In order to determine which markers point to memories experienced first-hand, the researchers devised several scenarios involving the misfortunes of a grandmother accompanied by her grandson.

Philosophy

Hidden Messages

Our choice of words often reveals more than we realize – for example, about whether we have experienced what we are talking about first-hand or not.

‘Mia stopped drinking coffee.' A simple statement. And yet, this sentence can be used to communicate so much more. Not only do we learn that Mia does not currently drink coffee, but also that she used to drink coffee. Depending on who utters this sentence and how, it can also mean that the fact that Mia does not drink coffee might be a problem. Perhaps because there is only coffee in the house. Alternatively, it could be interpreted as Mia following a healthier lifestyle by giving up coffee.

“Up until some ten or 15 years ago, philosophical models of communication were still based on the assumption that communication involves exactly one speaker and one hearer. These models assume that the two would be perfectly rational and fully attentive, would strive to increase their shared knowledge, and would literally say what they mean. But this isn’t realistic,” believes Professor Kristina Liefke. She is Junior Professor of Philosophy of Information and Communication at Ruhr University Bochum.

Listeners are very much attuned to subtle clues

Within the research unit “Constructing scenarios of the past: A new framework in episodic memory” (FOR 2812), Kristina Liefke and her colleagues are analyzing information that is indirectly communicated, but not directly expressed in a statement. Their research focuses on memory reports. “We argue that language has certain markers that indicate whether a person is reporting an event that they’ve experienced first-hand or observed as an eyewitness, or whether they’re retelling something they’ve been told in the first place,” outlines the researcher.

The word ‘how’ figures prominently in this list of markers. “Let’s say I was on vacation last year and watched my grandmother swim in the sea,” illustrates doctoral student Emil Eva Rosina. “It’s likely that I would report the event of Grandma's swimming by saying: ‘I remember Grandma swimming in the sea’.” "In contrast, a person who’s only been told about Grandma's swimming after the event occurred would be more likely to use the word ‘that’ and say: ‘I remember that Grandma swam in the sea’.” Listeners are very much attuned to such subtle clues.

Grandma's run of bad luck

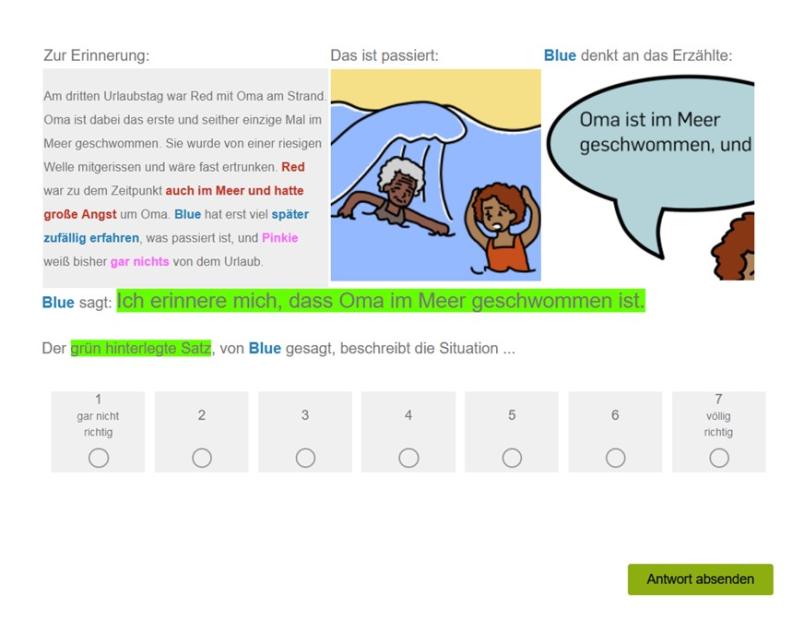

For Liefke and Rosina, sentences with the German equivalents of ‘how’ versus ‘that’ and with the English ‘-ing’ form versus ‘that’ are minimal pairs that easily lend themselves for further analysis. Faced with an unclear data situation, Liefke and Rosina conducted their own online study with 60 participants. To this end, they devised two teenage cousins, Red and Blue. Red had been on vacation with their grandmother two years previously. Blue did not come along, and was only told about the vacation's events much later. The participants in the study were each shown pictures of different events that Grandma and Red had experienced on their vacation: Grandma’s handbag was snatched, she broke her leg, she fell overboard while canoeing – in short, she had a streak of bad luck. In order to describe this to the participants, the researchers used a verbal report for each scene that reflected the way either Red or Blue would recall it. For example, for Red, this report would be, ‘I remember how Grandma broke her leg.’ On a seven-point scale, the participants rated how plausible it was that the person in question would phrase the sentence like this.

