History

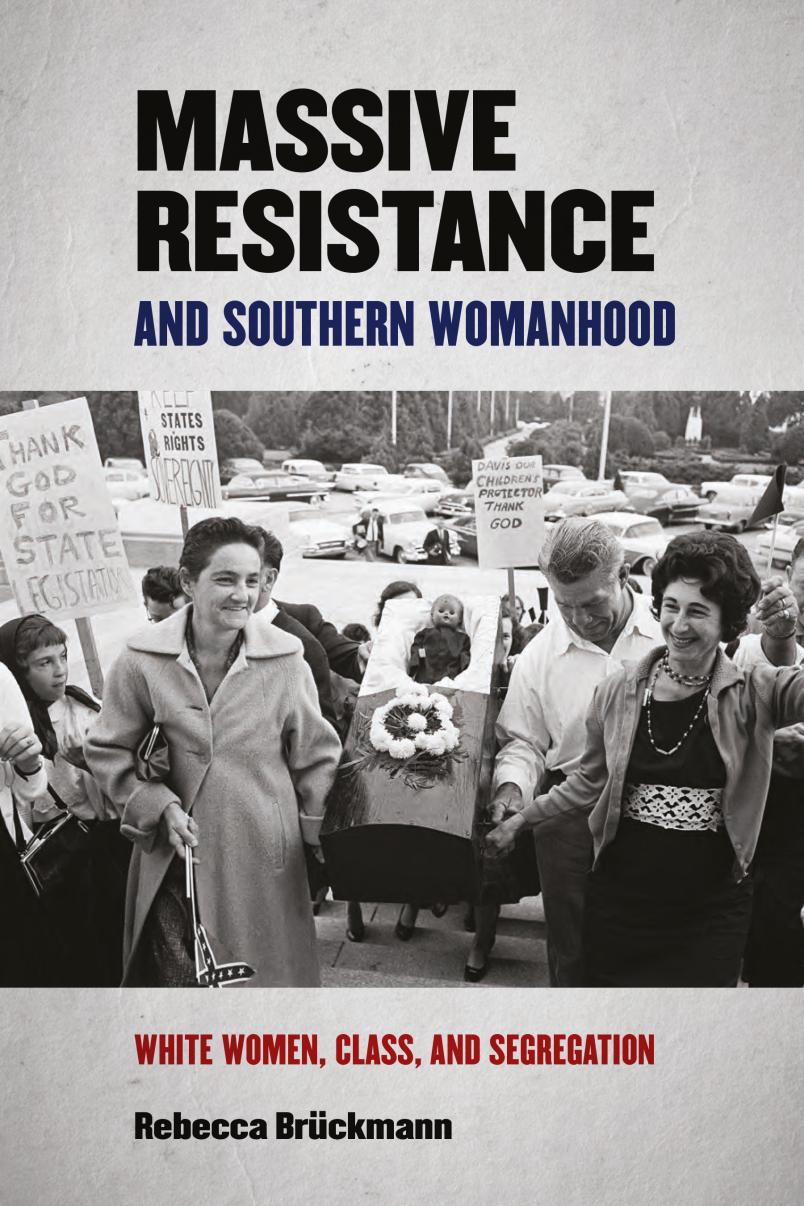

The racist violence of white women

In the 1950s and 1960s, women went to extreme lengths to fight against the desegregation of schools and other public spaces. An as yet neglected chapter in the history of racism.

In 1958 and 1959, all four high schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, remained closed for a whole year. The parents of the approximately 2,000 white students of Little Rock High School regarded their children as threatened. The threat consisted of nine black children who wanted to attend this school, too. The protest against desegregation, i.e., the lifting of racial segregation, went so far and became so violent that the US government eventually deployed the military.

Professor Rebecca Brückmann, assistant professor for the History of North America and Its Transcultural Context at RUB, has studied this protest of the white population in detail. She focuses primarily on the activities of women. “This part of history has been neglected for a long time,” as she explains her interest. She has compiled the results of her study in a book that will be published in early 2021.

