Medicine

Big Data against hepatitis

An extremely fast reproducing virus is to blame for the therapy resistance of hepatitis E virus. Still, it has now helped researchers creating a cell culture model.

As far as research is concerned, hepatitis E virus (HEV) had long led a shadowy existence – even though it is the main cause for acute viral inflammation of the liver. In healthy humans, the infection is often symptomless and doesn’t result in any negative long-term effects; for individuals with a weak or compromised immune system, however, hepatitis E virus may pose a real threat. “Organ recipients and HIV patients, for example, are two at-risk groups for chronic hepatitis E virus infection, which can be quite severe,” says Dr. Daniel Todt from the Department for Molecular and Medical Virology at the RUB Faculty of Medicine. Approximately 70,000 patients die from hepatitis E each year.

Unlike with other viruses, there is no vaccination available for hepatitis E virus, nor do any specific effective drugs exist. Some – but not all – patients respond to active substances commonly used against viruses, such as interferon alpha and ribavirin. “If those treatments fail, however, there is no alternative at present,” says Todt.

Why is the virus so mutable?

Researchers don’t know enough about the virus to develop effective therapies. How exactly does it replicate? What makes it so mutable? Why doesn’t it always respond to treatment with common drugs? Striving to find the answers to these questions, Daniel Todt and Professor Eike Steinmann collected and analysed serum samples from patients with chronic HEV infection over a one-year period. The group included both patients who responded to ribavirin treatment and patients in whom the therapy failed.

The researchers were primarily interested in the genetic information of the virus, as that is the key to its adaptability. HEV carries its genetic code in the form of a single RNA strand composed of approximately 7,200 units, the nucleotides. The RNA contains the blueprint of a polymerase that aids the replication of genetic information. It is error-prone and, unlike for example mammalian polymerases, it doesn’t have a proof-reading activity for error correction. “This means that the process of replicating genetic information results in countless genetic variants of the same virus,” elaborates Eike Steinmann. “A viral population thus forms in the host.”

The researcher analysed the genetic code of those viral populations by performing so-called deep sequencing at different points of time. This relatively novel method is deployed to represent the genetic information of all viruses in a sample as comprehensively as possible. “Whereas in the past, scientists only analysed the genetic information of those virus particles that occurred most frequently,” explains Daniel Todt.

One genetic variant attracted particular attention

Using deep sequencing, the researchers were able to determine which virus variants were present in the population in which quantities, and how they are changed over time. Ribavirin therapy in particular yielded interesting results, as the researchers explain:

Once the tests had been evaluated, it emerged that the virus populations in chronic HEV patients were particularly diverse. Certain genetic variants accumulated in patients who did not respond to ribavirin therapy. “Interestingly enough, those variants were often present before therapy commenced, but their numbers were quite low at first,” describes Daniel Todt. “Over time, they would become the dominant variant within the population.”

One genetic variant caught the researchers’ eye: it promoted the proliferation of the virus to a great extent – a happy coincidence for the virus. Due to the speedy replication, that variant quickly became dominant within the population and caused a drastic increase in virus quantities. “Ribavirin thus became ineffective, which in turn probably led to resistance being built,” explains Daniel Todt.

These findings have enabled the researchers to predict the outcome of ribavirin treatment in individual patients at an early stage. “To this end, we have to examine the genetic information present in the virus population at the outset of therapy and monitor its development,” says Daniel Todt, who has been awarded several prizes for his research.

Usually, medicine is said to progress from bench to bedside – in this case, the path has been reversed.

Daniel Todt

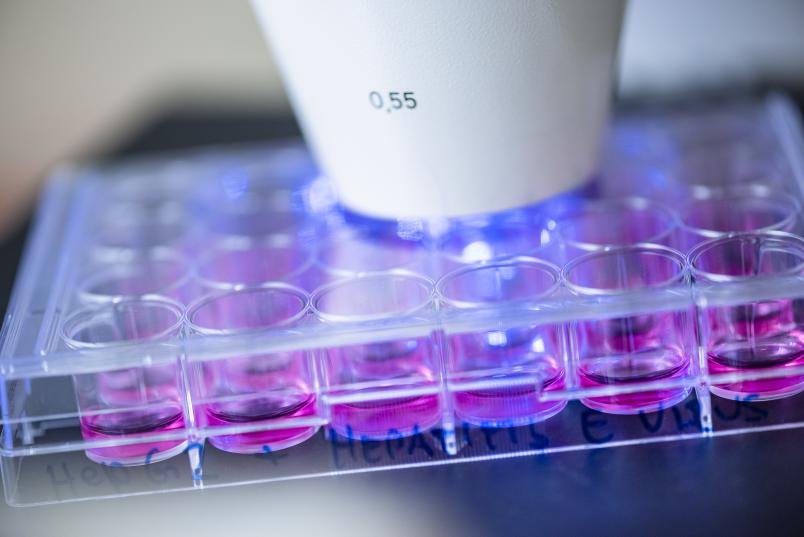

For the researchers in Bochum, discovering of the extremely fast reproducing virus variant was a stroke of luck in yet another respect. They were thus able to establish a cell culture system for hepatitis E virus. “To date, it had not been possible to proliferate viruses in a culture sufficiently; consequently, the measurement window for analysing hepatitis E virus in cell culture was much too small,” points out Eike Steinmann.

Therefore, the researchers cloned the genetic information of the variant they had discovered in a HEV cell culture system, which they can now use in order to, for example, test the efficacy of drugs against hepatitis E viruses. “Usually, medicine is said to progress from bench to bedside, meaning from the lab to the treatment of patients – in this case, the path has been reversed,” says Daniel Todt. “The findings we made when analysing samples taken from patients have facilitated our work in the lab. We are hoping to publish these results in the near future.”

A first variant of the cell culture model was utilised to test how the naturally occurring active substance silvestrol affected the replication of hepatitis E viruses. Silvestrol is formed by approximately 400 different mahogany plants and can be extracted from their leaves. It has been put forward as a substance that may potentially be used to treat certain tumours and Ebola, but it has not been used in clinical applications as yet.

In order to determine how silvestrol affects hepatitis E viruses, the Bochum-based researchers spearheaded an international team. They treated so-called reporter viruses in cell cultures with silvestrol and found that the viruses replicated less than without the treatment.

With Silvestrol, the multiplication rate dropped drastically

In the next step, the researchers used primary stem cells that they had differentiated into liver cells. They infected them with hepatitis E viruses – both those they had previously produced in the laboratory and those that came from patients and had been purified. The researchers observed the course of infection with and without silvestrol for several days.

Following treatment with silvestrol, the multiplication rate and the number of infected cells dropped drastically. “The effect of silvestrol was stronger than that of ribavirin,” explains Daniel Todt.

In order to investigate whether the active substance also inhibits viral replication in living organisms, they tested its effect in mice that were implanted with human liver cells and infected with hepatitis E. Here, too, the treatment with silvestrol led to less replication of the viruses.

These results raise hopes that silvestrol might be an effective treatment for hepatitis E. “The clinical potential must be explored in further studies,” says Eike Steinmann. “Our research is laying the foundations for this.”