Psychology

My colleague, the avatar and me

A psychology team at RUB is interested in how work processes can be optimised in teams that work in different locations. The researchers put their faith in augmented reality.

All of a sudden, nothing was the same anymore. Coronavirus has shaken up the work processes in many companies and public authorities. Suddenly, working from home had to be the norm, where before it had been the exception. The question of how teams function when they aren’t in one location became the focus of the working world from one day to the next. At RUB, that’s already been the case for some time.

Several research projects in Professor Annette Kluge’s work group are exploring how teams that are spread across different locations can best work together. This is because people who can’t speak directly to each other and can’t see each other inevitably encounter many hurdles. “The handover moments where one person has to pick up where another left off often lead to time being lost,” says Lisa Thomaschewski. Together with colleagues at the Chair of Work, Organizational, and Business Psychology, she’s looking for solutions that could render daily routines easier in the future – namely in the field of augmented reality.

Augmented reality as assistant

“Originally, we looked into organisations such as fire brigades, the military and even refineries,” says Thomaschewski. In such organisations, employees often work in different locations, and mistakes can have devastating consequences. “A time lag can be all it takes to compromise safety,” says the psychologist.

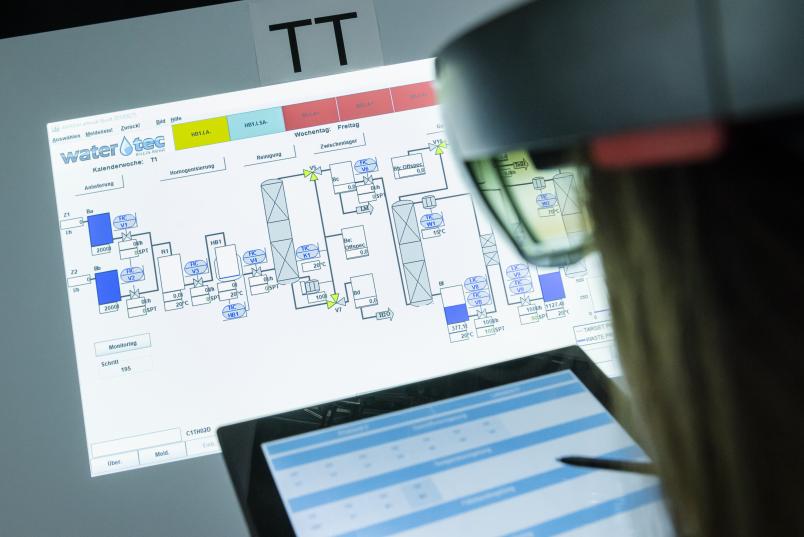

Processes in high-reliability organisations are difficult to research, however, simply because it could be too dangerous for everyone involved. Therefore, the researchers are looking at application examples from the manufacturing industry, which faces similar challenges. Here, the goal of process optimisation is to achieve the highest possible productivity. “We wanted to know what tools could be useful for this purpose and quickly came up with augmented reality,” explains Lisa Thomaschewski. She works with HoloLens, augmented reality goggles that can superimpose virtual information on real-world objects. The advantage of this technology is that it leaves the hands free. This is convenient when, for example, users have to operate a complex control panel. Another advantage is that the technology can be introduced into a company without having to interfere with existing systems.

Teamwork essential for simulated wastewater treatment

For their study, the researchers use an established simulation of a wastewater treatment plant. Thirteen steps have to be completed in the right order to control it. For example, valves have to be opened or closed and tanks filled. If the aim is to obtain as much purified water as possible, a good timing is also crucial. The RUB group adapted the simulation so that it has to be operated by two people in a team. Each person has to perform several of the 13 steps in turn, and always at the right time once their partner has completed their task.

To make the whole thing a little more difficult, the two participants also must solve an individual task. Each person operates a second wastewater treatment plant alone, which also has to produce as much purified water as possible. “In a real-life scenario, employees working in a team usually can’t focus on just one task, but have to complete other tasks at the same time,” explains Lisa Thomaschewski.