Absolutely everything was designated for either white people or for black people

These white protests have a long history. They have their roots in British slavery in the USA, which has been documented since the beginning of the 17th century. In the middle of the 17th century, a law was passed in Virginia, stating that children inherit the status of their mothers: if the mother was enslaved, so were her children. Slavery and White Supremacy were closely entwined, and this supposed superiority of white people was maintained through the ban on the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 emancipation proclamation, and the prohibition of slavery with the Thirteenth Amendment two years later.

After Reconstruction, when the military withdrew from the southern states, the entire public sphere was divided in two. Absolutely everything was designated for either white people or for black people: park benches, cemeteries, blood banks, buses, schools. In 1896, the Supreme Court legitimised this separation on condition that all these facilities were of equal value. “They never were,” says Rebecca Brückmann. “And activists fought against it for 50 years more or less without success.”

Following the Second World War, they changed their strategy: they went to court. And in 1954, a verdict was passed that triggered the coordinated protest of white people. Racial segregation in public schools was declared unconstitutional. Segregation in schools violated the principle of equality. “Subsequently, massive resistance formed among white people; and the issue of public education and the fact that children were concerned served as a legitimization for mothers to get involved,” says Rebecca Brückmann.

In order to examine their behaviour, she analysed media sources, memoirs, manuscripts of citizens and school boards, and FBI records. Following the often violent protests of the mothers, the intelligence and security service interviewed the parties involved. Brückmann researched three cases in great detail, including that of the Mothers’ League of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Central High was closed for a year.

The mothers incited their children to bully black students. The decision to close the school was motivated by the conviction that it was better not to have any school at all than to teach white children together with black children. In another case in New Orleans, a crowd of women made an appearance in 1960 to protest against black children attending school, physically attacking black and white parents, and even threatening black children with death. This case involved four black children who had been admitted to two primary schools.

But it is always more complex than it looks.

Rebecca Brückmann

The police described the group as “cheerleaders”: an indication that they were considered supporters of the real actors of segregation, making a lot of noise but essentially harmless. “But they were, in fact, on the playing field, because the cheerleaders themselves were actors on the scene and were involved in protests, physical attacks on white parents who refused to join the boycott, and lobbying,” stresses Rebecca Brückmann. “This shows how the very masculinist discourse around the desegregation crises in the 1950s and 1960s led to the long-held assumption that women were mere symbols, rather than actors in their own right.” Participants included mothers, grandmothers, neighbours. They also included educated people, members of the upper class.

There is a reason why white people did that: they felt their status to be threatened. Women of the working class had no political voice in the USA of the 1950s. To gain attention, they resorted to new means and devised new tactics, all of which were based on ingrained racism. “But it is always more complex than it looks,” points out Brückmann.

Turning the tables

The women expanded the arguments of the debate. Their point was: today the state interferes in schools, tomorrow it will be the churches, next thing we know we will no longer decide anything. In doing so, they were turning the tables: our freedom is at stake. There is a real threat of reverse discrimination. In response, the so-called Massive Resistance emerged, demanding that the US government should keep out of the affairs of individual states. A new conservatism was spreading, and White Supremacy acted as a hinge. Religion, anti-communism, and, at a later point, traditional values against the 68ers – White Supremacy helped unite and consolidate many different movements. “White Supremacy always works. This plays a major role in the USA, and it is not just day-to-day politics,” says Rebecca Brückmann. “The current Black Lives Matter movement is also rooted in this history.”

Being white is much more than just skin colour. Appearance is only one aspect of the whole issue. Whiteness is the default, everything else is a deviation. It is about a social position, about power and space.

After the mothers’ protests against the admission of black pupils failed to have the desired effect, white people started boycotting the schools. They moved to the suburbs, which is something that not everyone can afford, and thus to other school districts. This was how they made sure that they stayed among themselves.

Interview