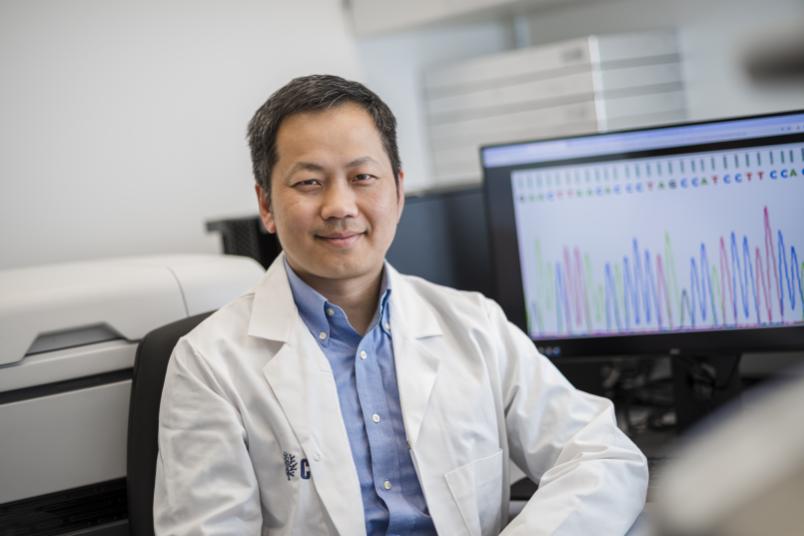

Huu Phuc Nguyen heads the Department of Human Genetics at Ruhr University Bochum.

Huntington’s disease

How Damaged Huntingtin Proteins Are Broken Down

Researchers have elucidated key steps in the ubiquitin tagging of the mutated huntingtin protein, providing hope for future therapies.

There is no known cure for Huntington's disease. A genetic mutation creates harmful proteins that accumulate and cause the disease's typical symptoms. A team from the Department of Human Genetics at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, has now shown how targeted ubiquitin tagging at two positions in the mutated huntingtin protein affects its breakdown and distribution within the cell. This insight could provide a starting point for future therapies. The team in Bochum, led by Professor Hoa Huu Phuc Nguyen, worked closely with Israeli researcher Professor Aaron Ciechanover, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 for his work on the protein degradation system. The journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reports the findings in its issue of January 8, 2026.

Harmful proteins must be eliminated

Huntington's disease is a rare but severe genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the huntingtin gene. This change results in an altered variant of the huntingtin protein encoded by the gene. “It contains extended glutamine chains that cause the protein to misfold, rendering it unable to properly perform its function,” explains Nguyen. Misfolded proteins are dangerous to the body and must be broken down. However, the mutated huntingtin protein is not removed efficiently and instead accumulates. Patients with this disease eventually experience symptoms such as movement disorders, dementia, and psychiatric abnormalities. “There is still no cure for Huntington's disease. All patients die from it at some point,” says Nguyen.

Together with his team and international partners, the human geneticist is investigating the foundations of the disease and attempting to uncover its underlying mechanisms. In their current study, the researchers took a close look at the degradation of the proteins involved. “Before a damaged or misfolded protein can be broken down, it is tagged and transported to the cell's degradation complex,” Nguyen explains. “Ubiquitin tagging at two specific positions in the huntingtin protein, K6 and K9, plays a key role in the degradation and distribution of the protein in the cell.” Once tagged, the proteins are transported to the proteasome, the cell's central protein degradation system, and eliminated.

Blocking the tagging positions worsens the disease

The researchers were able to observe this process in cell culture during a previous study. Now they have replaced the mouse huntingtin gene with a disease-causing human variant in a special knock-in mouse model. In a different mouse line, the sites K6 and K9 in the huntingtin protein were altered to prevent ubiquitin tagging. “We observed that the symptoms of Huntington's disease worsened considerably,” reports Nguyen. “Signs of the disease also manifested earlier than in mice that only carried the huntingtin mutation.”

The researchers hope that this insight will provide a basis for future therapies. “Knowing the relevant tagging sites could make it possible to stimulate the degradation of damaged huntingtin protein,” says Nguyen. “We believe that the mutated protein escapes degradation because the disease-induced structural change and disrupted ubiquitin tagging at crucial sites inhibit its breakdown.”

The Huntington Zentrum NRW