Protein research Correct identification of liver cancer

The origins of a tumour are relevant for correct treatment. Proteins provide a clue.

A tumour in the liver – a shocking diagnosis for the affected patients. To doctors, it is initially a question mark, as the full extent of the disease cannot be determined following the detection of the tumour alone.

“Most tumours in the liver form from liver cells, so-called hepatocytes,” explains Prof Dr Barbara Sitek, head of the research group Clinical Proteomics at Medizinisches Proteom-Center at RUB. Some originate in the bile ducts in the liver from the cells that line those ducts, so-called biliary epithelial cells. Moreover, a tumour might occasionally be detected in the liver even though it did not originate there; this is what is referred to as a metastasis.

Tumours that form from pancreatic duct bear a strong resemblance to tumours in bile ducts of the liver, and they can migrate to the liver.

Tumours that form in the pancreas are often very aggressive.

Barbara Sitek

“For the purpose of treatment and diagnosis, identifying the location where the detected tumour originated is of crucial importance,” explains Barbara Sitek. If cancer formed in the liver, the chances to survive the disease are much better than if it originated in the pancreas. Liver cancer can be surgically removed and treated with drugs. Tumours that form in the pancreas, however, are often very aggressive. A mere five per cent of the patients survive the period of five years after diagnosis. “The treatment in these cases does not aim at a cure, but at maintaining the patients’ quality of life as long as possible,” says Barbara Sitek.

Due to the morphological similarities between both tumours, pathologists to date had difficulties verifying the origins of the primary tumour. Funded by Mercator Research Center Ruhr (Mercur), Barbara Sitek and her colleague Dr Thilo Bracht, together with a team from the university clinic in Essen headed by Prof Dr Hideo A. Baba, had therefore embarked on a search for new protein biomarkers. These biomarkers are proteins that typically occur in tumour tissue in larger quantities. Once proteins have been identified that are associated with a specific type of tumour, the different types of tissue can be distinguished.

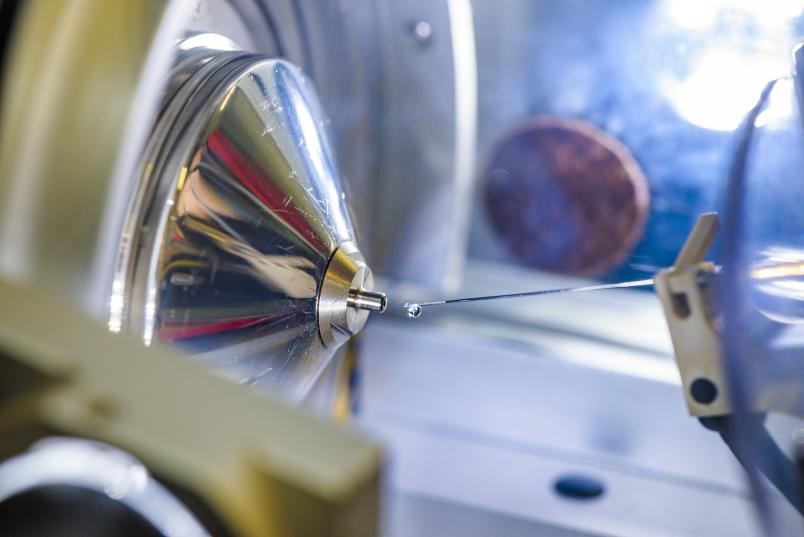

As the university clinic in Essen is specialised in diseases of the liver, the researchers had access to many fresh tissue samples of liver tumours and could analyse them. To ensure that only the tumour cells were examined, the relevant cells had to be isolated from the surrounding tissue in the first step. To this end, the researchers used a special microscope that deploys laser beams for cutting out specific, previously marked areas from tissue layers with a thickness of ten micrometres. Using a laser pulse, the thus removed cells were catapulted into a tube.

In the next step, proteins are isolated from the tumour cells and reduced to peptides with the aid of enzymes. Subsequently, researchers identified the proteins from different samples with a mass spectrometer and compared the quantities in the analysed samples.

