Colonial history

Insights into the life and mindset of a genocidal murderer

Today, it is undisputed that German troops committed genocide in South West Africa during the colonial era. An editorial project reveals the perspective of a perpetrator – and a prominent perpetrator at that.

It’s nothing more than five inconspicuous notebooks from the beginning of the 20th century. But they have explosive potential. For a long time, they were privately owned, not accessible to the public at all and to researchers only to a limited extent. Recently, Namibian victims’ associations demanded their release. Now, RUB historians Dr. Andreas Eckl and Dr. Dr. Matthias Häussler have been given the opportunity to edit them. The author of the diaries is none other than Lothar von Trotha – the man responsible for one of the worst crimes at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1904 and 1905, he was the commander-in-chief of the so-called Schutztruppen in the colony of German Southwest Africa, today’s Namibia. There, he was in command when the genocide of tens of thousands of OvaHerero was committed.

The genocide of the OvaHerero

“It was the inglorious climax of German colonial history,” says Andreas Eckl. “Today, there is a great political need to confront this chapter.” The sources, however, are scarce. This is because the files of the Schutztruppen in German Southwest Africa haven’t been preserved: The originals were destroyed in the First World War, the copies in the Second World War. “We’ve known for many decades that diaries of the commander-in-chief Lothar von Trotha do exist,” as Matthias Häussler tells us. “Everyone wanted to know what they said. But they were not readily accessible.” The diaries were the private property of the von Trotha family.

Controversial project initially rejected

Häussler was in contact with the von Trotha estate for years. “It took some patience to get permission for us to edit the books,” he recalls. “Even though the family was fairly open to the idea early on.” Funded by the German Research Foundation, he’s been working on this edition at the RUB Institute for Diaspora and Genocide Studies together with Andreas Eckl since the beginning of 2021. The German Research Foundation had initially rejected the controversial project, but then approved it subject to conditions after the von Trotha family had guaranteed cooperation in writing.

I believe the German Research Foundation imposes these conditions for our protection.

Andreas Eckl

The researchers are allowed to edit the diaries with a critical commentary, i.e. they are allowed to publish them with contextual annotations. However, they are not allowed to make any reference to the general academic discussion, i.e. they are not allowed to evaluate the content. In addition, they have to publish the original writings as well. “I believe the German Research Foundation imposes these conditions for our protection,” Eckl explains. “RUB shouldn’t have the sole prerogative of interpretation, so that we don’t make ourselves vulnerable to attack.”

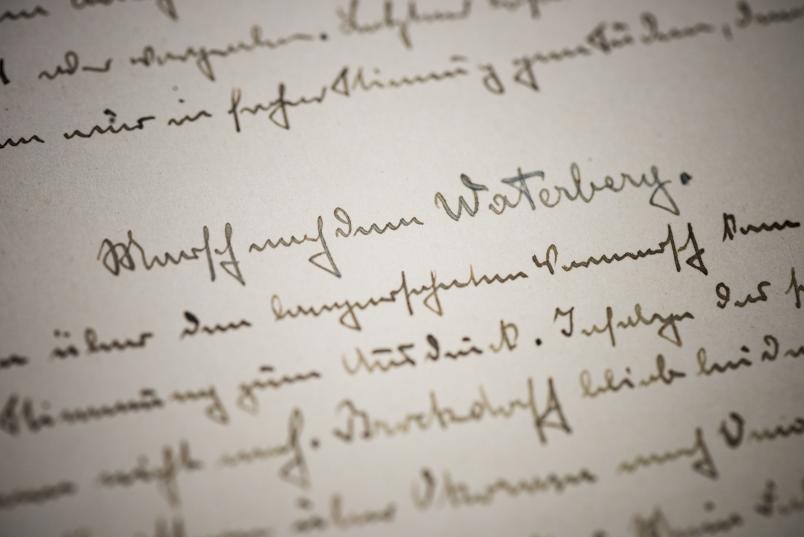

800 pages – some written on horseback

The notebooks contain a total of 800 pages. “The originals are in surprisingly good condition, considering that they weren’t stored in an archive,” says Häussler. Even so, deciphering them was a challenge. “Lothar von Trotha wrote some of his notes in specific locations like Windhoek or on board a ship. But some of them, he wrote on the march and on horseback – and this is exactly what they look like,” he explains. “By today, we have cracked 99.8 per cent of the text,” adds Häussler. “Working on the dairies, we’ve become accustomed to the typeface over time, and it took us less and less time to get it right.”

The historians have been clear about one thing from the outset: the diaries are of no relevance in assessing whether the colonial troops in German South-West Africa committed genocide or not. “There’s no doubt whatsoever that they did,” says Andreas Eckl “It was genocide. And the diaries don’t contradict it at all.” Historians hope to use the journals to learn more about the circumstances leading up to the genocide, about motivations for action, details of warfare, command structures and the question of whether it was a genocide planned long in advance or a process of escalation.

