Interview with the researcher The interconnectedness of writing

In our interview, American Studies scholar Laura Bieger discusses the political role of fiction, a new public sphere and the resilience of American democracy.

Politics inevitably finds its way into the works of creators of art, culture and literature. But just how political can and should fiction actually be? Professor Laura Bieger has been grappling with this question for years. She looks with concern at a country in political turmoil and is aware of a strong politicisation pressure in US society, which is not only reflected in culture and the media, but also in the critical reception of such texts. A remarkable phenomenon for Bieger is that an increasing number of authors are deliberately deciding to experiment with different text forms and platforms, to network more strongly in the media in order to negotiate, reflect and discuss political issues.

Professor Bieger, what does social cohesion mean to you?

Social cohesion is fundamentally about social relationships. Social relationships are communicated through our culture, our collective memory, our shared rituals. Through cultural practices and forms of communication, we come to an understanding and agreement on values, we appreciate them and make them public. This is how we create and communicate social cohesion, too.

As an American Studies scholar, you research culture, society and literature in the USA. You recently visited Harvard University for a research stay. How did you experience the USA, and specifically social cohesion in the USA?

As incredibly torn and polarised. This is nothing new or surprising, of course. Most recently, we witnessed it in the election of the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the deplorable state of the Republican Party and that of American democracy. News about mass shootings in high schools and supermarkets have become a staple of present day U.S. culture. Many of these shootings are blatantly and openly racist. As a scholar who studies this country and this culture, such incidents challenge you; but they also hit you on a personal level – when you are in the country while they happen, or talk to colleagues and friends.

It takes its toll on social cohesion.

Laura Bieger

Just recently I was talking to a colleague from Santa Cruz who was worried about her child because the school had been warned of a possible attack. Sadly, this has become a part of everyday life there: all that parents can do is hope that their children will make it through school in one piece. My colleague was fed up that these worries, the preoccupation with them, take up so much space and time in her life. Such things take a toll on social cohesion. But on the other hand, I find it very remarkable how much resilience there is in the country and how pragmatic Americans are in coping with the challenges.

How do authors and other culture creators react to the social and political trends in the country?

I’ve definitely been observing repercussions in literature, in the arts, as well as in the critical debate surrounding them, to become politicised. The day after Trump was elected, I thought to myself: I want my research to focus more on explicitly political issues. Contemporary literary and cultural production has seen a similar shift. So, this is a good moment to reflect on art and literature that are engaging with politics – and that traditionally haven’t enjoyed a good reputation.

Why not?

There are always discussions about the autonomy of art and what it really means. Some people think that art must be radically autonomous in order to be good art at all. In turn, this means that art that is specifically engaging with political issues can’t be good art. But art, print media and even literature have the unique capacity to stage and act out social negotiation processes, to create a kind of training ground and test environment for political processes. This is where, for example, values are negotiated on a social level. Some art forms or genres, such as political theatre or essays, seem to have more social weight and prestige than others. I think now is a good time to take a closer look at the discourse and the dichotomies, to examine forms of art and literature that are engaged in political issues, and to reflect on the role of art in the public sphere.

What have you been observing on the fictional training grounds?

One thing I find striking is that many artists make a deliberate effort to integrate their works into wider networks. Many of the contemporary writers are becoming political by pairing their fiction with journalistic and essayistic writing. They use platforms such as Twitter to reach a wider audience, and they try out other narrative media such as podcasts or films. This use of media networks is, in my opinion, quite a remarkable phenomenon.

What about all this do you find so fascinating?

I’m interested in how this web of relations between texts and other actors shapes political events. The work of art as such plays a central role, but so do the relations embedding it. What do these different media contents contribute to the division or cohesion of a society, for example? And which theoretical tools do we need, which concept of aesthetics, for example, to conceptualise the web of relations between texts? These are the questions I’m currently exploring.

