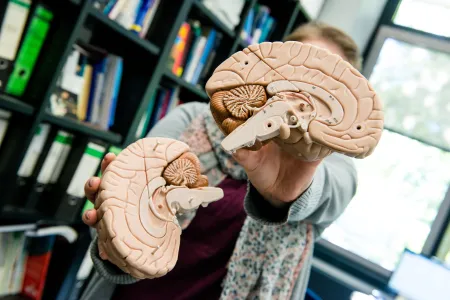

Neuroscience

How memory sharpens perception

A computer model provides new insight into the function of a brain region that is important for long-term memory.

A group of computational neuroscientists from RUB showed with the help of a computer model that the medial temporal lobe could be indirectly involved in perception processes. This brain region has so far been known to be involved in long-term memory. The results were published in the journal Hippocampus, online on 30 December 2019.

Different brain structures within the medial temporal lobe (MTL) ensure that we can consciously remember facts and experiences. However, a number of studies suggested that the MTL is also involved in perceptual processes. Patients with a brain lesion in the MTL do not only have problems with memory, but also with perceptually differentiating between objects.

Some neuroscientists see these results as an indication that the MTL could be involved in the processing of visual information. Other researchers only conclude from the results that the assigned tasks also require memory and therefore the patients with the limited memory capacity performed less well.

Computer algorithm with a memory

With a computer model, RUB reseachers Professor Sen Cheng, Professor Laurenz Wiskott and Richard Görler have contributed new insights into the function of the MTL. Their theory: sensory representations – and thus the ability to interpret sensory impressions – are initially learned through the processing of sensory perceptions, but they can be improved down the line by replaying experiences from memory.

To test this theory, the researchers had a computer algorithm – slow feature analysis – perform a visual discrimination task. First, the algorithm had to learn to recognize two different images; it created visual representations of the two images. One showed the letter T and one the letter L. When creating the visual representations, the algorithm had a kind of memory available in one part of the experiment but not in the second part.

Better with memory

Afterwards, the algorithm with memory and the algorithm without memory had to face the visual discrimination task, where they should tell whether different images were more like the letter T or L. The letters were presented with background noise. They also overlapped each other. “The algorithm works better the less attention it pays to the background noise,” explains Richard Görler, first author of the study.

The researchers found that the algorithm that could create the visual representation of the letters with the help of a memory performed better in the discrimination task than the algorithm that was trained without memories. To the RUB researchers, this result means that the medial temporal lobe does not have a direct role in the processing of sensory information, but because of its function in memory it helps to ensure that sensory perceptions can be interpreted more accurately.

Funding