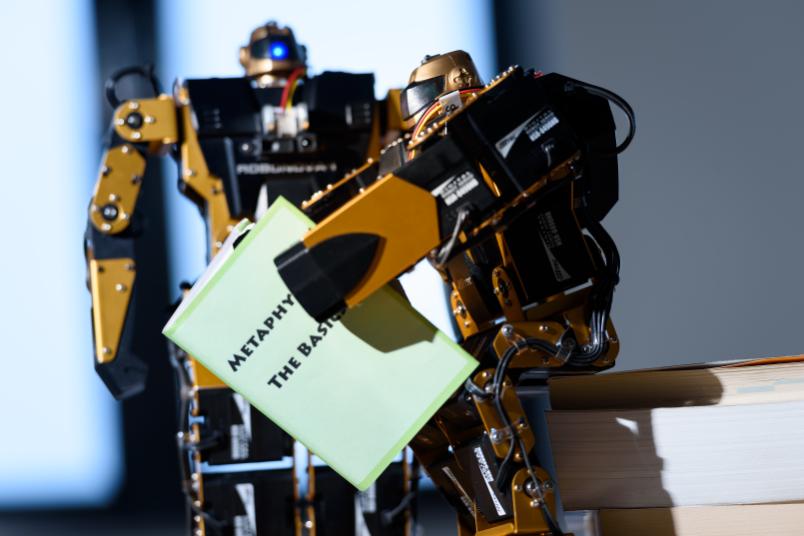

Philosophy The entire knowledge of the world in the computer

For computers to be able to process the complex knowledge of the world, that knowledge has to be explicitly and logically structured and phrased. Philosophers help to achieve precisely that.

In an era when information about consumers is collected during online shopping, one thing is evident: a huge volume of data is generated every day. The sciences, too, collate data: highly diverse and in different formats. But if every discipline only cares for itself, those data are incompatible and cannot be processed or used to solve questions studied by other researchers.

Philosophers are familiar with definitions

Consequently, a common language is necessary; or to put it another way: standards for a consistent representation of knowledge about the world that is gathered by scientists. Researchers from different disciplines work hand in hand with philosophers to achieve this goal. Philosophers are familiar with definitions, categories and logical causations by virtue of their profession. Plato and Aristotle studied ways of describing the world already more than 2,000 years ago, attempting to identify the highest categories for classifying its components.

The language we use for representing the knowledge of the world has to be very simple.

Ludger Jansen

This interdisciplinary collaboration aims at creating so-called ontologies: knowledge representations in the computer for different scientific areas that can be continuously expanded. They are supposed to help render data compatible so that they can be utilised not only by those researchers who had originally gathered them, but also by other work groups.

“The language we use for representing the knowledge of the world has to be very simple, logically structured and unambiguous, in order for computers to be able to handle it and draw conclusions in an automated process,” explains private lecturer Dr Ludger Jansen, currently Interims Chair for Interdisciplinary Questions in Philosophy and Theology at the Faculty of Catholic Theology at Ruhr-Universität. “Ideally, human users should also be able to understand it intuitively.”

Ludger Jansen operates at the intersection between theology, philosophy and informatics.

Such simple descriptions and correlations might include statements like “Living beings are made up of molecules”. However, sometimes linguistic expressions constitute a challenge due to their ambiguous character. Is a disease a property or a process? Is a gene a material object or information content?

Resources from the philosophy of language also come in handy. For example, how can data pertaining to diseases be separated from data pertaining to the names of diseases? “It is correct to say: Hepatitis is localised in the liver,” elaborates Ludger Jansen. “But it is also correct to say: Hepatitis has four syllables. If, however, one concludes on the basis of this information that a four-syllable item is located in the liver, a category error occurs.”

The developers of an ontology discuss such questions in email lists or at congresses until a consensus is reached and the group in charge of the respective ontology writes and implements an update.

Ontologies are not meant to compete against each other

Different disciplines compile different ontologies – interested parties can find them in ontology catalogues or search engines. Individual ontologies are not meant to compete against each other; rather, they are supposed to interlink and complement each other.

Ludger Jansen operates primarily in the field of life sciences, contributing to a wide-spread, fundamental ontology, the Basic Formal Ontology. Currently, he researches into the problem of causal properties. “Here, problems occur if one property can have different effects. A magnet, for example, can both attract and repel another magnet,” illustrates Jansen.

In biology, the theory of evolution has replaced the notion of a designing god.

Ludger Jansen

A lively discussion revolves around biological functions, for example those of organs. “In biology, the theory of evolution has replaced the notion of a designing god. That means that the properties of living organisms have been randomly generated and have proved successful in evolutionary terms. If, however, we use the term ‘function’, this terminology implies that a biological process pursues a specific goal,” explains Ludger Jansen.

This is why philosophers suggested in the past to understand functions, for example those of organs, simply as its causal contributions. But the rhythmic sound the heart makes is likewise a causal contribution of the heart – it is, however, not its function but rather a side effect. This is why other philosophers prefer to define functions as properties that have proved to be successful in evolutionary terms. In this case, malfunctions pose a challenge. Talk of malfunctioning, in turn, is closely linked to the question what it means to call something “healthy”?

The ontology will have grown by another fraction

This, too, is the philosophers’ territory. “The list of possible answers ranges from subjective wellbeing, through functionality for the organism, to what applies in the majority of cases,” ponders Jansen. Together with his interdisciplinary colleagues, he is going to continue discussing the issue until a consensus is reached. Then, ontology will have grown by another fraction.