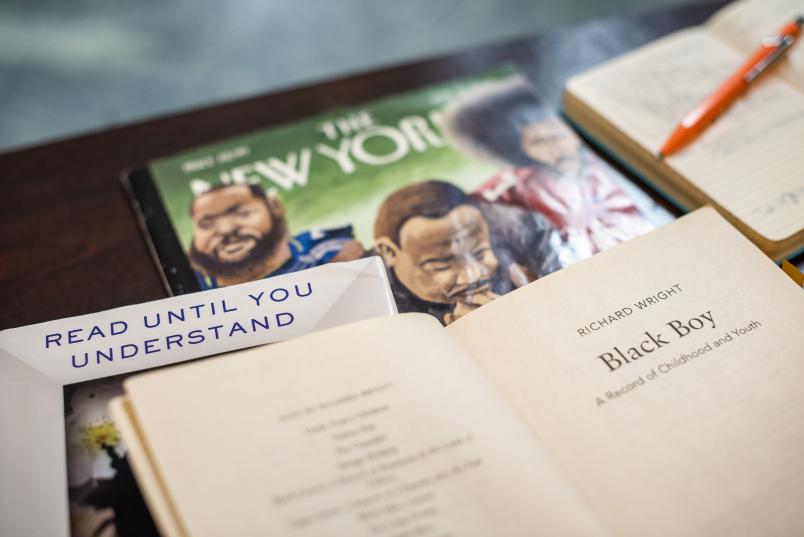

You recently studied the novel “Native Son” by the Black American author Richard Wright. How political is Wright’s writing?

Wright’s novel “Native Son” was published in 1940 and sent a shock wave through America's literary production and American society at the time. It received a great deal of publicity, stimulated debates and was incredibly controversial.

What was so unusual about the novel?

Before it was published, it would have been unthinkable to create a protagonist who was Black, a rapist and a serial killer. The author took a tremendous risk with his protagonist, “Bigger Thomas.”

What was it about the novel that interested you?

The thing I found most interesting is that the novel was so provocative that its author had to authorise it in several steps. Wright first commented on his protagonist in a separate pamphlet, which then became an epilogue and has since become the introduction to the novel. In this pamphlet with the title “How Bigger was Born,” Wright explains that the fictional protagonist of his novel is a composite of different people that he knew in real life. In other words, it feeds back to the author’s personal experience, his lived reality. The genre and the protagonist practically forced Wright to explain his work, first in the essay, and later in his autobiography, which became another bestseller.

The novel and its controversial protagonist thus come to be actors in a complex set of relations that are used to negotiate both the artistic value of the novel and its political impact. The negotiating is done by the reading public, i.e. by critics, readers and publishers.

What does this imply for the role and influence of fiction?

The novel “Native Son” shows that literature that engages with political issues has the potential to generate a whole new dimension of power when it combines different genres of writing – fictional, essayistic and autobiographical. What we can see here is a writing across different genres. Wright is, as far as I know, the first author in American literature to cultivate this kind of writing, the back and forth between different the fictional and the autobiographical.

In your book on “Belonging and Narratives”, you argue that novels can be used to evoke feelings of home and belonging. You say novels are “primary place and home making agents.” How important are novels and media networks for creating a sense of belonging?

Cultural representations and mediations always take place in social contexts. The use of society-building media is what keeps us together. By this I mean both the content of these media and the underlying webs of relations.

How can we succeed in building bridges using the media networks of today?

In present-day USA, these media networks create separate, antagonistic realities. Communication takes place in people’s personal bubbles, which are governed by their own values and rules. This is the obvious problem. How do you create media networks that rebuild bridges, that break down polarisation? How do you forge new alliances? What forms of communication would be useful to break down the entrenched camps? Is there even a point to it? Many scholars and commentators are of the opinion that talking to Trumpists or evangelicals is a waste of time.

Care to venture a prognosis for the future of the USA?

For a couple of decades now, the political and social situation in the country has been hardening, getting worse instead of better. It’s difficult to venture an optimistic prognosis, especially regarding the near future. 250 years ago, US democracy was radically new, and even then it was fundamentally flawed; today, it’s in dire need of modernisation, starting with the two-party system that has taken root and the lasting need to reckon with the legacy of slavery. My hope stems from my faith in the resilience of American democracy and its capacities for self-reform. But I also have serious concerns.

Social cohesion in the US is not possible without ...?

… a change in the debate culture and without the effort and commitment to establish that debate culture.