Report

Electric Shocks, Cold Sweats, and a Treadmill Fiasco

Contrary to popular opinion, stress can have a positive effect on learning. What is crucial is the time at which we experience it.

My calf twitches – an electric shock. I could see it coming and was already afraid. I can’t escape, my calf and my hand are wired up, my chin and forehead lie in a head rest, my eyes can only look at a monitor. What have I got myself into?

When the topics for this issue of the science magazine Rubin were shared among the members of the editorial team, I impulsively called out “Here!” when it came to who wanted to report on the research project by Dr. Valerie Jentsch and her PhD student Lianne Wolsink. And then also offered myself as a guinea pig to experience up close what awaits the participants during the experiment.

Valerie Jentsch is a stress researcher at the Department of Cognitive Psychology at Ruhr University Bochum and project manager in the Collaborative Research Center 1280. In her current project, she is investigating how stress affects extinction learning. What we already know: Stress impairs memory retrieval. However, contrary to what you might think, the effect of stress on memory isn’t purely negative.

What Jentsch and other researchers have discovered: “It very much depends on at what time we experience the stress. If we experience stress before an exam, for example, this tends to impair our performance in the exam, some of us even have the typical blackout. But if we experience stress shortly after the initial learning experience, it can even strengthen the memory trace of what has already been learned, enabling us to better retrieve this newly acquired knowledge at a later point in time,” explains Jentsch.

In her current research project, the researcher, together with her PhD student, is investigating whether intensive exercise – during which the stress hormone cortisol is released – has the same effect on extinction learning as stress. “This would be very helpful, especially in view of a subsequent clinical application within behavior therapy,” says Jentsch. Instead of subjecting patients, who are already not doing well, to an additional psychologically stressful situation, the same physiological effect could be achieved through a much more positively accepted exercise session.

I’ll also have to exercise in a bit, Valerie Jentsch has already told me. OK, sport is fundamentally healthy and I do too little of it anyway. I’ll see later on: This is precisely what will be my undoing. When I entered the simply furnished laboratory earlier with our photographer, I was not fully aware of what would await me. Valerie had asked me to sit at the table at the front, and explained the procedure to me while she attached electrodes to my left calf and my left hand.

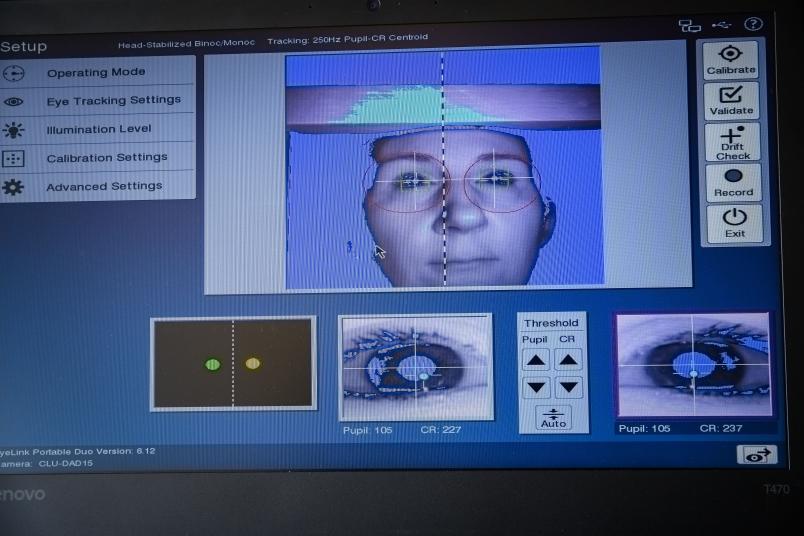

Lianne Wolsink now measures my skin conductance via the electrode on my hand. In plain language: She sees in black and white how I break out in a cold sweat. This is actually caused by the electrodes on my leg: They deliver brief electric shocks to me. My task: While my head is fixed in place with chin and forehead supports, I look straight ahead at the monitor. My pupils are filmed and Lianne can see on her monitor how they dilate or constrict during the experiment. This, too, is a response by the body to fear.

On my monitor, I am shown an image of an office in which there is a desk lamp. This is the neutral stimulus. Sometimes the lamp lights up yellow, sometimes blue. The catch: Yellow is sometimes followed by a short, harmless electric shock (we determined my pain threshold beforehand – after all, no one should leave the laboratory with a barbecued leg).

What I experience here is classical fear conditioning. And it works incredibly well. After just a short time, everything in me tenses up when the lamp lights up yellow. Will the light once again be followed by the nasty electric shock? I notice myself that my hand is getting sweaty, I don’t have to look at the curve on Lianne’s monitor to see that.

As we know, you should always get out while the going’s good. And I think this experience is now enough for me to get an initial impression. Valerie Jentsch takes pity on me and we agree to move on to the next section. One thing first: I’m not running through the whole experiment like the participants usually do, but only experiencing two excerpts. The participants actually have to come to the laboratory for three days.

