Protein research

Where there’s a protein, there’s a perpetrator

When it comes to criminal investigations, it can make a difference whether a mucous stain at a crime scene is nasal mucus or semen. But it’s not easy to tell body fluids apart. This is where RUB comes into play.

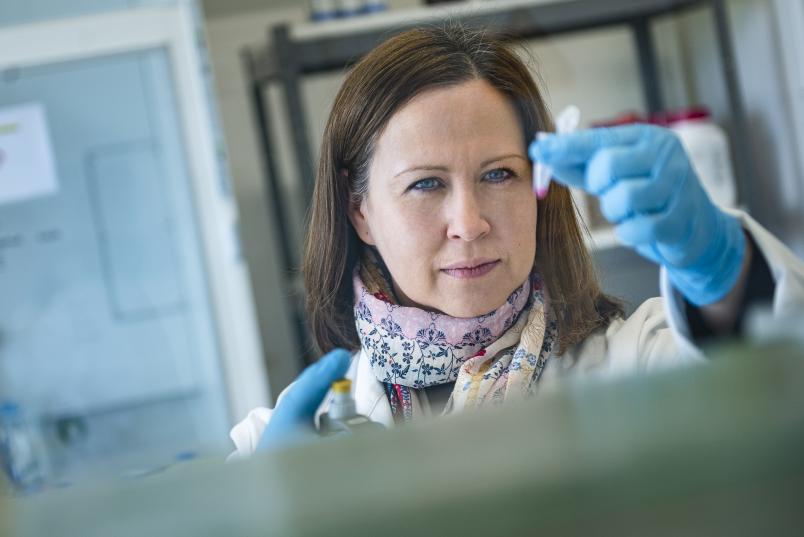

In order to solve a crime, every tiny trace can be crucial: a hair, a fingerprint, a few drops of body fluid. In order to get it right, investigators must be able to identify which bodily fluid is involved. Sperm or vaginal secretions, for example, can indicate a sex crime. “If a mucous substance is found in the bed sheet, the perpetrator could for example claim that it’s his nasal mucus because he is allergic,” as Dr. Katalin Barkovits-Boeddinghaus describes a possible application. She’s a researcher at the Medical Proteom Center at RUB. In cooperation with the state offices of criminal investigation in North Rhine-Westphalia and Bavaria, her team has developed a new method to tell different body fluids apart.

Established methods have drawbacks

There are, of course, established methods for identifying body fluids. “They work similarly to Covid-19 rapid tests. You put a few drops of the sample into a test cassette,” explains Barkovits-Boeddinghaus. This is how blood, saliva, semen and urine can be detected. For vaginal secretions, however, there is no effective method as yet. It can only be identified under the microscope by looking for certain cells. However, these cells are difficult to detect as they break down quickly.

In many cases, the available sample is very small.

Katalin Barkovits-Boeddinghaus

And the methods have another drawback: “You have to run a separate test for each body fluid,” says Katalin Barkovits-Boeddinghaus. “But in many cases, the available sample is very small. Then, investigators have to decide whether to look for saliva or semen, for example, because the sample may not be enough for both tests.”

