Medicine

Mysteries between Light and Liver

People who work against their internal clock over a long period of time increase the risk of fatty liver. The correlations are complex, but one research team in Bochum is trying to get to the bottom of the issue.

“Artificial light is making us sick,” says Professor Mustafa Özçürümez. It allows us to turn night into day. We stay awake and eat late, sleep irregular hours, and mainly stay indoors. All of this derails our entire metabolism. In the worst case, if we disregard our internal clock for years or decades, this can lead to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (formerly non-alcoholic fatty liver disease). “Shift workers often suffer from this disease, as do blind persons who can’t take in light through their eyes,” says Özçürümez, who leads the Medical Laboratory unit, which is a section within the Department Internal Medicine at the Knappschaft Kliniken University Hospital Bochum.

Mustafa Özçürümez, Jasmin Weninger, and Abdurrahman Coskun (from left) are working together on the connection between light and the liver.

Together with Dr. Jasmin Weninger and Professor Abdurrahman Coskun, Özçürümez is investigating the underlying correlations. Through various studies, the researchers are investigating the finely tuned control loop of our day-night rhythm, also known as our circadian rhythm, and the factors that disrupt it. One major cog in the entire system is the hormone melatonin. “Melatonin is released when it gets dark,“ explains Özçürümez. “It makes us tired and helps us get a restful sleep.” It also has other important functions that aid in regeneration, and it influences the liver, too.

Even the light of the full moon disrupts melatonin secretion

There are indications that melatonin protects the liver, such as in patients who have to take certain lipid lowering drugs,” says Özçürümez. “Additional doses of melatonin alleviate the side-effects on the liver caused by the medication, presumably due to melatonin’s antioxidative and anti-inflammatory characteristics.”

One problem: Artificial blue light, such as that emitted by mobile phones, computers, televisions, and streetlights, makes it difficult to experience true darkness. “Even at ten lux, which is the light emitted at night during a full moon, it is more difficult for the body to produce melatonin,” warns the lab physician.

Our internal clock is influenced by a range of other factors as well. Genetics determine whether we are early risers or night owls, but our sleeping and eating habits, and the lighting we are exposed to, play a critical role. The latter does not even necessarily have to be visible light: Certain photoreceptors in the eye directly and indirectly send signals of non-visible light to our central internal clock and organ-specific rhythms. This complex interaction is prone to disorders that can have drastic consequences.

The complexity is illustrated by the observation that melatonin is produced not only in the pineal gland, but also in the intestine. Our intestine is subject to a circadian rhythm that plays a major role in controlling the liver’s metabolism.

To examine the correlation between chronotype, i.e. the individual configuration of our internal clock, and diseases of the liver, the team in Bochum, for instance, researches the activity of “clock genes” in hair root samples and measures melatonin production in parallel. “We’re essentially examining early risers, night owls, and the people in the middle,” explains Özçürümez. These and other tests can very reliably identify the chronotype in order to study the correlation with other liver diseases.

Lark, owl, or dove?

“Early birds have the healthiest lifestyle,” explains Özçürümez. This is because they most closely adhere to the natural rhythms of our ancestors, going to sleep and waking up early without artificial lighting. “Back then, there was nothing left to do when it got dark outside. You would have been prey.” Now, light pollution, blue light from our phones in the evening as we lie in bed, or late evenings on the weekend are artificially making our days longer, with the result that many people sleep in the next morning. The scientists refer to the resulting sensation as “social jetlag,” a permanent mini-delay that harms our health.

Sleep disorders are not normal

“The spectrum of biorhythm disorders is incredibly vast,” Weninger emphasizes. “On top of that, sleeping problems are often viewed as normal or personal matters and aren’t seen as an illness.” Yet these factors that bring our biorhythm out of balance have far-reaching consequences for our overall health. If our internal clock is altered or postponed into the evening hours, this increases the risk of sugar metabolism disorders, which can lead to fatty liver over time. “Fatty liver is a disease with many causes and it develops over years or even decades,” says Özçürümez.

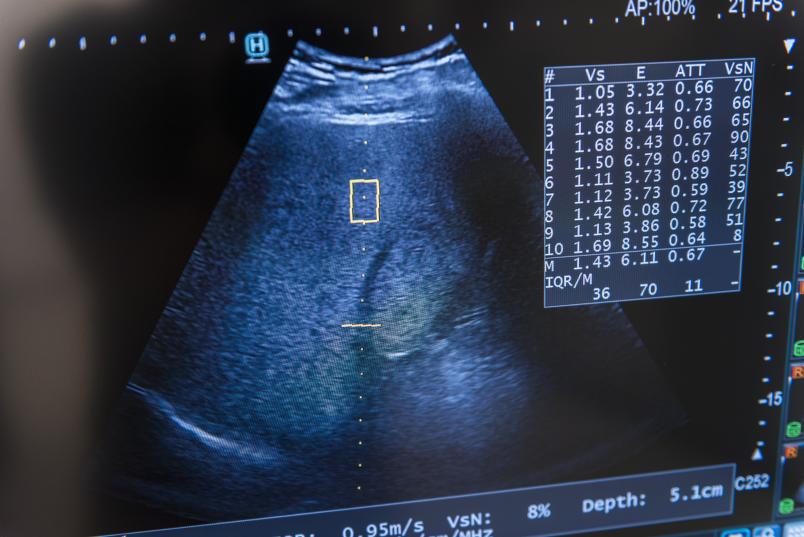

Evaluation of movement and sleep data from a special measuring device used in the study on patients with fatty liver disease.

A different, ongoing study for which participants are still being sought seeks to investigate what exactly happens in the body depending on how we shape our day. The team is putting in great effort to assess the biorhythm of subjects with and without fatty liver disease. The subjects spend one night at the hospital. Over 24 hours, blood pressure and body temperature are continuously recorded and blood and saliva samples are taken at different times to measure melatonin and other values. In addition, the subjects periodically fill out questionnaires on their activities, sleeping habits, and times outdoors and indoors. Following their night at the hospital, they wear light sensors (light-dosimeters) for two weeks. These sensors precisely document how much light, both artificial and natural, reaches the eyes at which points throughout the day. “The subjects learn a lot about themselves,” says Özçürümez. They are compensated for their participation and, following the study, receive a detailed report on their chronotype and numerous other results from the experiment.

In order to better evaluate the processes in the liver, the team has developed an experiment setting in which pig liver can be artificially maintained outside the body in a nutrient solution, allowing them to study metabolic processes under controlled conditions. Abdurrahman Coskun has patented such a solution that can be used to continuously flush the organs. Over 24 hours, Jasmin Weninger takes samples in four-hour increments to examine genetic activities in the liver. The primary emphasis is on the clock genes that determine circadian rhythms. “By isolating the corresponding RNA every four hours, we can prove that the main genes retain their rhythm under the conditions of the experiment,” says Weninger. “One third of the genes in the liver are subject to a circadian expression that indicates comprehensive regulation by the internal clock.”

The experiment will then undergo fine-tuning with temperature-, pressure-, and nutrient-controlled day cycles, realistic conditions as can be found within the living body. The goal is to keep the liver alive for over 24 hours in order to identify the exact biological control loops between light and the liver.

How prevention could succeed

"Only few research groups worldwide are working on this, and there are still many more questions than answers", says Özçürümez. If the influence of the chronotype on the development of fatty liver disease can be proven, this would have major consequences for prevention. The use of light therapy, such as in polar regions, glasses with blue light filters, melatonin compounds, and behavioral therapy for improving sleep could become more important.

The origin of the internal clock