Interview

“Models and reality don’t match”

So far, there is a lack of long-term models that depict absolute poverty in developing countries and effective measures to fight poverty in a sustainable way. The EU-funded joint project ADAPTED hopes to change that.

According to Professor Wilhelm Löwenstein, there are still not enough answers to the two questions of how poverty can be explained and reduced in the long term. In an interview, the director of the RUB Institute of Development Research and Development Policy (IEE) and professor for development research at the Department of Management and Economics at RUB, outlines how the team of the European joint project “ADAPTED” is seeking new answers. He initiated the project together with several European partners, the RUB legal scholar Professor Markus Kaltenborn and the IEE managing director Dr. Gabriele Bäcker. ADAPTED is a European Joint Doctorate, a specialised research training group in which international doctoral students work together with European teams of supervisors in the search for economic models, political solutions and better legal frameworks to combat poverty.

Professor Löwenstein, the global reduction of extreme poverty is the first of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals that the United Nations wants to achieve by 2030. What does the UN mean by extreme or absolute poverty?

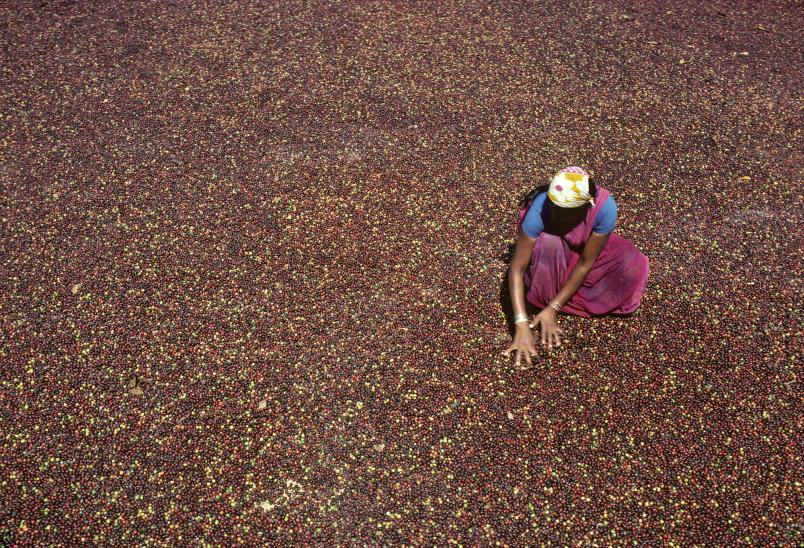

The World Bank and the UN system define absolute poverty using a basket of goods that represents the minimum daily needs of a person in terms of basic food, clothing and shelter per person per day. It marks the poverty line. To cover these minimum needs, a person in Manhattan has to spend 1.90 dollars per day at the prices applicable there; in Lilongwe, the capital of Malawi in Southeast Africa, a person needs 0.64 dollars per day to finance the same basket of goods – due to the differences in purchasing power. Accordingly, anyone who can’t spend 1.90 dollars a day in the USA and 0.64 in Malawi is considered absolutely poor. This form of poverty, which manifests itself in hunger, malnutrition, lack of access to clean water, medical care and education, affects an estimated two-thirds of the population in Malawi and almost half a billion people in sub-Saharan Africa.

[einzelbild: 1]

Does this form of extreme poverty also exist in Europe?

No. In Europe, we don’t have absolute poverty. When we refer to poverty here, it’s about assessing people as being at risk of poverty because they earn less than the average. Our statistics show, for example, that in 2019 just under 16 per cent of the population in Germany were at risk of poverty, living on less than 60 per cent of the median income of the population as a whole. For a one-person household, this translates into a relative poverty line of 14,109 euros per year or 38 euros per day. Anyone with less is considered to be at risk of poverty. And there you can see the huge difference to the absolute poverty line set by the UN. Absolute poverty, which we research as part of the European Joint Doctorate and which the UN refers to in the Sustainable Development Goals, has absolutely nothing to do with relative poverty, which we measure in Europe.

[infobox: 1]

How can absolute poverty be mapped and explained in scientific terms?

Poverty is volatile, but there are trends. For example, in China we have been observing a sharp decline of poverty rates since the 1980s. Although the population has grown in recent decades, the proportion of those living below the poverty line has fallen from an initial 90 per cent to ten per cent – a huge success. Poverty is a long-term phenomenon that we can assume is closely linked to long-term growth trends. To explain them, economists have been presenting a series of ever-improving growth models over time.

How can absolute poverty be described with these growth models?

It can’t, because these growth models were designed to describe and explain productivity and income growth in industrialised countries. But in these countries absolute poverty doesn’t exist. The theory assumes that, despite existing differences, all people in an economy work under similar conditions and that economic growth is the result of investment and technical progress. Both lead to productivity growth, rising wages, and rising living standards for everyone. If our conventional models were also applicable to developing countries, the incomes of the poorest of the poor would have to increase through growth, and absolute poverty would have to disappear. But the incomes of the poorest don’t increase systematically anywhere. However, we do observe that in some developing countries the percentage of the population living in absolute poverty is decreasing, in others it’s stagnating and in still others it’s increasing, and this can’t be explained by the existing growth models.

