Archaeology

Buried in salt for centuries

Several salt mummies have been unearthed in an old mine in Iran. Some of them originated before the birth of Christ. Who were they? And how had they lived?

In 1993, miners in the north-western part of Iran made an accidental discovery that brought about a number of spectacular finds. In salt mines near the village of Hamzehlu in the Chehrābād region, they found parts of a body that were exceedingly well-preserved, as they had been stored in salt. In 2004, the remains of a second body surfaced. A year later, two other salt mummies came to light, following an emergency dig commissioned by the Antiquities Authority. To date, body parts of eight individuals have been recovered, which have been preserved in salt over centuries, complete with skin, hair, organs and even the clothes they wore. The circumstances of their death and the culture in which they lived are being analysed in an international research project coordinated by Professor Thomas Stöllner at Ruhr-Universität Bochum, which has been co-funded by the German Research Foundation since 2010.

Thomas Stöllner is expert on the archaeology of salt mines and has been conducting research in Iran for 17 years; having frequently been on location himself, he has learned to speak the local language. “After the Iran–Iraq War, RUB and Deutsches Bergbau-Museum were among the first institutions that carried out archaeological research in Iran,” points out Stöllner. He has been involved in the Chehrābād project since 2005. After the region has been declared a conservation area, extensive excavations have been taking place there.

Mine rises to the surface

In a place where rock salt was mined well into the 21st century, a mine had existed as far back as 700 BC, which was continuously in operation until 400 AD. “The Iranian salt mine in Douzlākh opens up unique opportunities to expand our understanding,” explains Thomas Stöllner. “Unlike on other sites, parts of the old mine can be accessed from above.” Following geological shifts, the salt deposit itself tilted upwards and could therefore be mined on the surface. Modern surface mining methods destroyed the surface layers that are rich in salt, as well as several areas of the old mine; on the other hand, it paved the way for the mummy finds and rendered parts of the old structures accessible from above.

Favourable conditions

“In other locations where we research old salt mines, for example in Austria, we have to dig tunnels below ground and search for archaeological finds there,” as Stöllner describes the usually adverse conditions. “This is not only more difficult, but it also takes longer to bring individual finds together and understand the connections between them.” In Chehrābād, the project team has used excavators to dig a profile with a length of 60 metres and a height of 35 meters. This wall provides a cross-section of all excavation layers. “In Austria, it took us 20 years to do the same thing,” explains the archaeologist from Bochum. “In Iran, we excavated the profile in the course of three campaigns that took a few weeks each – sometimes with the aid of machines.”

In addition to mummies, the researchers also unearthed many well-preserved clothes, pots – some of them still containing food residue – and wooden tools. According to official count, six bodies have been retrieved from the old mine to date; but the researchers have estimated that the finds contain parts of two other bodies.

Disaster at excavation site can be explained

Three of the bodies discovered so far date back to the Achaemenid Empire, i.e. the time of the First Persian Empire that stretched from the 6th century to the late 4th century BC. The most spectacular find according to Thomas Stöllner is the so-called Mummy No. 4: a boy between 15 and 16 years of age who was a worker in the mine. Between 405 and 380 BC – as reconstructed by the researchers from Bochum in collaboration with colleagues from Oxford with the aid of radiocarbon dating – parts of the mine collapsed, possibly due to an earthquake. At least two more people died during the disaster. “At our excavation site, we are pretty much in the spot where the disaster took place,” says Thomas Stöllner. “We can see the salt blocks that dropped on the boy and killed him. We know that there is a second person, who is still wearing their rucksack, who ran away and was likewise killed by falling rocks. As far as the third person is concerned, the location of the find is unfortunately less clear, because it was excavated back in 2004 during regular salt mining operations and without any archaeological examinations.”

It’s as if they’d died yesterday.

Thomas Stöllner

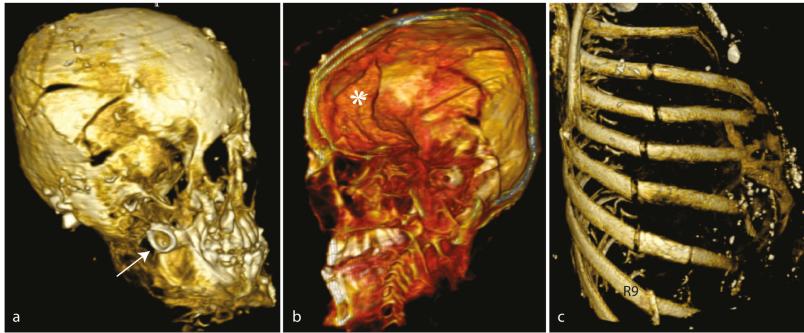

Stored in salt, the bodies have shrunk a bit, but all organs have been preserved. “It’s as if they’d died yesterday,” explains Stöllner. Based on three-dimensional tomographic scans taken in a hospital in Teheran, the researchers from Zürich reconstructed the inside of the body in the course of the project. The images showed, for example, fractures to the young worker’s skull and thorax and his lacerated interior organs.

By now, the project team has found out much more about the boy who died in the mine. “We know that he was a well-nourished young man, probably from Central Asia or from the Caspian Sea,” says Stöllner. The researchers, in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Oxford, have been determining the origins using isotopic analyses. Isotopes are variants of a chemical element which differ in neutron number in the nucleus and vary in weight. Certain isotopes of oxygen and nitrogen indicate a person’s diet, which can be indicative of a specific region of the world – in the boy’s case, it is typical of the Caspian Sea or Central Asia.

As Thomas Stöllner says, it is not surprising that people from different regions worked in the mine. “The Achaemenid Empire was huge. We know from written sources that there were interrelationships among all parts of the Empire as well as a high level of mobility – just like in the EU today,” explains the archaeologist.

Three disasters in the mine

The disaster that killed the boy was not the only one that occurred in the Douzlākh mine. There must have been at least three cave-ins: the second one approximately 300 BC, and another one between the 5th and 6th century BC.

To determine the era, the researchers use radiocarbon dating. It is based on the instable isotope of carbon, namely 14C that continuously decreases in dead matter. Broadly speaking, the volume of 14C can thus be used to calculate the age of a mummy or of a wooden item.

Mine and environment had an impact on each other

The team was not only interested in the events in the mine itself, but also in the life surrounding it, as they appeared to have had an impact on each other. Even in the early stages of the Achaemenid Empire, a vast agricultural system evolved in the area surrounding the mine, which was subsequently considerably optimised during the Sasanian Empire, presumably because an irrigation system was implemented. This is because one of the region’s problems was that drinking water was scarce due to the high salt content.

“Presumably, humans were initially unable to settle in the region,” speculates Thomas Stöllner. Thanks to the profits yielded by the salt mine, the inhabitants might have eventually been able to set up an irrigation system – according to one theory. Consequently, this paved the way to a rather more stable agriculture and settlement. This, in turn, meant that the mine could be exploited more efficiently because of a higher number of labourers on location. “However,” points out Stöllner, “possible interpretations should always be handled with caution. In spite of the excellent conditions in Iran, we only see snippets of history, which we then have to tie together using our own hypotheses.”