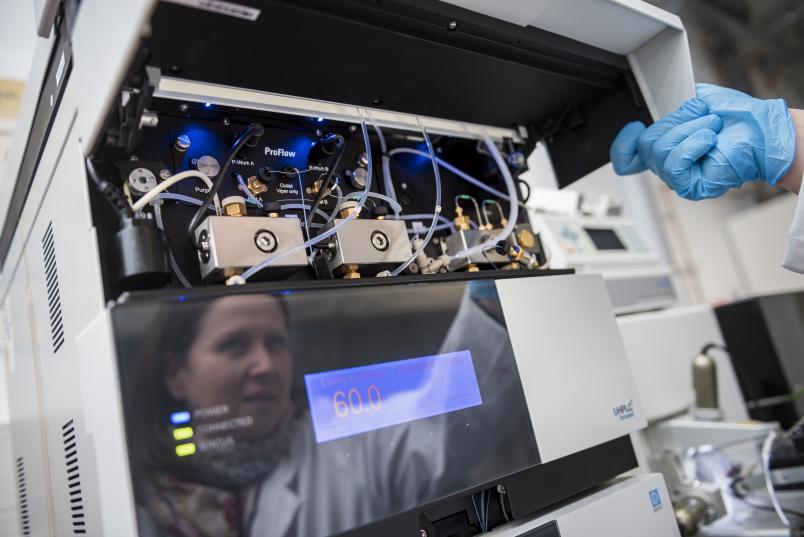

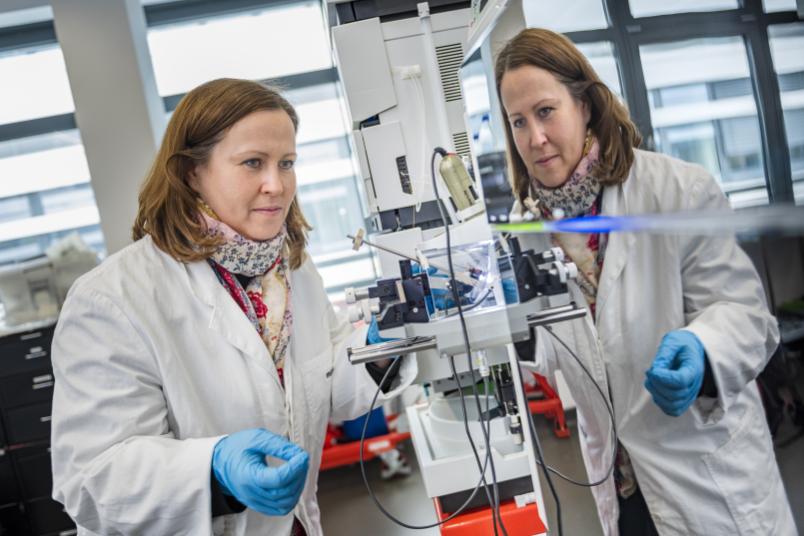

Funded by the EU’s Internal Security Fund, the RUB team and its cooperation partners developed a method that can analyse a tiny sample for the presence of blood, saliva, urine, semen and vaginal secretions at the same time. It is based on mass spectrometry, which can be used to identify all the proteins contained in a sample.

Mass spectrometry

Secretions have different protein compositions

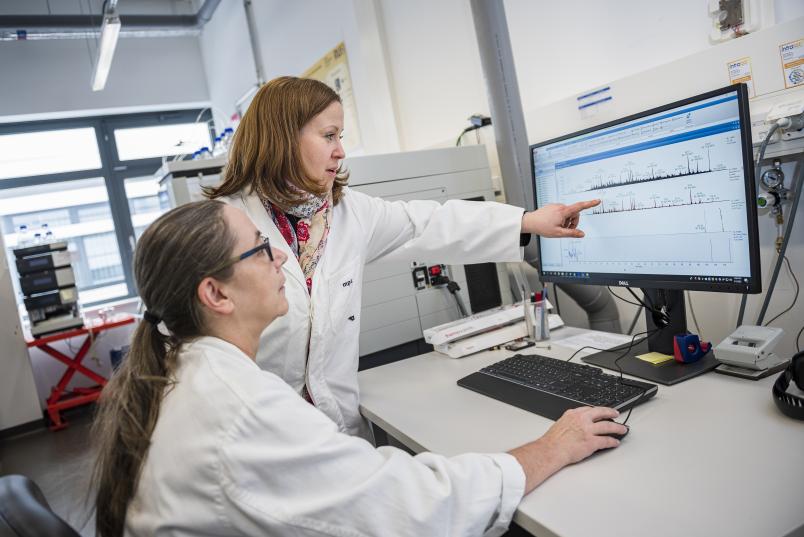

Since different body fluids have different compositions, the RUB team hoped to find proteins that only occur in one of the secretions respectively. The presence of protein 1 would then prove that it is saliva, while protein 2 would indicate vaginal secretion, and so on. In the first step, the researchers accordingly set out to find characteristic proteins, or more precisely peptides. This is because for the purpose of mass spectrometry, all proteins are broken down into smaller fragments, i.e. peptides. In order to identify so-called marker peptides, the researchers worked with samples of five body fluids from different test persons: blood, saliva, urine, vaginal secretions and semen, all of which often have to be identified in forensic analyses.

