Interview

A Game of Life and Death

A ball game was at the center of life in the Mayan civilization of the Stone Age. It decided wars, agriculture – and presumably even the continued existence of the world. Not infrequently, it ended in bloodshed.

Higher, faster, further – that’s what modern competitive sport is all about. But performance was not necessarily always defined in this way, according to sports historian Professor Andreas Luh from Ruhr University Bochum. He researches the exercise practices of pre-modern cultures such as the Maya and ancient Egyptians and believes that the identity of a culture can be captured by defining the concept of performance. In our interview, he explains what this means for the Maya.

Professor Luh, since when have humans been practising competitive sport?

The modern idea of sport, which is about running faster and scoring more goals than others, became popular with the advent of industrialization. It came from England and replaced German gymnastics, which was rather more community-oriented. Its origins date back to the 18th, and in some cases even the 17th century.

It’s a deeply human trait to want to outperform others – as evidenced by overtaking maneuvers on the highway.

Still, even as far back as ancient Greece, people wanted to beat their competitors and to be faster than them. It’s a deeply human trait to want to outperform others – as evidenced by overtaking maneuvers on the highway. In the past, however, the concept of performance had a different definition than it does today.

Where, for example?

In Ancient Egypt, for example, or among the Maya, where physical performance was not used to stand out as an individual, but was crucial for the common good.

Which sport did the Maya practise?

I wouldn’t describe it as sport, but as an exercise culture that was integrated into the religious world view of the Maya. There was a ball game in which the ball represented the life-giving sun and had to be kept in motion to avert harm from the earth.

The Maya lived under harsh geographical and climatic conditions, suffering from floods, droughts, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. They believed that their world was destroyed and recreated at cyclical intervals. Their environment was ruled by hundreds of gods. A veritable mania for sacrifice prevailed in order to ensure that the world would be reborn. Their exercise culture was also geared towards this idea.

Imagine Manuel Neuer’s heart being cut out after FC Bayern Munich beat Mainz 8:1! That sounds disturbing to us, doesn’t it?

Was the ball game associated with sacrifices?

Yes. Two teams competed against each other in the game. In times of need, the winning or the losing team was sacrificed at the end of the game. There are numerous frescoes and reliefs that show the team captain having his heart cut out or his head severed, with plants sprouting from his blood and new life growing. Imagine Manuel Neuer’s heart being cut out after FC Bayern Munich beat Mainz 8:1! That sounds disturbing to us, doesn’t it?

Especially disturbing is that it’s the winners who may be sacrificed.

It’s not clear from the sources whether winners or losers were sacrificed. There’s evidence for both. One argument why it may have been the winning team was that they were imbued with greater strength.

Were there any referees? After all, the stakes were extremely high.

We don’t know exactly, nor do we know how the points were scored. What we do know is that it wasn’t a spectator game among the Maya, but a religious ritual. But the game must have been regulated somehow.

What were the rules?

The aim was to prevent a solid rubber ball, with a weight of two to four kilograms, from hitting the ground and to keep it moving. Throwing and shooting were forbidden. The players could make contact with the ball only with two parts of their body, for example their right shoulder and left hip. The game was played on a field with color-coded zones and lines. Over 1,500 Mesoamerican ballcourt have been excavated, and the ballcourt that can still be seen today in Chichen Itza measured around 135 by 90 meters. There were two rings on the wall; if the ball went through them, the game was over immediately. It was acrobatic and extremely physically demanding, and the players wore protective leather equipment.

How many players in a team?

A team consisted of two to seven players. They were prisoners of war, but often also members of the priesthood, who were prepared to sacrifice themselves for the common good in times of need. The game was a divine ritual to ensure the continued existence of the earth. Sometimes the game was also played to determine the time for sowing or when a war should begin.

The Maya are often portrayed as a peace-loving culture. Do these findings support this image?

Recent research has relativized the opinion of the peace-loving nature of the Maya. The Maya were prepared to sacrifice everything they had, including their children. They sacrificed hundreds of people every year. In other Central American cultures, such as the Aztecs, it was even tens of thousands per year. Ultimately, for the Maya, damaging the body to the point of self-sacrifice in order to sustain the community was the ultimate sporting achievement, so to speak.

We obviously can’t take the Maya as our role model. But we should consider what performance means to us and what is perhaps also problematic about our current concept of performance.

I find many things about Mayan culture fascinating, such as the fact that they didn’t strive for individual glory. We obviously can’t take the Maya as our role model. But we should consider what performance means to us and what is perhaps also problematic about our current concept of performance.

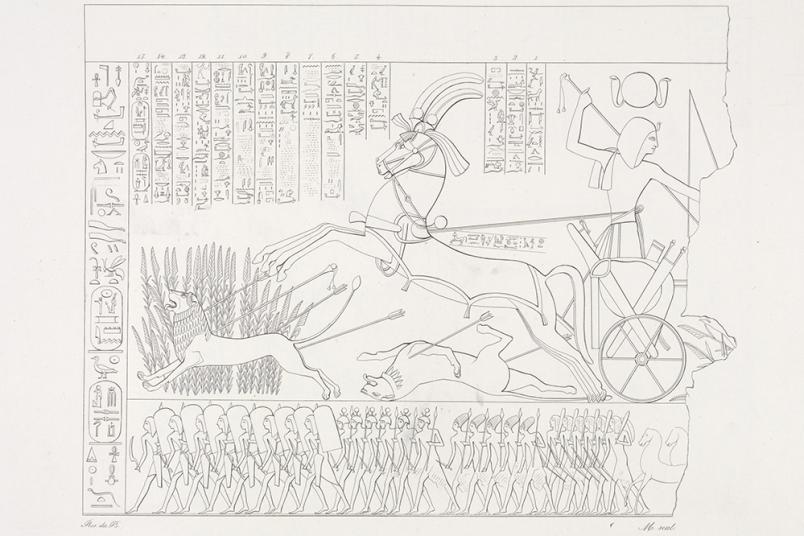

The ancient Egyptians