Media Studies

Witness report from a fridge

Professional forensic investigators can tell a lot from digital data footprints. But they’re not the only ones.

Smart toothbrushes, light bulbs and fitness watches, connected garage doors and front doors with video recognition systems, personalised social media profiles and streaming accounts – we leave digital footprints wherever we go in our everyday life. The same goes for criminal offenders – to the delight of professional forensic experts, who now have a fleet of high-tech instruments and computer processes at their disposal for investigating these new media crime scenes. They can scan entire crime scenes in three dimensions and make them accessible in virtual space, and they can reconstruct the exact course of events by reading the sensors of smart refrigerators and lighting systems. In his book “Medien der Forensik”, Professor Simon Rothöhler outlines how such methods work. “Series franchises such as CSI or, most recently, true-crime formats, which often contain forensics elements, are very popular, especially on streaming platforms. Civil society investigative agencies like Bellingcat or Forensic Architecture also use forensics at the intersection of art and activism. We encounter forensics wherever we go in everyday life,” says Rothöhler.

[infobox: 1]

Institutional forensics

Let’s start with a look at institutional forensic practice: what do professional forensic investigators do, and what do they understand by ‘media’? “Forensic investigators are essentially all actors employed by the government and affiliated with the government who are called upon by criminal investigation departments and public prosecutors’ offices to participate in the investigation and analysis of criminal acts,” explains Rothöhler, who’s interested in an approach to forensics rooted in the history of media and science.

Media play a role at various points in forensic investigations: from the moment the professionals enter a crime scene and document the entire evidence using photographs or laser measurement, to the examination of samples in the labs when digital reference libraries are retrieved via computer networks, to the appearances of forensic experts in court where the findings must be compiled, presented and communicated in a way that lay people can also understand. “Forensics as an institutional practice is built around the investigation of trace evidence. This means that the trace is at the heart of it,” says the media scholar. In a way, the trace itself can already be understood as a mediator, because the trace is not the thing itself, but is a mediating agent, a remnant of action, something that is left over and has to be read out backwards. “On the one hand, the traces themselves can indeed be media and, as remnants, establish a connection to the past; and on the other hand, we also have technical forensic media that are particularly well suited to reading out traces,” explains Rothöhler.

Digital traces

Blood, hair, saliva residues, tyre marks – there is a multitude of physical traces and, consequently, just as many areas of expertise. “Media technology didn’t appear until quite recently in this list as an explicit field of expertise,” says Rothöhler. Digitalisation was the game changer. “Today, institutional forensics takes a close look at the digital dimension of crime scenes,” continues the media scholar. This is because the digitalisation of everyday life produces an enormous output of digital traces and data. Today, almost every action, every communication, every telephone call, every interaction leaves an information trail in its wake. “It is quite difficult to move through contemporary life and not be constantly tracked or leave other digital traces. Track and trace is everywhere,” points out Rothöhler.

New witnesses

The media scholar is referring primarily to devices that aren’t conventional surveillance systems, such as smartphones or even smart fridges, loudspeakers and heating units. All these everyday devices have network access and store data that can in turn be read out by forensic means. “The term media forensics covers not only media in the narrower sense, such as sound recordings and images, but everything that is built around the connected computer and is called the Internet of Things,” explains Rothöhler. And indeed, there have been cases where forensic investigators were able to apprehend and ultimately convict a murderer with the help of the sensors of a smart fridge. “Digital media are much less volatile than is generally assumed. The digital sphere is not a realm of the immaterial, either. Data is always physically stored somewhere. Data that has supposedly been deleted from hard disks and other forms of storage is often easy to reconstruct.” Computer forensics in particular takes advantage of this fact as an increasingly important subfield of professional media forensics.

A new approach to media forensic investigations

Inevitably, digitalisation has not only stepped up the volume of evidence; it has also changed the way forensic information is gathered by the investigating authorities, providing for new areas of application and more complex forms of evidence recovery. In order to determine whether digital image, audio or video material is genuine, media forensic experts today have to scrutinise the metadata and pixel structures for disturbances, manipulations and suspicious structures. Does anything indicate that the images have been tampered with, was faked? “Media forensic authentication usually just means that no traces of intervention can be detected,” says Rothöhler.

