cell, which releases less neurotransmitter.

Combining receptors and visual pigments

By modifying certain brain cells in the brains of mice, Olivia Masseck successfully activated the 5-HT1A receptor without the aid of serotonin. She combined it with a visual pigment – so-called opsin. More specifically, she utilised blue or red visual pigments from the cones responsible for colour vision. This is how she generated a serotonin receptor that she could switch on with red or blue light. This method enables the RUB researcher to identify the role the 5-HT1A receptor plays in anxiety and depression.

To this end, she delivered the combined protein made up of light-sensitive opsin and serotonin receptor into the brain of mice using a virus that had been rendered harmless. Like a shuttle, it transports genetic information which contains the blueprint for the combined protein. Once injected into brain tissue, the virus implants the gene for the light-activated receptor in specific nerve cells. There, it is read, and the light-activated receptor is incorporated into the cell membrane.

Anxiety switched off by light

The researcher was now able to switch the receptors on and off in a living mouse using light. She analysed in what way this manipulation affected the animals’ behaviour in an anxiety test, i.e. Open Field Test. For the purpose of the experiment, she placed individual mice in a large, empty Plexiglas box.

Under normal circumstances, the animals avoid the centre of the brightly-lit box, because it doesn’t offer any cover. Most of the time, they stay close to the walls. When Olivia Masseck switched on the 5-HT1A receptor using light, the behaviour of the mice changed. They were less anxious and spent more time in the middle of the Plexiglas box.

These results were confirmed in a further test. Olivia Masseck stopped the time it took the mice to eat a food pellet in the middle of a large Plexiglas box. Normal animals waited between six and seven minutes before they ventured into the centre to feed. However, mice whose serotonin receptor was switched on started to feed after one or two minutes. “This is important evidence indicating that the 5-HT1A receptor signalling pathway in the serotonin system is linked to anxiety,” concludes Masseck.

In the next step, the researcher intends to find out in what way depressive behaviour is affected by the activation of the 5-HT1A receptor. “If the animals are exposed to chronic stress, they develop symptoms similar to those in humans with depression,” describes Masseck. “They might, for example, withdraw from social interactions.”

However, just like in humans, this applies to only a certain percentage of the mice. “Not every individual who suffers from chronic stress or experiences negative situations develops depression,” points out Masseck. What happens in the serotonin system of animals that are susceptible to depression, as opposed to that of animals that do not present any depressive symptoms? This is what the researcher intends to find out by deploying the optogenetic methods described above; in addition, she is currently developing a custom-built serotonin sensor.

Olivia Masseck’s assumption is that her findings regarding the neuronal circuits and molecular mechanisms of anxiety and depression are applicable to humans. Mice have similar cell functions, and their nervous system has a similar structure. The neuroscientist expects that optogenetics will one day be deployed in human applications.

I am convinced that optogenetics will be used in human applications in the next decades.

Olivia Masseck

“Genetic manipulation of cells for the purpose of controlling them with light might sound like science fiction,” she says, “but I am convinced that optogenetics will be used in human applications in the next decades.” It could, for example, be utilised for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s patients, because it facilitates precise activation of the required signalling pathways, with fewer side effects, at that.

We have to discuss in which applications we want or don’t want to use these techniques.

Olivia Masseck

“In the first step, optogenetics will be used in therapy of retinal diseases,” believes Olivia Masseck. Researchers are currently conducting experiments aiming at restoring the visual function in blind mice.

Olivia Masseck is aware that her research raises ethical questions. “We have to discuss in which applications we want or don’t want to use these techniques,” she says. Her research demonstrates how easily the lines between science-fiction films and scientific research can blur.