Pigeons provide researchers with many insights into learning and thinking.

Knowledge Bites Why Can You Learn About the Human Brain with Pigeons?

The birds are an integral part of research. They provide many insights into how learning and memory work.

They are among the most important employees in the Department of Biopsychology at Ruhr University Bochum: Pigeons! Professor Onur Güntürkün and his human colleagues have been using birds for decades to find out how memory, learning, and the brain generally work. But why them? As birds, aren’t they evolutionary far too distant from mammals and thus from humans to be able to draw conclusions about our behavior?

Identifying core mechanisms of learning and thinking

“The fact that birds have undergone evolution separately for over 300 million years, that they have a completely differently structured brain, is of benefit to us,” explains Onur Güntürkün. “It is even a strategy in science to take a model that is completely different to humans. We are studying: Where are the similarities? Where are the differences? In this way, we can identify core mechanisms of learning and thinking that correspond to both species. And then we’ll look even further: Do they also exist in octopuses and bees?” says the biopsychologist.

Pigeons are uncomplicated animals

The pigeon also offers many other advantages. They are very tame, rarely react aggressively, and can easily be touched by trusted people. Pigeons also have a tremendous ability to learn and an unusual tolerance to frustration. They can reliably work on a cognitively demanding task for several hours uninterrupted and are not offended if it doesn’t work for a while.

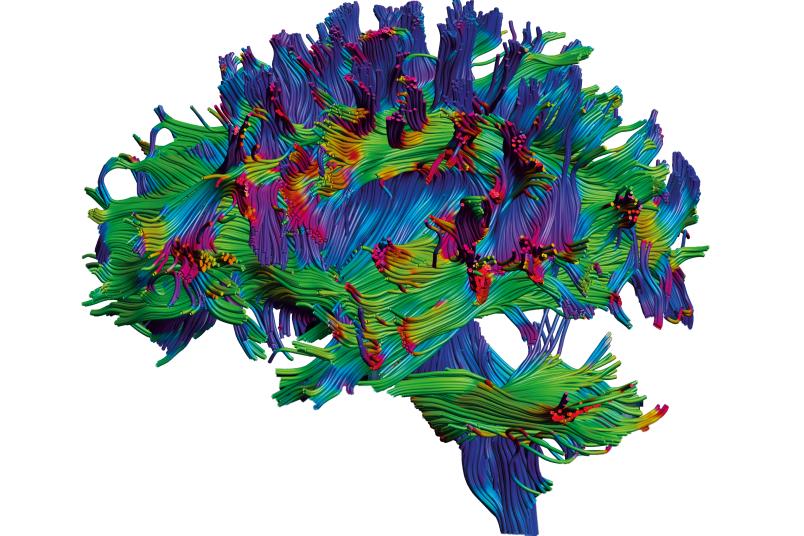

Pigeons have a highly developed visual system

And there’s another thing that sets them apart: “Like most birds, pigeons have a highly developed visual system. Their retina sends information to other regions of the brain via two to three million nerve fibers,” explains Onur Güntürkün. As a comparison: Humans only have around one million nerve fibers per eye. Consequently, a very large proportion of the pigeon brain is occupied with processing visual information. The visual long-term memory of pigeons actually comprises hundreds of images, which they can still remember years later. For instance, they can distinguish between paintings by Monet and Picasso based on stylistic features.

And, last but not least: “We are, after all, conducting research in the heart of the Ruhr area,” says Onur Güntürkün with a wink. What animal represents this region better than the pigeon? It used to be the poor man’s racehorse. And, like the Ruhr area has undergone a structural transformation, pigeons now work at the university. That makes sense, right?