Chemistry Tracking a solvation process step by step

Numerous chemical and industrial processes take place in solution. But the exact interactions between solvent and solute are not yet understood.

Chemists of Ruhr-Universität Bochum tracked with unprecedented spatial resolution how individual water molecules attach to an organic molecule. They used low-temperature scanning tunneling microscopy to visualize the processes at a scale smaller than one nanometre. This allowed them to investigate the phenomena of hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity at the molecular level, i.e. why certain parts of organic molecules attract or repel water.

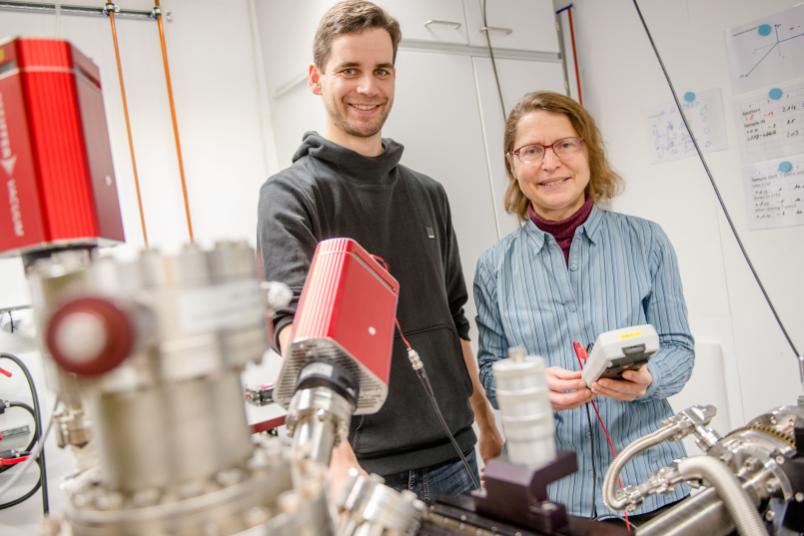

“The results are an important step on the path to understanding solvation processes, that is, how substances dissolve in water”, explains Karsten Lucht of the Bochum Chair of Physical Chemistry I. He reports the results with the team led by Prof Dr Karina Morgenstern and colleagues from the Chair of Organic Chemistry II in the journal “Angewandte Chemie”. The scientists cooperate in the excellence cluster Ruhr Explores Solvation, or Resolv for short.

The aim of the cluster is to understand how solvents affect the reactions in solution and the use of solvents to control reactions.

Tracking water accumulation step by step

As an organic molecule, the researchers used an azo dye that consists of two carbon rings with attached functional groups that are polar, i.e. slightly positively or negatively charged. They deposited the molecules on a gold single crystal and cooled the system to six Kelvin. Then they added individual water molecules step by step and observed where these attached to the dye.

The first water molecules preferred to attach themselves to the polar functional groups. When the researchers increased the amount of water, the newly added molecules attached themselves to the water molecules that were already bonded. “Our experiments show that hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity can be traced back to molecular level”, says Karina Morgenstern. The water molecules avoided non-polar areas of the molecule, polar areas were preferred.

Three complementary procedures

The processes that were observed here with scanning tunneling microscopy are usually investigated spectroscopically or with molecular dynamic simulations. However, the first method does not provide spatial information, and the latter is based on assumptions due to the size of the system. “Every method has its value”, explains Karsten Lucht. “The three approaches complement each other.”