Neuropsychology

Why a Spider is Scarier in the Cellar Than in the Therapy Room

Letting go of learned fears is difficult. New research findings reveal that the environment in which we learn the fear could also play a crucial role in unlearning it.

At home, Nikolai Axmacher learned that it is bad manners to slurp when eating soup. The professor of neuropsychology at Ruhr-Universität Bochum now often travels to China, where not slurping soup is considered impolite. This is just one example of the importance of context, which Axmacher is researching in the Extinction Learning Collaborative Research Center.

“Normally, what we learn tends to be generalized,“ he explains. “This means that we can also apply what we have learned in other contexts. For instance, if someone passes their driving test in France, they can also drive a car in Germany.“ Only when the context is no longer valid, such as when eating soup in China, do we become aware of it and its importance. We normally cope with this by adapting our behavior.

However, the context plays a bigger role when it comes to getting rid of something we have learned, such as a phobic fear. “Someone with a fear of spiders is afraid of them no matter where they encounter them,“ explains Nikolai Axmacher. If this fear is very restrictive for the person, they may perhaps visit a psychotherapist and undergo exposure therapy. Accompanied by the expert, the patient gradually learns that the spiders in this country are harmless and there is no need to be afraid of them. Eventually, the patient remains completely calm when encountering a spider – at least in the psychotherapist’s practice. “However, when they go home and encounter a spider in the cellar, the fear is often present again,“ says Nikolai Axmacher. “It clearly depends on the context in which the unlearning took place.“

Electrodes in the brain record neural activity

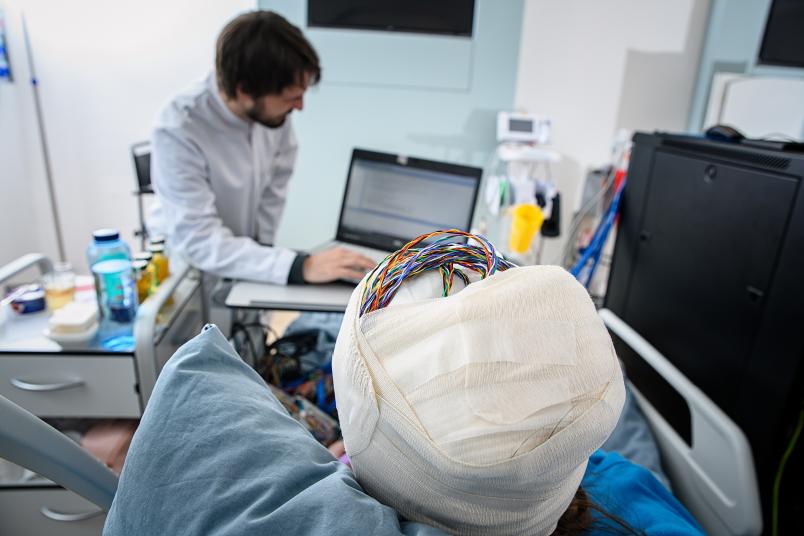

Axmacher aims to investigate this context dependence more closely in the Collaborative Research Centre. What happens in the brain when we learn or unlearn something? Researchers are investigating these questions using functional magnetic resonance imaging on healthy subjects. However, Axmacher gains a higher time resolution and more direct insights with intracranial EEG recordings, where electrical signals from the neurons in the brain are measured directly by electrodes, while the participant – in this case an epilepsy patient – takes part in an experiment.

To apply this method, Axmacher’s team is cooperating with Ruhr Epileptology at Knappschaftskrankenhaus Bochum led by Professor Jörg Wellmer. The neurologist treats patients whose epilepsy cannot be controlled with medication. To plan the surgical procedure precisely, the specialists must first find out exactly where the point of origin of the patient’s epileptic seizures is located. To do this, they insert electrodes into the suspected areas of the brain and measure the electrical activity in these areas. They then have to wait for an epileptic seizure to occur under observation. During this waiting period in the hospital, the Collaborative Research Centre team invites suitable patients to take part in a learning experiment.