Virtual walk through of crime scenes

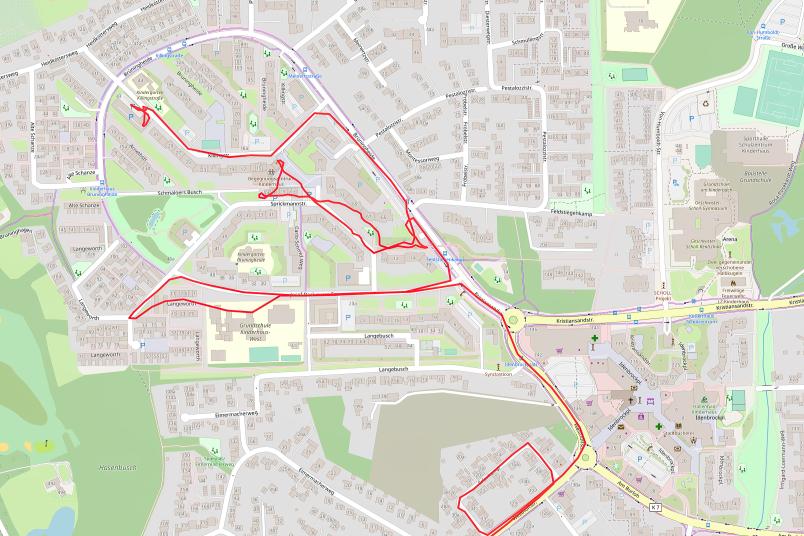

In order to trace and decode the complex data and digital transport routes, forensic investigators are relying to an increasing extent on computer-aided tools and highly specific software. “In professional forensics, immensely interesting applied media research takes place. Often, the most advanced techniques are deployed,” stresses Rothöhler. This is true, for example, in the field of crime scene photography. “Forensic investigators today use 3D laser scanners to measure rooms and thus freeze the crime scene visually. Eventually, the crime scene is virtually modelled and can be walked through,” elaborates Rothöhler. Some state offices of criminal investigation have entire holo-decks at their disposal to digitally recreate crime scenes, move the avatars of perpetrators, victims and witnesses and thus to verify statements. What could the witnesses actually see? How far away was the hand from the murder weapon? More than once, false statements have been thus exposed.

Physical limitations

Digital media also present a number of challenges for institutional forensics, for example when it comes to the question of where data that has been stored in the cloud is physically located or how to get at data that is located on servers outside Europe. “Digitalisation renders the entire search for clues more complicated, because the crime scene tends to be global as far as media are concerned. Digital data is distributed in a complex way – and is often the private property of large platform operators,” as Rothöhler describes the challenge of forensic evidence search.

Forensics in popular culture

In his book, Rothöhler speaks of a popularisation of forensics. “There is clearly a history of fascination with forensics,” explains the media scholar. If you take a look at literature, films, series or podcasts, you will always come across depictions of forensic practices that resemble each other. “Forensic experts are often the real stars, as on CSI. They stand in laboratories in their white coats, examine the smallest trace particles under the microscope and find the decisive, irrefutable evidence.” At the same time, media forensics has also become popularised in the sense that it has become part of our everyday life in a modified form, Rothöhler argues.

Paraforensic approach

“Every one of us, if we get an email from an unknown source, we will almost automatically google that person’s name, identify their social media account in the search results and then check what kind of content they enjoy, what they’ve liked, shared, commented on and so on. In other words, we are reading digital traces on a daily basis – just like forensic investigators.” This is also the case when we use social networks or look for restaurants or holiday destinations. All these common practices could be called paraforensics or pseudoforensics. We imitate real forensic investigators. “This is how we react to the complexity of digital media. We are aware that they are everywhere, watching us, registering us, suggesting shows and consumer goods to us in a calculating manner. One could also understand pseudo-forensic behaviour as a defensive reaction against the omnipresence of surveillance – or as an attempt at appropriation,” concludes Rothöhler. Naturally, pathological forms exist here as well – as in the case of media-sceptical conspiracy theorists, for example.

[infobox: 2]