Media Studies

Witness report from a fridge

Professional forensic investigators can tell a lot from digital data footprints. But they’re not the only ones.

Smart toothbrushes, light bulbs and fitness watches, connected garage doors and front doors with video recognition systems, personalised social media profiles and streaming accounts – we leave digital footprints wherever we go in our everyday life. The same goes for criminal offenders – to the delight of professional forensic experts, who now have a fleet of high-tech instruments and computer processes at their disposal for investigating these new media crime scenes. In his book “Medien der Forensik”, Professor Simon Rothöhler outlines how such methods work. In addition, the media scholar also looks into popular forensic methods. Rubin, the RUB’s science magazine, features an article about his research.

Media play a role at various points in forensic investigations: from the moment professionals enter a crime scene, to the examination of samples in laboratories, to the appearances of forensic experts in court. “Forensics as an institutional practice is built around the investigation of trace evidence. This means that the trace is at the heart of it,” says Simon Rothöhler. Blood, hair, saliva residues, tyre marks – there is a multitude of material traces and, consequently, just as many areas of expertise. “Media technology didn’t appear until quite recently in this list as an explicit field of expertise,” explains the media scholar.

[einzelbild: 2]

Digital traces

Digitalisation was the game changer. This is because the digitalisation of everyday life produces an enormous output of digital traces and data. Rothöhler is referring primarily to devices that aren’t conventional surveillance systems, such as smartphones or even smart fridges. All these devices have network access and store data that can in turn be read out by forensic means. And indeed, there have been cases where forensic investigators were able to apprehend and ultimately convict a murderer with the help of the sensors of a smart fridge.

A new approach to media forensic investigations

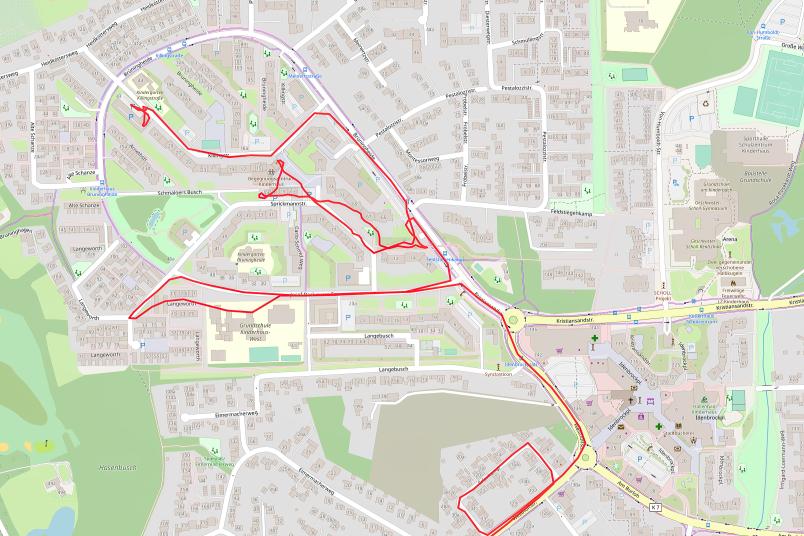

Inevitably, digitalisation has not only stepped up the volume of evidence; it has also changed the way forensic information is gathered by the investigating authorities, providing for new areas of application and more complex forms of evidence recovery. In order to determine whether digital image, audio or video material is genuine, media forensic experts today have to scrutinise the metadata and pixel structures for disturbances, manipulations and suspicious structures. In order to trace and decode the complex data and digital transport routes, forensic investigators are relying to an increasing extent on computer-aided tools and highly specific software. This applies, for example, to the field of crime scene photography. “Forensic investigators today use 3D laser scanners to measure rooms and thus freeze the crime scene visually. Eventually, the crime scene is virtually modelled and can be walked through,” elaborates Rothöhler. Digital media also present a number of challenges for institutional forensics, for example when it comes to the question of where data that has been stored in the cloud is physically located or how to get at data that is located on servers outside Europe.

Forensics in popular culture

In his book, Rothöhler speaks of a popularisation of forensics. “There is clearly a history of fascination with forensics,” explains the media scholar. If you take a look at literature, films, series or podcasts, you will always come across depictions of forensic practices that resemble each other. At the same time, media forensics has also become popularised in the sense that it has become part of our everyday life in a modified form, Rothöhler argues. “Every one of us, if we get an email from an unknown source, we will almost automatically google that person’s name, identify their social media account in the search results and then check what kind of content they enjoy, what they’ve liked, shared, commented on and so on In other words, we are reading digital traces on a daily basis – just like forensic investigators.” This is also the case when we use social networks or look for restaurants or holiday destinations. All these common practices could be called paraforensics or pseudoforensics. We imitate real forensic investigators. Naturally, pathological forms exist here as well – as in the case of media-sceptical conspiracy theorists, for example.

[infobox: 1]

[infobox: 2]

[infobox: 3]