Theology

Inscribed, Buried and Cursed

In antiquity, curses carved into lead tablets were considered effective as long as they remained hidden. This practice is even referred to in the Bible.

“I don’t believe it! I left my bike here only a moment ago and now it’s gone! It’s been stolen! Curse the thief, he’s probably long gone!”

Incidents such as this can make your blood boil. And this has always been the case: Even in ancient times, people would experience helpless fury over theft, heartbreak and other circumstances outside their control. But they also had ways to deal with it. They used curses to wish misfortune on their adversaries, both known and unknown.

“In the period between around 500 BC and 500 AD, cursing was part of everyday religious practice in the Roman Empire,” explains Professor Michael Hölscher, Head of the Chair of New Testament Exegesis at the Faculty of Catholic Theology at Ruhr University Bochum. His research explores the relationship between such cursing practice and biblical texts. “Since the ritual required the curse to be inscribed, for example on a thin sheet of lead, we can still reconstruct it today.”

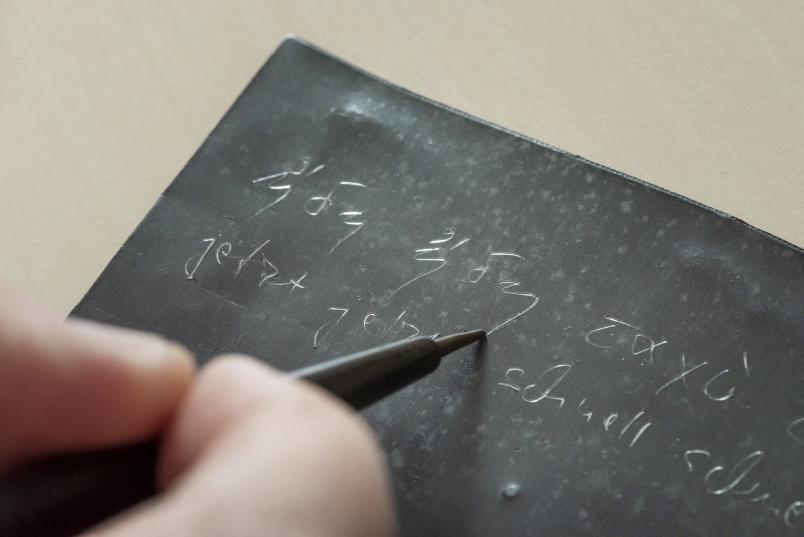

The curse had to be inscribed on the lead tablet. “While all you had to do was scratch in the name of the person you wanted to curse, the curses often included both individual and standardized wording.” says Michael Hölscher. If you didn’t know the name of the person you wanted to curse – such as the aforementioned thief – you’d paraphrase it in such a way that it would cover as many options as possible, for example by saying: “I curse the person, man or woman, soldier or civilian, free or slave, who stole my swimming trunks”. The names of gods and demons were also frequently scratched in. Instructions on how to place a curse on someone are recorded in magical papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt. Once the inscription was completed, the tablets would sometimes be rolled. People who wanted to make the curse stronger would wrap the tablet around a chicken bone as a symbol of death, pierce it repeatedly and attach a bound or pierced clay doll to it.

As long as the tablet remained in that one secret place, the curse was active.

These objects were then deposited in places where people believed the powers of the underworld to dwell: They were placed in the graves of those who had died an untimely death, buried near shrines and thrown into springs or the sea. “As long as the tablet remained in that one secret place, the curse was active,” explains Michael Hölscher. “Once it was dug up, the curse got lifted.”

Dangerous ritual

For the person placing the curse, the only instance of danger occured during the ritual of depositing it in a secret place. This is because the practice of cursing was forbidden under Roman law. “It was considered dangerous and harmful,” points out Hölscher. Still, everyone was aware of it. “Around 1,700 such tablets have been excavated, in locations ranging from Rome to Trier and from Asia Minor to Britain,” he continues. “The practice was probably spread by the Roman army.” The finds provide a great deal of information for researchers: “You can see the names people had, how much money they had, whether they were civilians or soldiers,” lists Hölscher. As far as he is concerned, however, key question is this: While it is a culture of curses, it is also a religious practice. So, how does it fit in with biblical texts?

The lead tablets were inscribed in Latin or Greek. Around 1,700 have been found so far.

“When reading the New Testament, we tend to focus on the blessings; but the Bible does also contain curses,” stresses Michael Hölscher. “One such example is Jesus cursing the fig tree.” Texts in the Bible also address the question of whether it is acceptable to curse others. “It’s about the appropriate use of language,” says Hölscher. “And the conclusion is that you should use it to bless rather than curse.”

The description of beasts

One book of the Bible that is of particular relevance to the researcher is the Book of Revelation, the final book of the New Testament. This is because several factors indicate that it was written in Asia Minor, now Turkey, at a time when the region was under Roman rule. “The Book of Revelation grapples with the Roman Empire and its claim to power and is aimed at the small Christian minority that lived in the midst of the predominantly Roman society. They had to distance themselves from this society, and the Book of Revelation does this by demonizing Roman culture,” outlines Michael Hölscher. “The official religion with its deities is depicted as magic, and anything magic was forbidden. Conversely, there is the Christian God, who is described as truly mighty and is thus exalted. According to the storyline outlined in the book, he will eventually triumph over the Roman gods: an idea that brings comfort to the oppressed minority.”

Michael Hölscher deals with everyday religious practice in antiquity.

The Book of Revelation contains several references to the widespread practice of cursing. For example, chapter 13 describes two beasts rising from the sea: “A beast rose up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns. On its horns were ten royal crowns and on its heads blasphemous names.” “The animal was described in the same way as a lead tablet,” clarifies Michael Hölscher. “In the end, both are of course defeated. We can interpret the text to mean that one beast stands for the Roman emperor and the second for those who pay homage to him. Both are depicted as subjects of Satan and are ultimately defeated by the more powerful God of the Book of Revelation.”

Roman culture and religion are thus beaten at their own game

A second example refers to the ritual of hiding and burying the curse tablets as a proxy for the cursed person. The fall of Babylon is described in chapter 18: “Then a mighty angel took up a stone like a great millstone and threw it into the sea, saying: Thus with violence the great city Babylon shall be thrown down, and shall not be found anymore.” “Babylon stands for Rome,” points out Michael Hölscher. This city is subtly associated with the cursed person in the ritual of the curse tablets. “This means that the Roman enemy is destroyed through a process that was considered magical and forbidden by official Roman authorities.” Ultimately, Roman culture and religion are thus beaten at their own game in the vision of the Book of Revelation.