Documenting the details of each day

According to Eckl and Häussler, the diaries show a commander-in-chief who was very full of himself and who enjoyed the privileges that came with his high-profile rank. Although it does contain some personal information, the text is predominantly matter-of-fact, as is illustrated by the following example: Lothar von Trotha’s wife died while he was on active service. However, the author only mentioned this loss in a few words. In contrast, he describes in detail the attentions he received – such as flags at half-mast and telegrams of condolence from the Kaiser and the Reich Chancellor.

“Still, it’s astonishing what he didn’t write down,” says Häussler. For example, many routines of command are not described. “Trotha always records the particular details of each day. This is typical of the diaries, for example, a situation when persons introduced themselves for the first time, an argument took place or a special meal was served,” illustrates the researcher. “He used the diary as a way of keeping track of extraordinary occurrences in his everyday life.”

According to Andreas Eckl, Trotha’s notes also cast new light on the man himself: “He was not just the butcher he’s always portrayed as,” says the researcher. “He was that too, but there was more to him than that.”

Second source: Trotha’s photo album

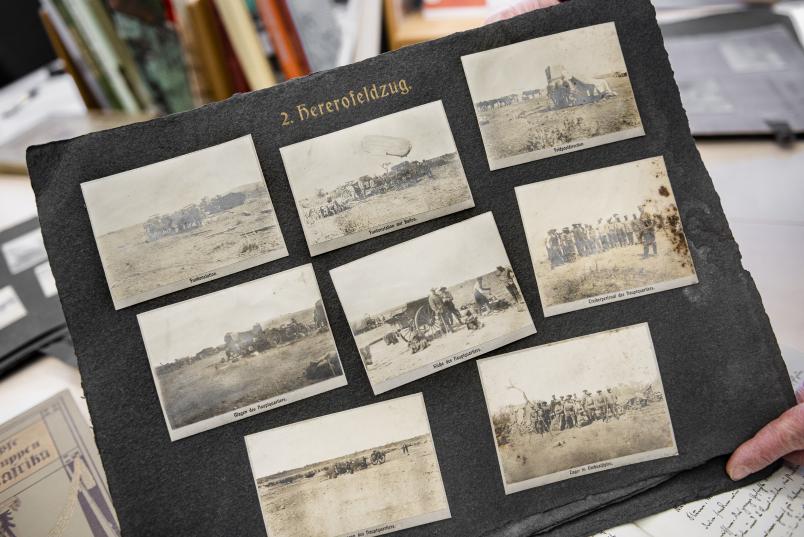

The Bochum-based researchers supplement their annotated edition of the diaries with another important source: a photo album that Lothar von Trotha compiled after his return from Africa, which mostly contains photos he took himself. “He made four copies and sent them to the influencers at the time, so to speak,” explains Andreas Eckl. Eckl acquired one of these copies privately, because he’s been working for over 20 years as an antiquarian book dealer with a particular passion for collecting objects of colonial history. The researchers will publish not only Trotha’s diaries, but also the photo album with more than 200 pictures.

