Neuroscience

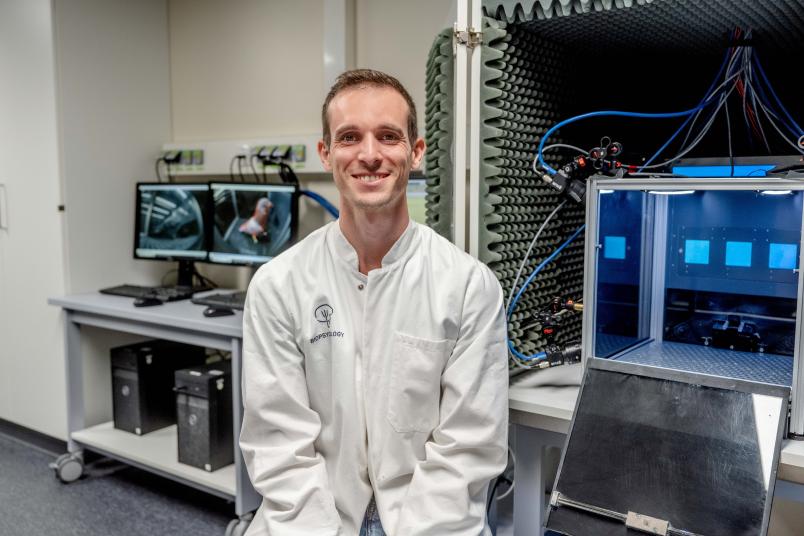

Guillermo Hidalgo Gadea researches cognitive processes

The PhD student is fascinated by the connection between body and brain, between behavior and thinking.

Looking at neuroscience, what is its most fascinating aspect for you?

I’m fascinated by the connection between body and brain, between behavior and thinking, and by how fundamental cognitive processes differ between individual humans, but also between us and other animals. For example, when I go shopping and plan my meals for the coming week, I make numerous complex decisions and trade-offs. I may be thinking about staying in shape for my upcoming vacation, or I may want to treat a friend and need to tailor my grocery shopping to their preferences. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that other people and other animals must have similar thought processes just because their behavior resembles mine. In neuroscience, these differences can be measured very nicely by comparing not only the solutions with each other, but also the calculation paths – just like we did in school.

What has been your most exciting research result so far?

Over the past few years, I’ve been trying to measure pigeon behavior as accurately as possible, mainly using machine learning, video analysis, and 3D reconstructions of animal body movements. By using these new methods, we’re trying to increase measurement accuracy, and at the same time we are making new behaviors measurable, which map the animals thought process (or calculation path) rather than just the solution or final decision.

We see in our experiments that pigeons exhibit exceedingly more varied behavior than what is necessary and expected for solving specific tasks. For example, a pigeon investigates distant feeders with pronounced head movements indicating visual attention, but ultimately decides against them and sticks to the closer alternative. Such suppressed decisions can’t be accounted for with usual measurement methods, because the pigeon doesn’t move in space and doesn’t physically interact with the alternative feeder.

Cognitive processes are not limited to the brain

Another example is when pigeons develop an individual and, more importantly, task-independent behavioral pattern to retain certain information in memory. They may turn their body in a certain direction, tilt their head in a certain way, or peck at a certain spot, and do so with varying frequency and strength to encode a decision. This behavior could perhaps be compared to me moving my fingers while doing mental arithmetic.

These results still need to be studied in greater detail, but so far all this fits very well with the theory and research direction of embodied cognition. According to this theory, cognitive processes are not limited to the brain, but take place in direct interaction with the body and the environment, in movement and behavior.

You completed your A-levels at a German school in Barcelona. How come you developed such strong ties with Germany, which eventually took you to Dortmund, Wuppertal and Bochum?

Well, that wasn’t my own doing, exactly. Even though my parents don’t speak any German to this day, they enrolled me in the German School in Barcelona when I was still in kindergarten – perhaps as an experiment? From then on, I was consistently drawn to Germany, and in a few weeks I’ll be celebrating my twelve-year immigration anniversary. Germany in general, and NRW in particular, are a great place to live, study and do research. The research groups in Bochum headed by Professor Onur Güntürkün and Professor Albert Newen are indeed very international; and by now I think more often in German than in Spanish.