Religous Studies

From an oasis in the middle of the desert to Bochum

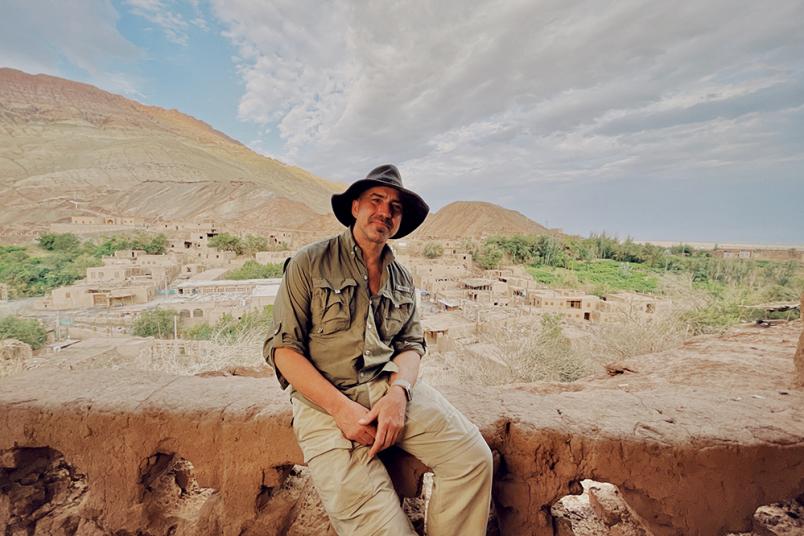

Neil Schmid has already lived in big cities such as New York, Paris and Tokyo, and most recently in the solitude of the desert. He is conducting research at CERES for three months.

Neil Schmid is a guest researcher at the Center for Religious Studies (CERES) at Ruhr University Bochum. In this interview, he talks about his last years in the desert mountains of Dunhuang, almost 2.500 km west of Beijing, northwest China, and what he experienced on his journey from parts west to China.

Welcome, Neil. We are very happy to have you here at CERES in Bochum. Can you tell us something about where you grew up and how your career started?

First, let me thank Professor Carmen Meinert and CERES for the kind invitation to come to Bochum for three months of research. I’ve been a cooperation partner with the ERC-funded BuddhistRoad Project since 2021, so my stay is a much-appreciated opportunity to finally spend time with scholars here that over the past four years I’ve only seen via Zoom calls.

As for the origins of my career, I grew up in Europe and the US, and was always fascinated by ancient civilizations and archaeology as a child. That ongoing fascination led me to study classical Chinese and Sanskrit at university, but it was spending time in China and travel to Dunhuang, a small oasis in the Taklamakan Desert, that led to a career in Buddhist and Dunhuang Studies, the study of the archaeological finds in and around Dunhuang.

I’m the first (and still only) full-time foreign researcher the Dunhuang Academy has ever hired so the invitation was quite an honor.

Near Dunhuang is a collection of 735 caves carved in a cliff face from the 4th to the 14th century, the Mogao Grottos, that contain the largest collection of Buddhist mural paintings and sculpture in the world. And it was here that in 1900, a monk discovered the largest medieval collection of over 60,000 manuscripts in multiple languages and scripts, together with paintings and votive objects hidden in a small cave nine hundred years earlier. That first visit some thirty-seven years ago to Dunhuang and the Mogao caves, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, set off a chain of events that led me to study in Paris, Tokyo, and Philadelphia where at UPenn I finished my PhD on Chinese Buddhist liturgical texts discovered at Mogao.

When did you decide to focus on Buddhism in China and to move there? And now you work at this site – how did that come to happen?

It’s quite remarkable because I never expected to actually live and work in Dunhuang. After teaching as guest professor in the Art Department at the University of Vienna, I went to the Dunhuang Academy as visiting scholar, and Director Wang Xudong, now the head of the Palace Museum in the Forbidden City in Beijing, kindly invited me to come to the Dunhuang Academy for a permanent position. I’m the first (and still only) full-time foreign researcher the Dunhuang Academy has ever hired so the invitation was quite an honor. For me a post at the Academy, in situ so to speak, is the ideal position to explore and develop my passion for all things Dunhuang in ways otherwise not possible. The unique opportunity to spend thousands of hours in the Mogao caves and other nearby sites over the past six years has been invaluable in developing new directions in my research, which I deeply appreciate.