Why not? Where’s the fallacy?

If you apply the existing models to developing countries, you implicitly assume that their economies are lagging versions of the industrialised economies, but that they function very similarly at the core. Consequently, a country like Malawi would only need to invest more in machinery and equipment, in education and health, enable technological progress and improve its institutions, and absolute poverty would soon be history. The data suggest, however, that it’s not as simple. It seems that in reality, the similarity of economies is not as large as the traditional models assume.

Why is that?

Let’s continue with Malawi as an example: There are banks that are just as up-to-date as our Sparkasse in Bochum, farms that are similar to those in Brandenburg, and industrial mining that is organised in the same way as ours. In Malawi, too, people employed in such businesses work with modern machines and benefit from the technical progress. They have work contracts, are productive, are paid a reasonable wage and live above the poverty line. Unlike in high-income countries, however, a large part of the labour force in Malawi works in the informal sector, for example in subsistence agriculture, as day labourers or as street vendors. These forms of employment no longer exist here. They are reminiscent of economic activity in Europe 150 or more years ago. Here, production is essentially done without machines, without technical progress and with the use of human labour; labour contracts don’t exist, productivity is low, and therefore workers in the informal sector earn incomes below the poverty line. Our approach in the ADAPTED project takes into account the existence of such structural differences between the modern and the informal sector.

What does this mean in practice?

Our growth models include informality and poverty. Investments and technical progress then only apply to the modern sector. The latter expands and increases the number of workers it recruits from the informal sector because it pays higher wages. The workers in question and their families escape absolute poverty. However, growth changes nothing for all those workers who remain in the informal sector. They continue to live in absolute poverty. Moreover, we show that high growth contributes only imperceptibly to poverty reduction in countries that have a small modern sector and, therefore, high poverty rates. And that means that a consistent growth policy is not enough to fight absolute poverty, especially in poor countries. It needs more than that.

How does this affect government measures to combat poverty? Do tools like the minimum wage or social security systems prove helpful in developing countries?

In developing countries, the poorest of the poor don’t benefit from the introduction of a minimum wage or of social security systems. A minimum wage increases neither the turnover of the informal street vendor nor the income of the subsistence farmer. And neither of them has access to social security, because they can’t afford to pay social security contributions, which is a requirement for receiving social benefits in developing countries.

Which measures do reach the absolute poor in developing countries?

In the short term, there is only one thing that helps when a person is absolutely poor: higher income. Donors like the World Bank or the European Union routinely provide countries with funds to subsidise the poorest of the poor. And again, a lot of questions arise: How do we organise and manage such cash transfers on behalf of the governments? How can resources available in developing countries be mobilised to support their poorest citizens? How do we reach those who need support the most? We try to find answers to these questions within the ADAPTED project.

[einzelbild: 2]

What is ADAPTED researching in detail?

This project aims to contribute to an improved understanding of poverty trends and the effectiveness of measures to combat absolute poverty. Combining perspectives from the fields of economics, law and governance research, the premise of our work is the existence of the informal poverty sector. We approach our goals in three multidisciplinary research groups, each working both theoretically and empirically. Developing countries not only differ from industrialised countries, but they also differ significantly from each other. The first research group studies the effects of individual growth and social policy approaches on absolute poverty, taking these national differences into account. Poverty reduction measures are not implemented in a policy vacuum, but are embedded in a multitude of other policy projects and programmes. Therefore, the second research group examines the interactions that exist between poverty-reducing and growth-promoting programmes on the one hand, and analyses, on the other hand, how measures in other policy areas – for example climate protection – affect the effectiveness of poverty-oriented policies. There are individual examples of good coordination of pro-poor policies and functioning poverty reduction programmes in developing countries. The third working group explores the question of which legal and political mechanisms contribute to producing such good results.

How is the ADAPTED graduate programme structured?

Among 300 international applicants, we have selected 15 high-performing and committed PhD students with a background in social sciences, who took up their European Joint Doctorate in September 2021. They are each mentored and supervised by an international two-person team recruited from the five participating universities in Germany, the Netherlands, France and Turkey. All five university partners organise a joint programme that specifically supports early career researchers during all doctoral phases. The 15 doctoral students work together across locations in our three multidisciplinary research groups, conduct field research in Africa, gain international teaching experience, perform hands-on work at non-university partner institutions and will eventually receive doctoral degrees from two European universities upon successful completion. This results in impressive competence profiles that prepare students for a job in research, in international development cooperation or in internationally operating enterprises.

And (how) will the research continue after three years of ADAPTED?

I’m quite confident that we will present a great number of interesting results in the course of these three years. At the same time, we’ll unearth new questions, based on which the international ADAPTED team will continue to work together in the future.

[infobox: 2]

[infobox: 3]