Psychology

Less crazy together

Why do we tend to like people who share our interests – and why do we like people even more if they share our most unusual tastes?

Musician Tom Waits kicked the whole thing off. “It’s not very often that you meet someone who likes him as well,” says Waits fan Professor Hans Alves. “Whenever I happened to meet someone who likes him, too, I immediately found myself being drawn to that person.” As professor of social cognition, this phenomenon naturally piqued his scientific interest. After all, various studies had already shown that sharing the same interests makes us feel an affinity towards each other. But does sharing an unusual interest increase this affinity even more?

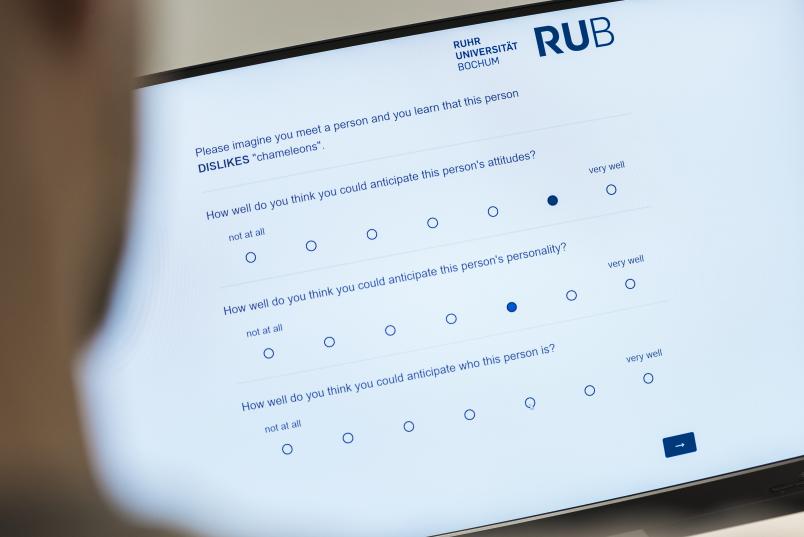

Together with his colleagues, Alves explored the phenomenon of mutual affinity in a number of surveys. The researchers surveyed the attitudes as well as the likes and dislikes of their test participants in several online questionnaires. Which books do they like to read? What do they like to eat and drink, what don’t they like? Which films do they watch and which do they avoid? What about celebrities? Hobbies? Holiday plans? The participants’ answers ranged from standard statements such as “I like holidays in the sun”, to quirky hobbies such as dressing up in fancy costumes.

When strangers first meet, they look for a common frame of reference.

Hans Alves

In the next step, the researchers invited the participants to imagine meeting someone who had provided the same answer to one of the questions as they had. How keen would they be to get to know this person better and spend time with them? “It turned out that sharing the same interests makes people more likely to like each,” points out the psychologist. “And what’s more, unusual interests have a greater impact than interests that are shared by many people.”

The researcher offers several possible explanations for this fact. For one thing, people bond with each other through shared similarities. “This is true even for coincidental similarities such as sharing the same birthday or the same name,” says Alves. When strangers meet, they look for a common frame of reference – and this is where they find it.

“Furthermore, when we meet someone who shares our attitude, it gratifies our desire for approval,” as Hans Alves outlines yet another reason. By sharing our world view, the other person validates us. This helps us to uphold a positive self-esteem. “Our need for validation is particularly great when it comes to unusual attitudes or inclinations,” says Alves. “If we find there’s another person around who shares them, it tells us that we’re not alone, that we’re not actually crazy.”

Uncommon attitudes tell us more than common ones

And there’s yet another attempt at explanation: uncommon attitudes tell us more than common ones, they reveal more about how much we resemble another person. “We experience this as a kind of alliance – it’s us against the world,” describes Hans Alves. Moreover, the thing that sets a person apart from the average is the very thing that is at the heart of their personality. It is primarily through their quirky traits that we get to know other people better in all their idiosyncrasies.

“We also looked into this aspect in the context of dating,” says Hans Alves. “We asked our survey participants: how eager do you think you’d be to meet this person?” Again, respondents expressed a greater inclination to meet someone when their unusual interests matched. “If I were running a dating platform, I’d make sure to match exactly such details,” points out Hans Alves, who, however, has no insights into the algorithms of such platforms. “This information is not communicated to the public.”

Common ground through shared dislikes?

Still, there are other reasons why it’d make sense to look for such matches, as literature suggests that they’re more important for the success and duration of a relationship than personality traits. “Matching attitudes towards the relationship play a significant role – should it be open or exclusive, do both partners want children, and if so, how many?” illustrates Hans Alves. “Just as important are people’s attitudes towards drugs, alcohol, politics and many other issues, because the potential for conflict increases if they don’t match.”

Hans Alves and his colleagues examined the importance of preferences for mutual affinity at even greater depth and evaluated the effects of shared dislikes in this regard. “Some previous studies indicated that people who share negative attitudes are drawn to each other more strongly than people who share positive attitudes,” says Alves. “But these studies had some methodological weaknesses, which is why we conducted another online survey to investigate this matter in more detail.”

It emerged that shared positive attitudes increase mutual affinity to a greater extent than shared dislikes. The researchers were not surprised. After all, most groups define themselves by something they like, be it football, music, or crafts, to name but a few. “Generally speaking, people who are positive about something are liked more than those who disapprove of things,” concludes Hans Alves.

And there’s yet another argument to suggest that shared interests create a stronger affinity: liking something says more about a person than disliking something. “When people have a strong preference for something, they often have similar reasons why they like it specifically,” elaborates Hans Alves. This too has been scientifically proven in surveys. “By contrast, there can be countless different reasons for disliking something. It’s a bit like the opening sentence of Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’, which goes: ‘All happy families are alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ There’s definitely a grain of truth to that.”

Why might you dislike Robert Habeck?

Generally speaking, negativity has more diverse facets than positivity. “If I tell you I’m healthy, you already know a lot about me. But if I tell you I’m ill, you still have no idea which one of all the conceivable ailments I might have: a cold, cancer, arthritis? The possibilities are endless,” points out the researcher. The same goes for likes and dislikes. Two people who like the same thing often have similar reasons for their preference and can deduce a lot about the other person by knowing that they share their taste. If two people dislike the same thing, they might dislike it for different reasons. Let’s say two people both like Robert Habeck – this means they probably both vote for the Green Party and share the same values and views. If two people dislike Robert Habeck, it might be because one of them is an environmental activist and the other one votes for the right-wing AfD party.

In order to explore the effects of matching attitudes in greater detail, Hans Alves and his students have launched a new study. It focuses on the following question: if two people consider their own character traits in the same negative light – what effect does this have on their mutual affinity? Will two people like each other more because they both feel that they tend to be too anxious, for example? “The emerging evidence is that this is true, as long as the trait they dislike doesn’t hurt others,” as the researcher sums up his preliminary findings. “If two cholerics come across each other, both of them struggling with their choleric nature, who could at the same time hurt each other due to their short fuse, they wouldn’t end up liking each other just because of their shared character flaw.” Unless, that is, they discover that they share a common interest – their appreciation of Tom Waits, perhaps.