A day with the biopsychologists

Visiting the masterminds of the avian kingdom

Corvids are incredibly clever. But they are not always the easiest birds to handle.

Eight pairs of eyes are regarding me curiously. Alert, yet fairly sceptical. Huddled together and keeping their distance, the jackdaws remain sitting on their perch, quite still. “It’s not always like this,” says Dr. Jonas Rose. “When the PhD researcher who works with them comes in, the birds squabble who’s allowed to perch on her arm.” The biopsychologist has been researching corvids for many years and he knows that they don’t appreciate new things at all. That includes new visitors like myself. Still, today I am permitted to watch the jackdaws learn a new complex task, namely memorising a sequence of locations that they visited and the colours they saw there. A difficult test for the working memory that serves as short-term information storage in humans and in animals.

All it takes is wearing the wrong t-shirt and the bird may refuse to come to work.

Jonas Rose

Athene and Kramurx have been training in a special aviary at RUB, the so-called arena, for a year. And the researchers really need the wild birds to be cooperative. In order to habituate them to humans, they raise them by hand from chickhood and spend a lot of time with them. Every small detail counts. “All it takes is wearing the wrong t-shirt and the bird may refuse to come to work,” explains Rose and admits that it’s not always the researchers training the birds; sometimes it’s the other way round. “We used to have a crow in our group who would only participate in an experiment if the PhD researcher held their hand into the experiment space,” he remembers.

Extremely intelligent

Without fail, I am reminded of toddlers who have their parents wrapped around their finger. You might wonder why the researchers put themselves through the trouble of working with the eccentric corvids. The reason is quite simple: they are highly intelligent – despite the fact that they are far removed from humans in evolutionary terms. Jonas Rose and his team intend to find out how their brain performs such feats and what it has in common with mammals.

His research group is one of two worldwide that conduct this kind of research with corvids. In the recent years, other groups have already demonstrated that the animals are capable of showing outstanding cognitive performance.

Capabilities resemble those of humans

Many researchers believed for a long time that humans are the only species possessing an episodic memory – that means remembering individual events, for example what they had for dinner at a restaurant last night. Various experiments have shown that corvids too are able to remember what they did where and when, and that they are even capable to planning for the future.

It has not yet been understood how their brain manages to do all that. After all, its structure is completely different than that of the human brain. The arena experiment conducted by the RUB research group Avian Cognitive Neuroscience is supposed to shed light on the relevant neural basis. It does not study the episodic memory directly, i.e. the memory of unique events, but the basis thereof: namely how birds store what they did where and when in their short-term working memory.

