Neuroscience How the brain might compensate stress during learning

Friend or foe, chequered or striped – the brain divides everything around us in categories. How the brain manages this task under pressure.

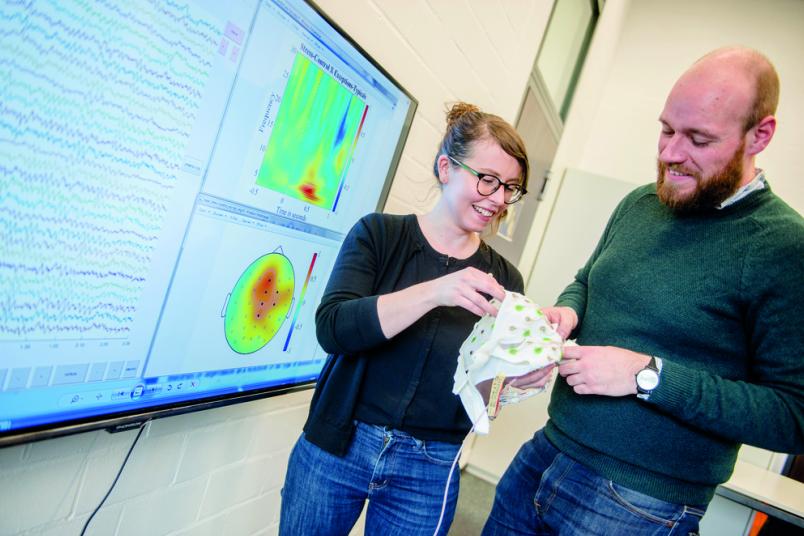

When people have to assess a situation within seconds, it helps them to draw on learned categories. Psychologists from the Ruhr-Universität Bochum examined with the help of electroencephalography (EEG) how well category-learning works in a stressful episode. They published their research on a mechanism, the brain may compensate stress with, in the “Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience”.

Prof Dr Oliver Wolf, Prof Dr Nikolai Axmacher and Prof Dr Boris Suchan from the Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience in Bochum joined their forces to conduct this study.

Ice water and a camera trigger stress

The scientists compared the performance of 16 stressed men with the performance of 16 relaxed men in categorisation learning. Half of the participants had to put their hands in ice water and were filmed, before they took the learning test – an accepted stress-test. The other half had to put their hand in warm water, without being filmed. “We decided to design our study with men only for now, because women tend to react differently to stress during their hormone-cycle,” says Marcus Paul, one of the authors.

During the test the participants had to divide different coloured rings by means of their colour scheme in two categories. They not only had to learn to assign typical objects, but also exceptions – rings, which differed from other rings in their category. Previous studies have shown that the brain regions that are crucial for learning exceptions are particularly sensitive to stress. During the test, the scientists measured the brain activity of the participants by EEG.

Different brain activity under stress

The stressed participants performed as well as the relaxed ones in the categorisation-test. But their brains showed an increased activity during the test and they used additional brain regions. The EEG of the stressed participants revealed increased activity in the theta-frequency above the medial prefrontal cortex, particularly when the participants learned the exceptions. Theta-waves reflect cognitive control mechanisms.

“We think, we have found a mechanism which allows us to give a good performance in a categorisation-test, even if we are stressed”, says Oliver Wolf.

In the next step the scientists from Bochum intend to analyse, whether the change in the neuronal activity of stressed and relaxed participants during the learning process affects their performance in a test conducted on the following day.