For the experiments, the two participants were located in two separate rooms without being able to communicate with each other. Each person used a tablet to control their own wastewater treatment plant as well as their respective team tasks. The simulations for the individual and team task were shown on two different screens at a 90-degree angle to each other. To switch from the individual task to the team task, the participants thus had to turn around and could not observe the parallel job out of the corner of their eye. 110 two-person teams participated in the experiment, which took about four hours for each pair to complete.

Two tools to assist with the task

For the experiment, the participants were provided with the so-called Ambient Awareness Tool. The RUB team developed it together with the group headed by Professor Benjamin Weyers from the Human-Computer Interaction group at the University of Trier. Via the HoloLens, it displayed information on the status of the plant to the test participants, which would otherwise not have been visible. The participants saw three icons in the HoloLens, each of which indicated the next steps to be taken in the two tasks. If the next step was ready to be carried out – for example, because the partner in the team task had finished their process step – the icon started to flash. The participants didn't have to constantly check how far the second person had got with their task. The tool signalled when it was their turn. This allowed them to concentrate on their other task in the meantime.

A Gaze Guiding Tool was used as an additional aid: in the HoloLens, the object of the wastewater treatment plant that had to be dealt with next was always highlighted in colour. In addition, a text was displayed indicating what had to be done with this object. The researchers compared how efficient the participants were at the task when they only had the Gaze Guiding Tool at their disposal versus when they could also use the Ambient Awareness Tool. “The results are not conclusive, however,” concludes Thomaschewski. “We already know from previous studies that the Gaze Guiding Tool supports error-free operation. We’ve also noticed a tendency that the participants work more efficiently when using the Ambient Awareness Tool, but we can’t yet make any reliable statements about this at this point in the evaluation.”

A progress bar for team spirit

In addition to the tools described above, the researchers tested whether an additional progress bar improved the timing coordination of the teams. It was positioned above the object indicating the next task and signalled when the next step could be tackled. This didn’t improve the timing of the task. However, the progress bar improved team cohesion, a measure of the sense of belonging to a team, as the researchers found out with questionnaires. “We believe that the bar is perceived as a social cue: it creates the impression that there’s another person out there,” assumes Lisa Thomaschewski.

Because team spirit is important to the researchers, they are currently experimenting with another technique, which is still in its infancy. Instead of the abstract objects of the Ambient Awareness Tool, they are using HoloLens to display the avatar of the respective team partner. The participants thus see a projection of a person through the goggles who can, for example, point in the direction of the next process step. The researchers were not yet able to test the complex wastewater treatment plant as a team task using this method. First, they tested its feasibility and wanted to know how people react to the avatars.

For this purpose, participants – this time without their respective team partner – had to read individual levels on the simulation surface. They saw the avatar pointing in the direction of the part of the system that had to be read. In a second experimental condition, the avatar simply stood still in the room without interacting. Accompanying surveys with the participants showed that, as expected, the moving avatar was perceived as more realistic and reinforced the feeling of not being alone.

The vision: team members as avatars

This is where the psychology team now intends to conduct more in-depth research. Which role does the gender of the avatar play? What happens when it approaches the participants or moves away? Do they move with it? And can the avatar be used to increase efficiency in the simulation of the wastewater treatment plant?

Our goal is to create a workplace that is visually shared across physical distance.

Lisa Thomaschewski

Once the technology is perfected, the team partner could be projected as an avatar at their colleague’s location, so that the colleague could see what their partner is doing – this is what the researchers have in mind. “Our goal is to create a workplace that is visually shared across physical distance,” points out Lisa Thomaschewski. Yet she knows that this research will not find its way into the professional world any time soon. “Augmented reality goggles have not yet caught on, because the technology is simply not advanced enough,” she explains. In two to five years, things may look quite different. Then, the goggles could facilitate the work of teams that work in different locations.