In the study, the researchers showed the participants scenes from the vacation of an elderly grandmother and her grandchildren. The scenes were captioned either by a statement from the grandson who accompanied her or by a statement from another grandson who didn’t accompany her.

Study participants were instructed to judge the plausibility of each statement.

The evaluation clearly shows that the marker ‘how’ indicates that a person is remembering something that they experienced first-hand. The study participants considered it plausible that Red recounted the events in this way, but implausible that Blue did – unless 'how' was understood as 'the way in which'. For Blue, who had not been there herself, they found the use of ’that’ more likely: She remembers that Grandma broke her leg.

“However, choosing ‘how’ in a memory report is not sufficient to conclude that someone has in fact experienced something that they are recounting,” stresses Kristina Liefke. The researcher bases this assessment on an analysis of participants' rating of the statements made by yet another character created for the study: Goldie. Although Goldie was not directly present at any of Grandma’s accidents, she arrived shortly afterwards and witnessed direct evidence for the event – Grandma limping after breaking her leg, for example, or smoke coming from the kitchen after Grandma had burned a cake. “When attributed to Goldie, statements with the marker ‘how’ (’I remember how grandma broke her leg’) were rated very inconsistently as plausible or implausible,” explains Kristina Liefke. This suggests that different listeners have different criteria for what they consider a personal experience of an event or direct evidence for it.

Kristina Liefke (left) and Emil Eva Rosina hope to bring order to the chaos that is language.

Beyond German ‘wie’ (’how’) and the English ‘-ing’ form, the researchers expect a large number of other markers for personal experience, which they are exploring in current and follow-up studies. These markers include emotional interjections – for example 'brrr' in ’I remember how I was swimming in the sea that day – brrr, the water was cold!' Switching to present tense in a narration that started in past tense can also be an indicator. Likewise, perception verbs can be used as indicators, as in ’and then I saw/heard...’.

Perspectives and narrative times

The perspective from which an experience is reported can reveal various interesting pieces of information. However, this perspective doesn’t always have to be 'own eyes' (such that it captures a first-person point of view). “People who recall a traumatic event often use the neutral pronoun 'one', an impersonal form of ’you’," explains Kristina Liefke. “The memory thus takes a third person perspective’: People watch themselves acting in their memory recall of the event, so to speak.”

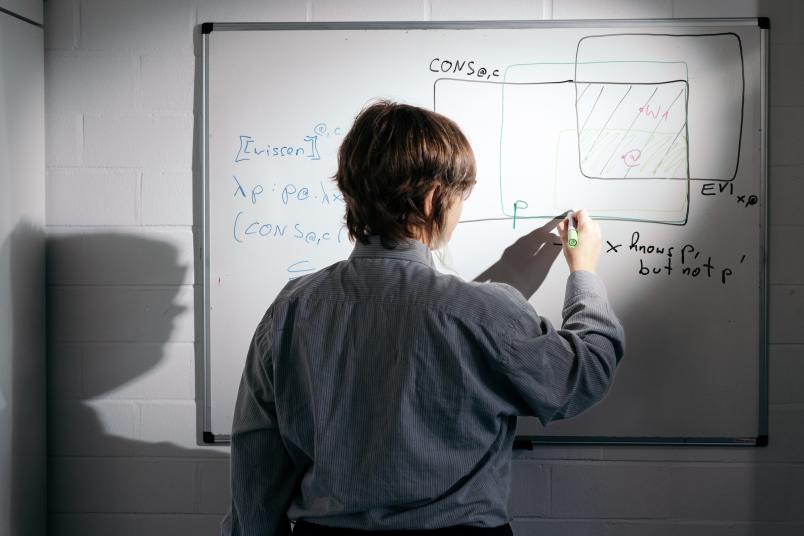

The diagram illustrates the formal modeling of the meaning contributed to the phrase ’noch wissen’ (still know/remember). The modeling is done in a logical language that has many elements in common with the Haskell programming language.

“Language is one big mess and we’re trying to bring some order into this chaos,” says Emil Eva Rosina. But they believe that their research has not yet reached the application stage. “People often ask us if our findings can be used in court to determine whether or not a witness testimony reflects what someone experienced first-hand,” they say. “But it’s not that simple.”

Or at least not always. The researchers have identified a surprisingly revealing insight about the use of the phrase “I remember” or, as it’s often phrased in German, “I still know”: Contrary to what one might expect, speakers use such memory predicates mainly when they are unsure, or when they do not trust their own memory. Otherwise, they simply report the event. People who say ’I remember being on the train’ often continue their story by saying something like ’but I don’t quite remember where I was going’.