Psychology

Reclaiming your time off

Time off. Computer off. But the mind keeps going round and round in circles. And when the mobile phone lights up seductively, you’re quickly back at work. Marcel Kern is researching how to escape this spiral.

“My research has actually originated as a result of my personal experience,” says Marcel Kern, Professor of Work and Health at RUB. “I often found myself unable to switch off in the evenings and asked myself: why can’t I let go?” Many people are kept from falling asleep by thoughts that revolve around work even after the workday is over. Marcel Kern explores this phenomenon in his research. He investigates how digital technologies and remote work affect well-being and develops strategies that help people to reduce the stress caused by their jobs. To this end, he’s been closely cooperating with Professor Sandra Ohly from the University of Kassel for a long time.

“There’s a lot of research on digital technology and fatigue,” says Marcel Kern. It’s often assumed that people can’t switch off from work due to digital accessibility. But is this really due to digital media as such? Marcel Kern, Clara Heißler and Sandra Ohly set out to get to the bottom of this question. On five consecutive days, they had employees from different business enterprises fill out a questionnaire three times a day. How many hours did they use their mobile phones for work in their free time? Were there still many unfinished tasks left at the end of the day? How well could they switch off in the evening? These and many other questions were answered by 340 participants.

Digital technology alone will not cause stress

Every participant was required to have a work phone and a private phone. “This made it easier for us to separate the effects,” Kern explains. “In fact, a dedicated work phone should make it easier to switch off from work – but many participants weren’t able to do that despite having one.” Still, the stress wasn’t caused simply because they were using digital technology, but only when unfinished tasks were piling up that required them to use the technology. In order to recommend effective measures, the researchers must be able to distinguish between people who can’t switch off because they use their mobile phones and people who use their mobile phones because they can’t switch off. The latter seems more likely to apply.

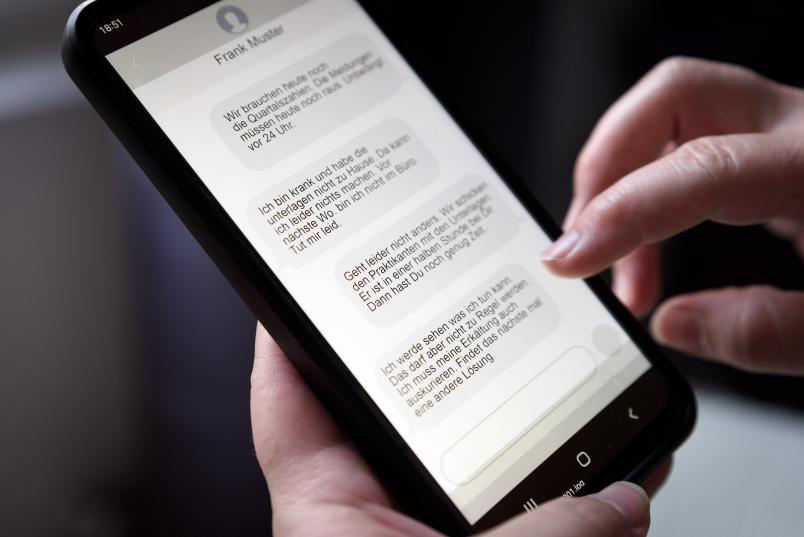

“After work, the business phone should be switched off, respectively push messages should be kept to a minimum,” advises Marcel Kern. It’s perfectly normal to sometimes drag work-related concerns into the evening, he says. “Often, these thoughts linger just below the surface – until you’re reminded of them when your mobile lights up,” he says. This is when you pick up your smartphone and your mind turns back to the job at hand.

Four tips to experience less stress and switch off more easily

The Bochum psychologist is looking for ways to stop people doing themselves a disservice by working too much. “The problem can’t be readily fixed by legislation,” he says. “There’s no global regulation that works for all employers.” He gives an example: “Volkswagen switched off its email servers in the evening. That led to people keeping emails in their outbox or even sending them from their private accounts.”

Not everyone looks to separate work and leisure

It’s important to remember that the use of technology in the evening can also be advantageous. For example, it’s easier for some people to put the children to bed first and then do some work in peace. “Some people also want their work and leisure time to merge,” points out Marcel Kern. In Germany, however, this only applies to one third of employees, at least to some extent. Two thirds prefer to categorically separate work and leisure time. Still, only one third manage to achieve this separation in reality. The rest have to be available to the employer outside working hours – or they feel that they do.

As Marcel Kern found out in follow-up surveys, it’s the attitude and behaviour of managers that usually makes people feel they have to be available at all times. The employees base their behaviour on that of their managers. And if those managers keep sending emails late at night, this makes the rest of the team think that they have to be available as well. In a study – once again in cooperation with Sandra Ohly’s team in Kassel – Marcel Kern explored methods to combat this problem.

Manager training improves satisfaction

Twenty-three managers of a commercial enterprise took part in a training course. During this training, the researchers made them aware of how their own attitude and behaviour can affect their employees. The researchers recommended, for example, to make explicit agreements with the team on after-hours availability. Or to explain why a manager might still send emails late at night – for example, because it’s easier for them to reconcile this with their childcare responsibilities.

The managers hadn’t been aware of the impact of their own behaviour.

Marcel Kern

The researchers interviewed the managers’ employees before the training took place and about six weeks afterwards: when did they think they had to be available for their organisation? Were they able to switch off in the evenings? How stressed were they by their job? “The results were conclusive,” as Marcel Kern sums up. “The employees felt much better after the intervention. This came as a surprise to the managers. They hadn’t been aware of the impact of their own behaviour.”

Information flood in the inbox

This means that minor changes can have a huge impact on employee satisfaction. In addition to agreements on availability, Marcel Kern knows of other potential levers: “Many people experience an email overload, and the sense of information overload affects their well-being,” he says. He’s also conducted research on this issue together with Sandra Ohly.

Studies on email overload already existed, but they’d lumped all types of emails together. Ohly and Kern, on the other hand, distinguished between emails stating concrete tasks, e.g.: “Please finish the presentation by next week”, and communicative emails, for example those explaining a new process. “Communicative emails are often the typical Cc emails,” explains Kern. And it’s precisely these that contribute to a feeling of information overload.

People have a hard time dealing with interruptions.

Marcel Kern

He recommends the following remedy: “It makes sense to agree in the team who should receive which information. Some employees always put the manager in Cc, because they believe this is necessary to make their work visible. This is where prior agreements can be helpful.” Another solution could be to bundle emails. One email with accumulated information sent once per week or per month is more easy to digest. What’s more: “People have a hard time dealing with interruptions,” says Marcel Kern. “The ping of an incoming email is enough to break our concentration; we are curious creatures, after all.”

Less push, more ease

He has since incorporated the results of his studies into his own behaviour – and is noticing positive effects. “I’ve switched off push messages as much as possible,” he reveals. “Sometimes, it takes me 24 hours to respond to a WhatsApp message.” At first, others were irritated. Today, everyone’s got used to it. The result: “I can definitely switch off better now.”