Latin From world language to analytical instrument

In the past, anyone who wanted to belong to the cultural elite had to study Latin. A lot has changed since then. However, Latin has not disappeared, far from it.

For a long time, Latin was considered the language of the powerful and learned. Not only was it the administrative language of Ancient Rome, but it also spread across the entire Mediterranean region all the way to Northern and Eastern Europe during the Roman Empire.

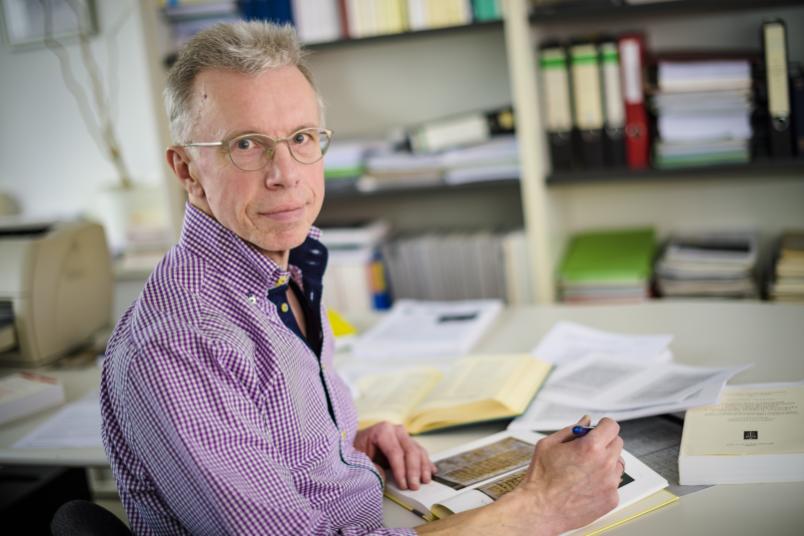

Today, people still encounter Latin at grammar schools or in the field of humanities. But it is only ever used for reading and writing. Nobody speaks Latin as their native language anymore. Prof Dr Reinhold Glei from the Institute of Latin Philology studies how Latin has evolved over centuries and in which contexts it emerged after it ceased to be a world language.

Latin originated in the metropolis of Rome in the Latium region. During the Roman Empire, the language had its golden age between 753 BC and 476 AD. However, as early as 400 AD, Romans started to lose their control over some regions, and their empire began to shrink. In terms of spoken language, local dialects gradually replaced classical Latin. Still, most texts were written in Latin until the Early Modern Period.

“Latin remained the language used by the educated elite in the Western world, and everyone who wanted to be part of the education systems had to study it,” says Glei. It wasn’t until the 16th century that vernacular languages became more widespread in the field of education. However, Latin did not disappear wholly in the following centuries, and it stood its ground next to vernacular languages. But why was Latin still in use?

Reinhold Glei’s research has yielded the first results to answer this question. Analysing Latin texts from the 17th to 19th centuries, he ascertained that they fulfilled a specific function. They served as an instrument that helped understand and translate languages that had hitherto not been well known in the Occidental culture.

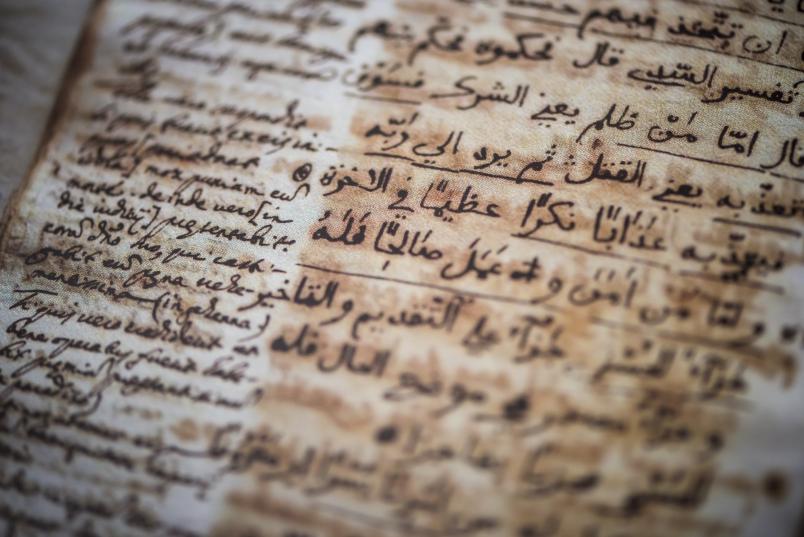

Arabic, Sanskrit, Chinese: these languages were new in Western culture. Their sentence structure and meanings posed a challenge to the scholars. “If the foreign-language texts had been translated into a spoken language such as German, the translator would have been restricted by the respective grammatical structures. Using Latin, the translators had more freedom,” elaborates Glei. Since Latin had long ceased to be a spoken language at that point, translators were able to free themselves from specific rules. Instead, they recreated foreign-language sentences with the aid of Latin. This approach was possible, because native speakers no longer existed who might have taken exception to the unusual syntax in the Latin translations.

Representing linguistic structures

The method offered a considerable advantage to the scholars: they were able to draw up a neutral text, before translating it into their respective vernacular language. Thus, the transportation of structures and meanings from the original into the translation was much more precise. Each spoken language is culturally prejudiced, which spills into the texts. Latin helped sidestep that effect. “It’s interesting to see in what way the language was handled in history and for which purpose it was used,” explains Reinhold Glei.

The researcher refers to Latin in its translation function as epilanguage. “Epi” is “on” or “above” in Greek. “Latin was superimposed over the foreign language, without obliterating that language and its structure. Latin was used as a tool,” says Glei. The latter function constituted a workable way of analysing new languages.

Glei did not come up with the term epilanguage, but he had put it into a new context. Initially, epilanguage was used in the field of psychology to discuss first language acquisition in children. The term refers to the way in which infants subconsciously identify structures in language. Linguists later transferred the term to language itself. This is why the philologist considered the phrase appropriate for describing his analysis results.

In order to study Latin as a translation tool, the Bochum-based researcher compiles analysis examples in various languages. In addition to Arabic and Chinese, he also examines Hebrew, Persian and Georgian texts, to name but a few. To this end, he compares excerpts from the Latin translation with the originals and identifies to what extent the Latin versions reflect the structure of the original language. Glei studied, for example, various Quran translations. “When Christians initially translated the Quran, the texts they created were for the most part ideologically charged. This resulted in corrupted translations,” he says. Using Latin as the epilanguage did not wholly eradicate the problem, but it was possible to represent the structure of the Arabic language in a more neutral manner.

Research into epilanguage is still in its early stages. Reinhold Glei intends to analyse additional Latin translations from various languages, in order to gain a better grasp of the function of epilanguage. He also wishes to study another world language, namely Ancient Greek, in greater detail. His first impression is: “Ancient Greek appears to occur less frequently as epilanguage. This might be because the language is not dead; it lives on in Modern Greek.”

The languages of the powerful and learned today differ from those 2,000 years ago. Still, Latin continues to pop up in our everyday life. Take virus, palace or senior: many modern terms are derived from Latin. The language has stood the test of time over centuries and, even today, can help us understand foreign languages.