Social science

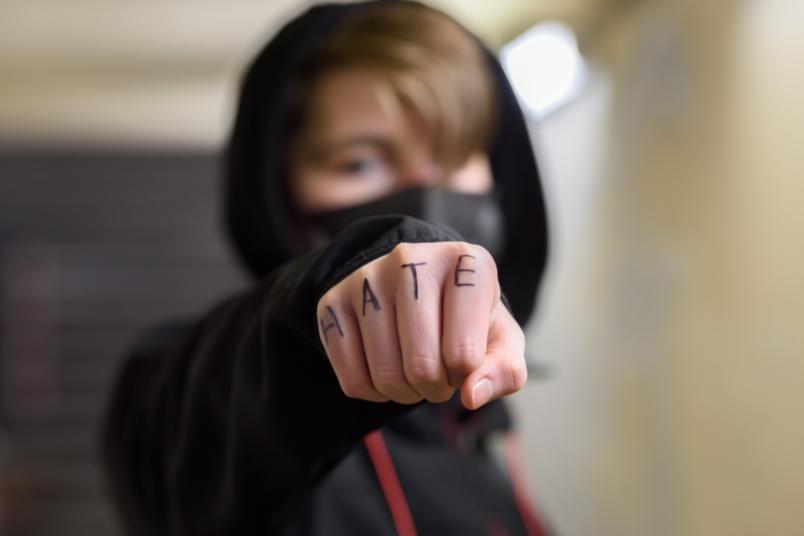

This is how hatred turns into words and deeds

What kind of people commit racially motivated acts of violence and what does this entail?

Shoving, punching, kicking, hitting, stabbing, arson: violent hate crime has many faces. A research team at RUB analyses its various manifestations, including how the offences take place and who commits them. “What makes our study unique is that we record what happens and the sequence of events, including the interactions between the individuals involved in them, in detail, in order to learn more about the dynamics of violence,” says Professor Cornelia Weins, Chair of Methods of Empirical Social Research. “What happens, exactly? How do the victims react, and what do people who witness the attacks do, for example passers-by or local residents?"

Focus on racially motivated violence

Weins and her project team, PhD students Juliana Witkowski and Sebastian Gerhartz, and Kai-David Klärner, are studying racially motivated violent crimes committed in North Rhine-Westphalia between 2012 and 2019: “By racially motivated crimes, we mean crimes fuelled by prejudice against ethnic or national groups, persons of colour and religious communities – in the case of the latter, it is mainly antisemitic and islamophobic acts,” explains Sebastian Gerhartz. Most of the attacks are directed against people who are perceived as belonging to these groups. However, people who stand up for them can also become targets of racially motivated violence, as was the case with the attacks on Henriette Reker and Andreas Hollstein in North Rhine-Westphalia. The RUB team is studying the crimes that are classified as violent offences in the official recording of politically motivated crime – ranging from minor assaults to arson and attempted homicides. “This means that we consider both, potentially life-threatening and serious attacks, as well as attacks with a lower intensity of violence, which can be characterised as everyday hate crime,” explains Gerhartz.

Data collection ongoing

The study is part of the research network “Connecting Research on Extremism in North Rhine-Westphalia” (CoRE NRW). It will be funded by the Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia until 2023. For their study, the researchers inspect documents from a criminal police reporting service on all acts recorded by the police as hate crime between 2012 and 2019 and in public prosecutor’s investigation files for cases where suspects have been identified. “Our findings from this project will enable us to make statements about all offences in North Rhine-Westphalia that are known to the criminal investigation authorities and have been recorded as violent hate crime,” said Weins. Data collection is still ongoing for 2017 to 2019. For 2012 to 2016, initial results have been compiled for a total of 800 cases of racially motivated violence from police documents and for more than 400 solved offences from investigation files.

Detailed insights into the incidents

Police documents and files contain in-depth descriptions of the crimes. These details are of particular interest to the researchers, as they provide them with information on what happened during the incidents. “We obtain standardised information about the incidents from the individual descriptions and then evaluate them statistically,” says Gerhartz. According to the RUB team’s assessment, most of the offences are initiated by the attackers, who are intent on and willingly embrace an escalation. Typically, the attackers and victims don’t know each other.

“More often than not, the attacks start with insults,” relates Juliana Witkowski. “The insults are usually directed against the presumed origin of the victims, their skin colour or religion. Violent attacks range from pushing and shoving, spitting, slapping, punching, kicking, choking, bludgeoning, throwing glass bottles or stones, stabbing, shooting, arson and bombing. During the period assessed in the study, the latter were primarily directed against refugee shelters. The majority of attacks didn’t involve any means of action; in most cases, the attackers hit or punch their victims. Most victims react by trying to protect themselves: they attempt to get help or draw attention to their situation, leave the scene of the assault and de-escalate the situation. In slightly more than 50 per cent of the offences, the victims defend themselves verbally, and in just under 50 per cent of the offences, they also defend themselves physically. In cases where third parties intervened, they get help, stand by the victim, try to de-escalate the situation, for example by appeasing the attackers, or intervene physically to protect the victims. The team is currently trying to identify patterns of interaction and contextual factors that go hand in hand with different dynamics of violence.

Violent hate crime no longer a youth phenomenon

Moreover, the team intends to find out more about the perpetrators: who commits hate crimes? One striking difference to earlier studies is age. According to a study for North Rhine-Westphalia, in the early 2000s slightly more than 70 per cent of perpetrators were younger than 25; in the period between 2012 and 2016, only 40 per cent belonged to this age group. “Racially motivated violence can no longer be described as a youth phenomenon,” concludes the research team.

Racially motivated violence is still male-dominated, female perpetrators are rare. Compared to the general population, they have a lower level of education and a significantly higher unemployment rate. Researchers identify dissocial behaviour and an affinity for violence as risk factors for radicalisation: “For a notable proportion of the suspects, the files provide evidence of previous convictions for violent offences,” says Witkowski. “And the majority of suspects are known to the police to have previously committed offences of some kind, politically motivated or otherwise.” However, the team’s initial findings on the backgrounds of the suspects in North Rhine-Westphalia don’t provide any evidence that more people from the mainstream of society are committing racially motivated acts of violence following the influx of refugees that took place in 2015/16 and fuelled right-wing populist mobilisation in society.

A large, right-wing perpetrator network

The research team also investigated whether the suspects were involved in any networks. They identified a number of smaller and one particularly large network of alleged organised right-wing offenders for the period from 2012 to 2016, who were linked through jointly committed offences. The group crimes committed by organised right-wing offenders from these networks still strongly shape our notions of racially motivated violence. However, the team’s findings also show that violent attacks and racist perpetrators of violence don’t necessarily fit this image.