Linguistics

This is how we understand emoji

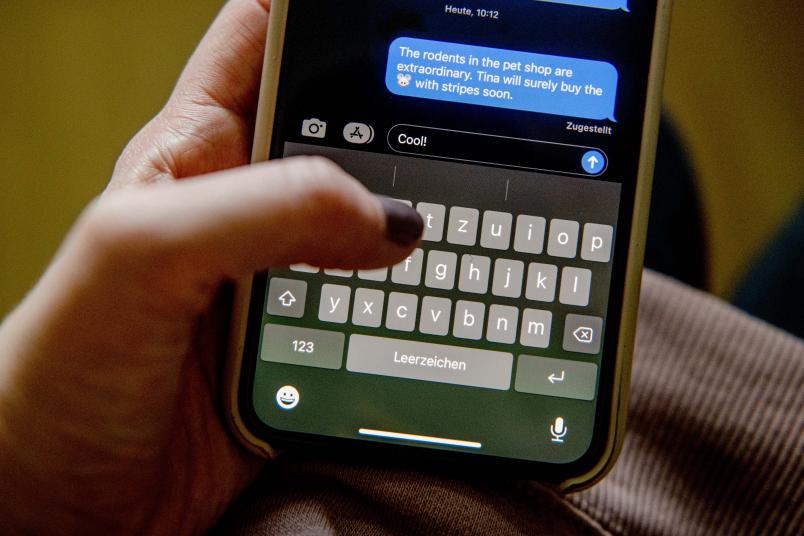

If a word in a sentence is replaced by an image, we still understand its meaning. But the detour via the image can take time.

Even when emoji are used to substitute for words, we still understand the sentence. But how does that work? Do we interpret an emoji primarily as an image or as a word? To find out, a research team from Bochum, Potsdam and Berlin asked volunteers to read texts with emoji and measured the reading time precisely. It turns out that it takes a little longer to comprehend a sentence that includes emoji than one that doesn’t. If the emoji does not directly represent the intended meaning, but another word with the same pronunciation, we need yet a little more time. Based on these results, the team concludes that emoji comprehension consists of two steps: first the image is interpreted, then the word is inferred. The study was published in Computers in Human Behavior on 25. October 2021.

The study was carried out in a collaboration between Prof. Dr. Tatjana Scheffler, assistant professor for Digital Forensic Linguistics at the German Studies Institute at Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB), and colleagues from the University of Potsdam and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

A knight in the night

Emoji are small image icons that originated in Japan: Japanese “e” means picture, “moji” means word. “We set out to explore to what extent reading emoji is more similar to reading words or interpreting pictures,” explains Tatjana Scheffler. To this end, the researchers conducted an online study where participants read sentences in which some words were replaced by emoji, and measured the reading time for each word. Subsequently, they asked questions to test whether the participants understood the sentences.

“As we had suspected and as other studies suggest, our participants easily understood sentences with emoji instead of nouns,” the researcher points out. The comprehension questions were even answered correctly slightly more often – but not significantly so – following the sentences containing emoji than following the same sentences without any emoji.

Normal words, however, do not only lead to the meaning while they are being processed; they also have other properties that are activated during reading: for example their pronunciation. And words can be homophones: when two words have the same pronunciation but different meanings, for example like the knight and the night. The researchers wanted to find out if emoji can also trigger this phenomenon. “Therefore, we had our test participants read sentences in which the emoji doesn’t show the intended object but its homophone,” Tatjana Scheffler explains.

“We showed that the sentences were almost always understood correctly, even when homophones were used,” points out Tatjana Scheffler. “This indicates that an emoji can be broken down into a complete ‘lexicon entry’ that contains information about its pronunciation. Based on this information, the participants then derive the other, homophonic meaning.”

Still, the team also showed that the reading times differed considerably. The average reading time for a written-out word is approximately 450 milliseconds, for a corresponding emoji approx. 800 milliseconds and for an emoji depicting a homophone more than 900 milliseconds.

A detour via the image takes time

This leads the researchers to conclude that the image must be interpreted first when reading emoji. Emoji are generally less recognisable and more unusual, and therefore not as easy to read as written words. “This is also supported by the fact that those test participants who self-assessed as using emoji often, read matching emoji more quickly,” Tatjana Scheffler explains. Since readers can also derive a pronunciation for emoji just like for words, homophone emoji are also readily understood. This takes longer, however, because the visual information has to be suppressed and the meaning of the homophonic word has to be recalled. “In this case, the fact that someone is used to emoji is no longer helpful. Participants who use emoji more often read the homophone emoji just as slowly as the others,” Tatjana Scheffler concludes.

Together with the team at Charité, she plans to conduct a similar study with people living with schizophrenia. Since some of them have difficulty identifying non-literal meanings, a comparison with a control group should provide additional insight into language processing, the linguistic structure of non-literal meaning and the linguistic effects of schizophrenia.