In the first step, they created an overview of all peptides that they could reliably detect across individuals in blood, saliva, urine, vaginal secretions or semen. Subsequently, they compared the data sets for the five body fluids and identified those peptides that only appeared in one of the secretions. They eventually identified five to six characteristic peptides for each body fluid.

Testing samples from state offices of criminal investigation

The state offices of criminal investigation that cooperated with RUB provided the research team with several samples without revealing what they contained. Using mass spectrometry, Katalin Barkovits-Boeddinghaus’s team looked for traces of blood, saliva, urine, semen and vaginal secretions in each of them – using a single test. The method reliably detected the five body fluids. The sensitivity was higher than with the established methods; for mass spectrometry, even smaller amounts of secretions were sufficient for the test to be successful.

The analysis also provides additional information: if blood, saliva, urine, semen or vaginal secretions are detected by mass spectrometry using marker peptides, it is also immediately obvious that the substance in question can’t be tear fluid, sweat or nasal mucus. “We can’t directly test samples for these three substances, but we can at least rule out the possibility that they are present.” This is because the applied marker peptides don’t occur in tears, sweat or nasal secretions. The above example of a sex offender who claimed to have allergies shows how important it is to eliminate such substances.

Entering a forensics competition

The method is so successful that the research group at the RUB’s Medical Proteome Centre now participates in the GEDNAP (German DNA Profiling) interlaboratory test every year. The competition serves as an external quality control. The participating institutions receive test items such as toilet paper, tampons, condoms or cigarette butts and have to analyse them. There are two categories: DNA analysis, which can be used to identify individual perpetrators, and the identification of body fluids; the RUB team participates in the latter.

“We took part in the competition for two years and have so far correctly identified 100 per cent of the samples,” says Katalin Barkovits-Boeddinghaus. However, the competition sometimes presented the researchers with challenges: “At one point, we had to analyse a piece of toilet paper, but we couldn’t even see where the body fluid was,” she recalls. “After all, we don’t have any regular forensic equipment at hand.” But a technical assistant on the team proved resourceful. She simply placed the toilet paper on the UV light table, which is normally used for analysing completely different samples in the lab, and the trace she was looking for became visible.

Collaboration with the state office of criminal investigation

Due to the restrictions imposed by the coronavirus pandemic on research projects, the team couldn’t take part in the GEDNAP competition in 2021. However, it plans to do so again in 2022. Contacts with the state criminal investigation offices in Bavaria and North Rhine-Westphalia have been maintained, even after the joint research project came to an end. Every now and then, the criminal investigators send the RUB team real case samples for analysis. To this end, they also worked out a workflow during the project. The samples are prepared at the state criminal investigation office, dropped onto a filter paper and sent to RUB by post in a dried state. “The proteins remain stable even in a dried state – we’ve checked,” says Barkovits-Boeddinghaus.

The researcher is currently looking into the possibility of offering mass spectrometric forensic analyses as a regular service at RUB. The method requires a high level of expertise, which she and her team could contribute to help solve crimes. “At the moment, however, we are not yet able to analyse the samples as quickly as would be required in real life scenarios,” she admits. In order to speed up the response time, the RUB team would need its own mass spectrometer that had to be reserved for forensic analyses and for which there was a full maintenance contract, so that the device would be repaired immediately if it ever breaks down. In addition, the analysis procedure itself would have to become even faster.

“At the moment, it takes us about one working day to get the final result. We would like to halve this time. We also want to automate the process as much as possible,” as Katalin Barkovits-Boeddinghaus outlines the outlook. At any rate, the RUB researchers intend to help solve crimes wherever they can in the future.