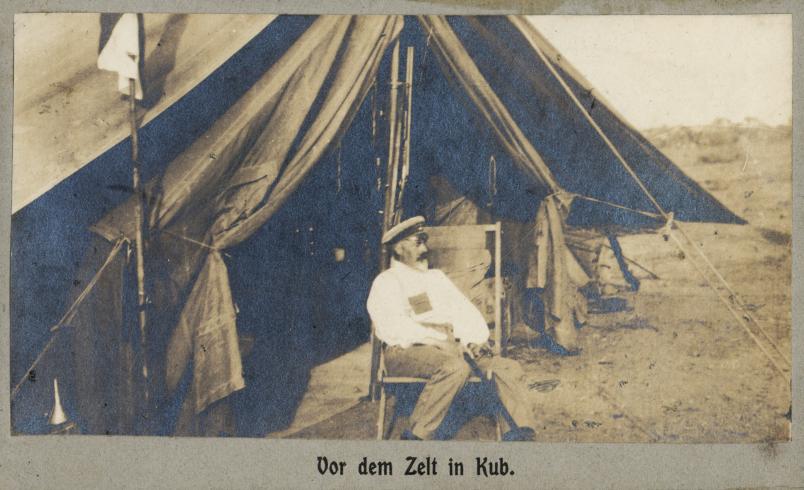

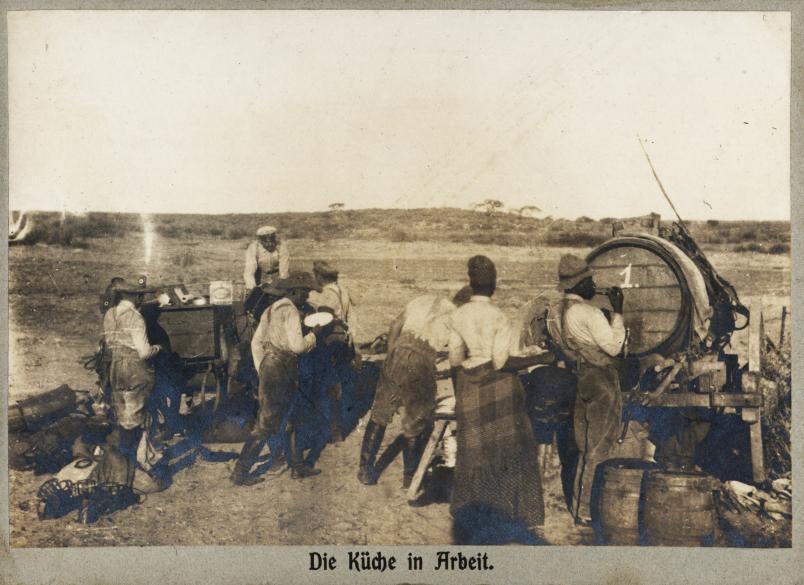

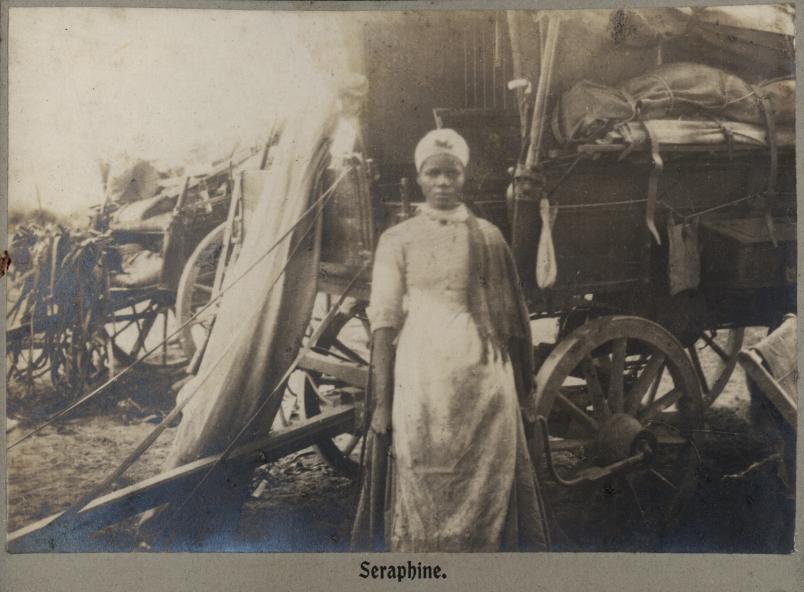

Unlike the diaries, which always record extraordinary incidents, the photos document everyday life in Africa. Only three of the 35 pages in the album are dedicated to the Herero campaign: there’s a photo showing the death of a German officer, for example, or shots from the field hospital. Other than that, the focus is on more or less touristic aspects: the photographs show landscapes, horses, a camp tent, officers eating or sleeping. There are also many pictures of Africans, although it usually remains unclear who these people were.

No indication of extreme racism

The researchers have not been able to identify any signs of extreme racism in either the diary or the photo album – even though Trotha is widely regarded as a race warrior par excellence. “This is quite surprising,” says Eckl. “Racist attitudes are expressed in other sources, for example by painting Africans as devious, cruel or lazy. Such ideas are not reflected in Lothar von Trotha’s notes or in his photos. This doesn’t mean, however, that he didn’t think in racist terms.”

A paperbound treasure

Eckl and Häussler point out that the commander-in-chief’s diaries and photo album were not exclusively personal mementos; rather, they were intended for the general public. Above all, this is true of the photo album. “In it, Lothar von Trotha tells his own story of the war,” says Andreas Eckl. This is because, after his return from Africa, he was not a celebrated hero. Criticism of his conduct of the war was certainly voiced. His writings and even more so his photographs were Trotha’s attempt to respond to this criticism. “They were meant to convey that there was nothing amiss with the way things had gone,” Eckl continues.

He was not just any war participant, and it is not just any diary.

Matthias Häussler

“For historians, these sources are a treasure whose importance cannot be overstated,” says Matthias Häussler, while Andreas Eckl adds: “Lothar von Trotha was the commander-in-chief of the German troops. He was not just any war participant, and it is not just any diary, but an outstanding source pertaining to the history of the German Empire. There’s nothing quite like it.” The photo album and diaries are scheduled for publication at the beginning of 2023.