The researchers thus examined ten samples taken from tumours that formed in the liver and ten from tumours that migrated from the pancreas to the liver. They successfully identified and quantified approximately 2,000 proteins. Then, they compared which type of tumour results in the formation of which proteins. The important thing was to identify those proteins that occur in larger quantities in one type of tumour, but not in other types of tumours.

Three promising candidates

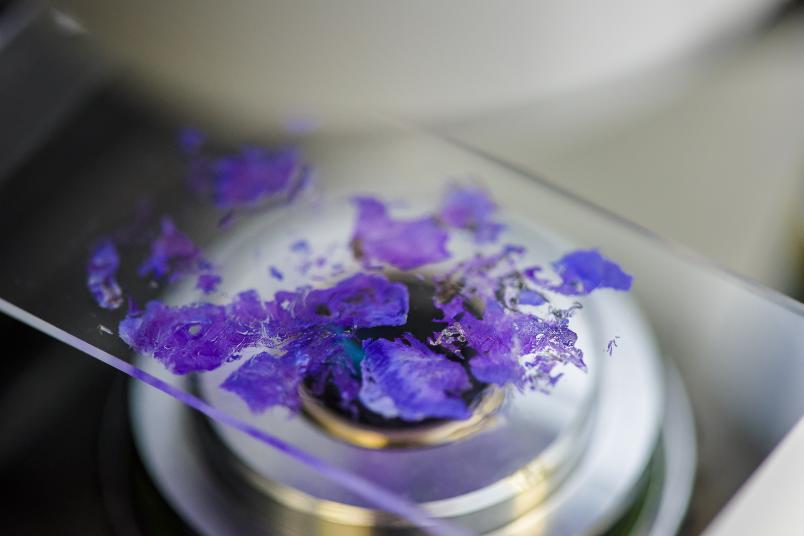

In the following stages, the researchers studied three particularly promising candidates from the family of annexin proteins, namely ANXA 1, ANXA 10 and ANXA 13. Using immunohistochemistry, the proteins taken from samples of both types of tumours were stained. This can be done with specific antibodies that react with the proteins in the tissue, thus creating stains. Under the microscope, the researchers can then see if and which areas of the tumour sample look stained.

This method enabled the researchers to demonstrate that ANXA 1 and ANXA 10 can be detected in larger quantities in liver tumours and in significantly smaller quantities in pancreas tumours. Whereas it is exactly the other way round for ANXA 13.

For the purpose of diagnostic distinction between the types of tumours, it is important if that difference can also be demonstrated between primary liver tumours and the metastases of pancreas tumours. “We carried out initial analyses of primary tumours from both organs, because metastases were available only as paraffin-embedded tissue. For the purpose of proteome analysis, however, we require freshly frozen material,” explains Barbara Sitek. When comparing the three proteins taken from liver tumours and from metastases of pancreas tumours, it emerged that ANXA 1 and ANXA 10 were the only ones where different staining patterns could be detected. Consequently, ANXA 13 was excluded.

In the next step, the remaining two candidates were analysed with regard to how sensitive they are and how specifically they point to one of the diseases. They boasted a reliability of 80 per cent each. “This is quite good, but it means that some 20 per cent of the diagnoses are still wrong,” elaborates Barbara Sitek. Therefore, the research group used the proteins in combination, but that did not result in a higher accuracy, either.

Already, patients are benefiting from our work.

Hideo Baba

In order to ensure reliable diagnoses, the researchers then tried combining the detected biomarkers with eleven other proteins, which had been suggested as potential biomarkers in publications by other researchers based on older studies. Combining ANXA 10 with a protein put forward in specialist literature, they achieved an accuracy of 85 per cent. “This is a good value that considerably improves the differential diagnosis for liver tumours,” says pathologist Hideo Baba. “Already, patients are benefiting from our work, which was only possible thanks to the collaborative effort between the Proteom-Center in Bochum and the university clinic in Essen,” says the researcher. At the Institute of Pathology at the university clinic in Essen, these biomarkers are already being used in routine diagnoses.

The researchers from Bochum and Essen deploy their method for searching reliable biomarkers that they tested in the course of the project for other diseases, too.