Did you sometimes miss the hustle and bustle and the many people around you? What it so special about the mountains of Dunhuang?

Not at all! After having lived in major cities such as New York, Paris, and Tokyo a chunk of my life, I relish the isolation of living in an oasis in the middle of the Taklamakan Desert. And it is isolated; I’m the only resident westerner for four or five hundred kilometers, which always makes for interesting experiences. The landscape is spectacular around Dunhuang, with desert wastes, unimaginably high sand dunes, and 6,000 meter mountains with glaciers. And, of course, the region, being an important part of the Silk Road, continues to divulge new archeological secrets and discoveries. Furthermore, that key position has been reassumed today given the site’s importance in terms of heritage and geopolitical developments. It’s quite exciting being in the thick of it.

People ask a question I must ask myself sometimes, why live in such a remote and isolated location, and I have to say that it really comes down to awe.

How long did you spend time there and what was your research objective?

I have now been at the Academy for over six years, and I’ve had several projects, including creating a guide to Dunhuang Studies for western scholars, parts of which I’ve presented in a BuddhistRoad Guest Lecture Series. As someone who’s been on the ground in China working at a Chinese research institution, I have experience and insights into current trends and ongoing developments in Silk Road and Dunhuang Studies in China I’d like to share with western scholars, especially over the past few years when travel has been difficult.

What fascinates you most about your work?

People ask a question I must ask myself sometimes, why live in such a remote and isolated location, and I have to say that it really comes down to awe. I have an ongoing and profound sense of wonder for the archaeological site where I work; it’s a jewel set in an otherworldly desert with its endless array of human creativity and artistry, which in turn is seamless blend of cultures and thousands of years of history. The diversity and detail of the spaces, murals, and tens of thousands of manuscripts and texts discovered there give us such profound insights in all aspects of the daily lives of people more than a thousand years ago. For me it’s a kind of laboratory where I can test hypotheses and ask new questions not possible anywhere else. It’s a site that is at once profoundly human and extraordinarily transcendent.

How did you get in contact with the Ruhr University Bochum and CERES?

Henrik Sørensen, the former Research Coordinator for the BuddhistRoad Project, reached out to me to give a talk online for BuddhistRoad in 2021. The talk went very well, and I was delighted to find a like-minded group of scholars on the other side of the planet. Our interactions grew from there, and Carmen Meinert invited me into the project as cooperation partner later that year with a lecture series on Dunhuang Studies to follow.

It's precisely this new project that makes CERES such an ideal venue.

Why did you choose to come to Bochum?

During the past few years in my ongoing conversations with colleagues here in Bochum, it was clear to me that scholars at CERES have created a truly unique and highly productive collection of projects and individual under one roof. That range of fields, disciplines, and methodological approaches is hugely appealing, not only for their diversity but also for the simple fact that so much interdisciplinary dialogue happens among projects. Over the past few years while on my desert island I’ve gathered immense amounts of data, and a few ideas, that I’d like to explore and build on. Having the expertise of my colleagues at CERES and hearing their feedback and thoughts will be enormously helpful.

What exactly are you working on now?

Well, yes, it’s precisely this new project that makes CERES such an ideal venue. In the past couple of years, I’ve discovered a remarkable constellation of elements on a 10th century donor portrait of the King of Khotan, an oasis about 1,500 km to the west of Dunhuang, at Mogao that have previously been overlooked and which point to distinct influences from Sasanian Persian ideas of sacral kingship. What’s remarkable is that these rather distinctive ideas – as a coherent set – have persisted and continue to hold sway four hundred years after the fall of the Sasanian Empire and in a place as far afield as Dunhuang. These new discoveries are quite exciting not only for the invaluable information and insights into non-Buddhist Khotan, of which we know very little, but also into the transfer of ideas and material culture across Central Asia over time. Was there a coherent, shared model of kingship in diverse Central Asia cultures during late Antiquity and beyond? If so, what are the textual, material, and conceptual traces of this model? How do those traces help us recalibrate what we know about the political and religious cultures where the model was prevalent? These are large questions, and having the range of scholars and expertise in religions from Central to Western Asia found here at CERES to begin exploring them which couldn’t be more ideal.

Where will your research journey take you next?

We’ll see!