Electrical appliances in budget hotels

To investigate the context dependence of learning and unlearning, the research team came up with the following story: Backpacker Nina is visiting various countries. As she has little money, she has to spend the night in cheap accommodation where the electrical appliances do not work very reliably. Some appliances, such as the hairdryer, washing machine, dryer, toaster and fan, are broken and give Nina an electric shock, causing her to let out a loud scream. The scream represents an aversive stimulus for the subjects. The sequence of one of four typical holiday landscapes, the electrical appliances and Nina’s reaction is shown 16 times in the learning phase of the experiment so that the subjects quickly learn which of the appliances are faulty and cause an electric shock.

In the second phase of the experiment, the extinction phase, some of the appliances that were previously unsafe are now safe: Two out of three electrical appliances do not give Nina an electric shock. The subjects are once again shown the landscape and electrical appliance 16 times and are asked whether they expect the appliance to be safe or unsafe. This causes them to relearn and finally know which of the appliances is safe.

In the third phase, new contexts are shown and the subjects are once again asked whether or not they expect an appliance to be faulty. “If the hairdryer was always broken during the initial learning, but always safe during extinction learning, people were uncertain whether it would be broken during this phase,“ says Nikolai Axmacher about the observations so far. As a result, there remained uncertainty regarding hairdryers, which the researchers wanted to better understand using the measurements in the brain.

Similarity of contexts could play a role

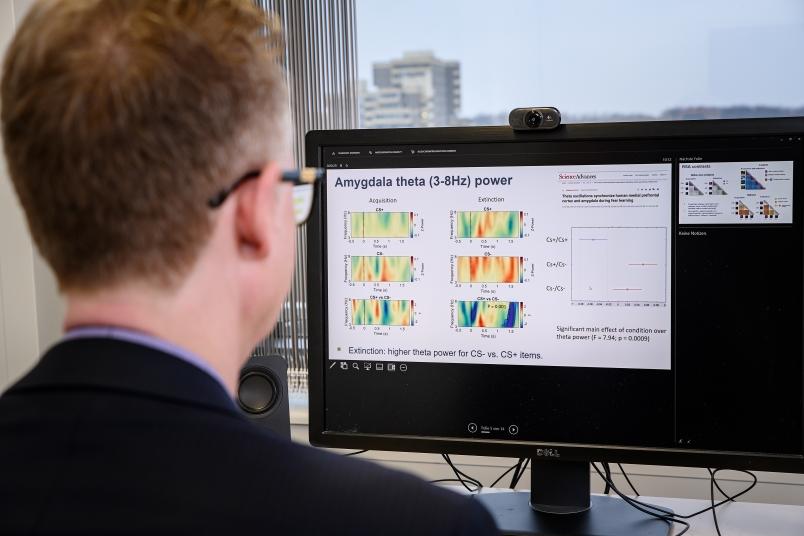

During the three phases of the experiment, the researchers observed which areas of the brain show changes in electric activity. “We have now been able to include 50 subjects in the study,“ reports Nikolai Axmacher. “Two regions of the brain, the amygdala and the hippocampus, are of particular interest to us because they are significantly involved in storing memory content. This is why we have primarily included people in the study whose electrodes are implanted in these areas of the brain.“ Although the results have not yet been evaluated in full and are thus still provisional, the research team was surprised that the amygdala did not show increased activity during the initial learning. This conflicts with similar experiments in animals in which increased activity in the amygdala was observed.

Given the importance of context, the researchers are evaluating activity patterns while various travel landscapes are being viewed. “Our hypothesis is that it depends on the similarity of the contexts,“ explains Axmacher. “If the landscape viewed is similar to one in which the hairdryer was always broken, you also expect it to be broken now. If the landscape is similar to one in which the dryer was in working order, you expect that now too.“

If this hypothesis were to be confirmed, it would mean that as many contexts as possible should be taken into account when treating phobias. If the patient learns in the cellar with the therapist that a spider is harmless, they can perhaps also encounter it in the garage without being afraid.