Experiment procedure

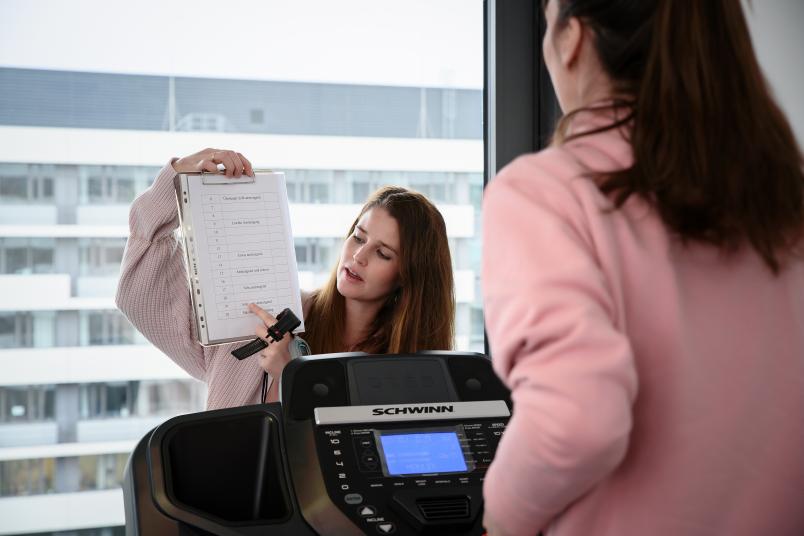

The second section takes me into another room. There is a treadmill. Before doing my sports session on it, I provide a saliva sample. This is used to measure the level of the stress hormone cortisol. “Exercise can relieve chronic stress. Exercise itself is also a stressor, namely a physical one. When I exercise at a certain intensity, my stress hormones increase. My sympathetic nervous system is activated, my heart beats faster, my bronchia expand, and cortisol is released,” explains Valerie Jentsch.

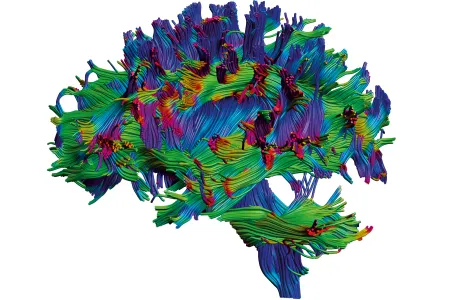

The hormone can directly pass through the blood-brain barrier and bind to receptors in the brain, whereby the excitability of the brain cells is changed. Among other places, in regions of the brain that are particularly important for our memory. This is why stress has an influence on learning and memory.

Up onto the treadmill

We get started on the treadmill. Without vanity, I can say: Based on my outward appearance, most people tend to think I look quite sporty. But how wrong they are! I have approximately zero fitness. I’ve never liked jogging. Valerie Jentsch quickly increases the speed. I’m supposed to run fast for 15 minutes. Seriously? After five minutes I’m reaching my limits. After seven minutes I stop. Judging by my breathing, I’ve covered 42 kilometers. OK, let’s not talk about it.

“When it comes to the real participants, we don’t test anyone who doesn’t exercise at all,” explains Valerie Jentsch, smirking. I would say that’s a wise decision. Once I’ve got my breath back, we go to the scientist’s office, and she tells me more about the links between stress, sport, and extinction memory.

What particularly interests the researcher is how extinction learning can be strengthened and also how it can be made more independent from the context. “Extinction learning is extremely context-dependent. This means that a patient who has learned, for instance, to no longer be afraid of dogs during behavior therapy in a practice is quite likely to still experience their old fear outside of the practice premises, i.e., in a different context. We want to find out what we can do to increase the persistence of the extinction memory and how we can disconnect it from the context of the learning situation,” explains Valerie Jentsch.

Help for patients with anxiety disorders

The results of her research show: “If we stress the participant after extinction learning, it helps them to better retrieve the extinction memory, but only in the context in which they learned it. However, if we stress the participants before extinction learning, it leads to better extinction retrieval independent of the context. That’s what we want.” It thus crucially depends on at what time the participants, or later the patients, are exposed to the stressor.

The results from the current project also show that exercise can bring about the same effects on extinction learning as psychosocial stress. However, unlike stress, which is usually associated with negative emotions, exercise tends to be associated with positive emotions. This is important if you want to translate the findings that you have obtained in the lab to the clinic.

However, it is uncertain when exercise interventions will in fact be implemented in clinical setting. “We have to be clear that we are doing basic research here,” says Valerie Jentsch. “However, the step towards clinical applications is not infinitely large.” And it is particularly the fact that her work once could also benefit patients suffering from anxiety disorders that motivates the scientist in her research every day.