Finding the neural basis

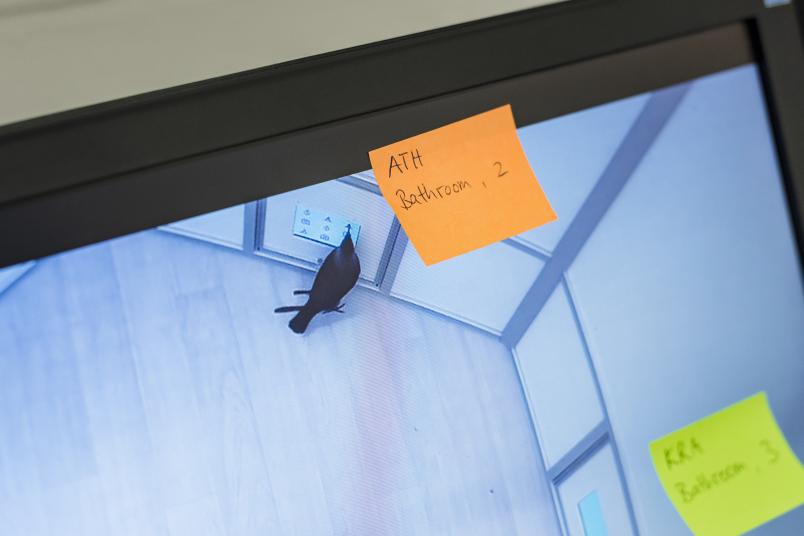

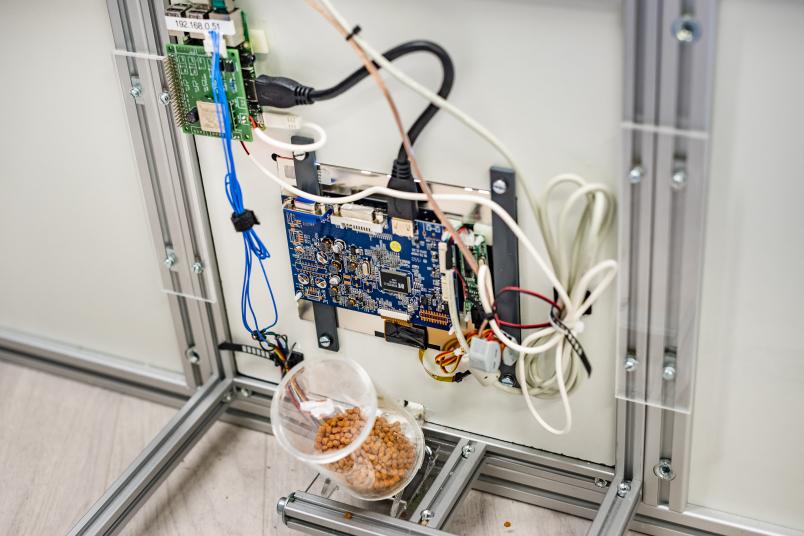

We enter the lab where a hexagonal aviary has been set up that is fitted out with a touchscreen on each interior wall just above the ground. PhD researcher Aylin Klarer demonstrates the experiment. She climbs into the arena and places small cheat sheets in front of three touchscreens. They say “port”, “camping site” and “bathroom”.

A blue dot flashes on the port touchscreen, the researcher taps it a few times and then quickly looks around to check where the next dot appears. At the camping site. She taps it, turns to the third dot at the bathroom, and taps it – all this while crouching, as the experiment is laid out to take place at the birds’ eye level. A fourth monitor displays a random sequence of the three symbols: port, camping site, and bathroom. They have to be tapped following the same order in which the dots previously appeared in the three locations. Aylin Klarer gets it right; a flap opens and releases some seed balls.

Cheat sheet only for humans

Using the cheat sheets, we can keep track of where the camping site, the bathroom and the port are. But how do the birds do it? All sides of the arena look exactly the same. How do they know which touchscreen is located at the port and which one at the camping site? “The birds have learned how the symbols are assigned to the locations through association,” explains Jonas Rose. At first, they picked at the symbols at random; but only if they got the sequence right, they were rewarded with food. “It took only one month to teach them all this, they’re really good at it,” continues the researcher. Athene and Kramurx train for two hours every day.

Now, the test has become much more complicated. A circle in different colours – blue, red or green – flashes at each of the three locations. The jackdaws must remember which colour they saw at which location and in which order. The allocation of colours to the locations and the sequence of the locations change in each round of the experiment.

Colours more difficult than locations

Aylin Klarer is still crouching in the arena. She’s demonstrating an experiment round with location and colour. Red, blue, green. That was the sequence. But did it start at the port or at the camping site? Tricky! Without our cheat sheet we’d be lost. And the birds? “If all they have to do is name the location sequence, they get it right in 60 to 80 per cent of all experiment rounds. They still have trouble with the colours,” says Jonas Rose. “We have recently adjusted the experiment design in order to figure out the reason for that.” Is it just because the birds’ working memory can’t handle so much information at the same time? Or have the researchers simply not found the right training strategy yet? This is to be determined in the next few weeks.

Our intention was to try out the most ambitious thing we could think of first.

Jonas Rose

The biopsychologists could certainly simplify the experiment. “But our intention was to try out the most ambitious thing we could think of first,” points out Jonas Rose. His studies are financed through the Collaborative Research Centre 874 and a Freigeist Fellowship of the Volkswagen Foundation that has been specifically established to fund research projects that break new ground and the outcome of which is uncertain.

Rose still expects that the animals are going to learn the more complicated task. Athene at least is making progress, whereas Kramurx appears to be only memorising the location and ignoring the colour. “These birds are clever. Kramurx knows that he’s getting enough food with his strategy and doesn’t have to go hungry,” says Rose. “When performing highly sophisticated cognitive experiments, the cheaper solution is often the more attractive one.”

Irresistible mealworms

Aylin Klarer has now fetched one of the jackdaws for their daily training in the lab. Despite the wintry temperatures, the PhD researcher has taken off her cardigan. “Athene only knows me wearing a shirt,” she explains. Right, changes are not welcome. While the jackdaw is sitting on its perch, I am allowed to approach it cautiously. I stretch out my hand with a few mealworms and seed balls. Athene hesitates, looks around frantically. For a moment, I’m worried she’s going to turn her back on the treats; but then she goes for them after all. “She’s unable to resist a yummy worm,” says Klarer.

Then, it’s time to do some work. Aylin Klarer puts the jackdaw down in the arena, closes the door and starts the experiment. A video of what the bird is doing is transmitted in real time and we can watch it on a monitor. Athene is waiting, hopping around rather irritated. “We should leave,” says the PhD researcher. “She’s used to being left in peace when she’s in the lab.” We’re leaving. We can watch what’s going in the office just as well. By the time we get there, Athene is already hard at work. She’s hopping eagerly from monitor to monitor, picking at the dots, and it looks like she can barely wait to answer the puzzles. The first rounds go wrong. I worry that Athene may be still confused due to the stranger visiting her. In that moment, the flap opens and the seed balls roll out. The correct answer. That’s a relief.