Interview “Even the electric torch was too bright”

Telescopes used in gamma astronomy are extremely sensitive, as astrophysicist Julia Tjus knows from experience.

Prof Tjus, you are in fact a theoretical researcher. But you have also gained practical experience in the field of gamma astronomy.

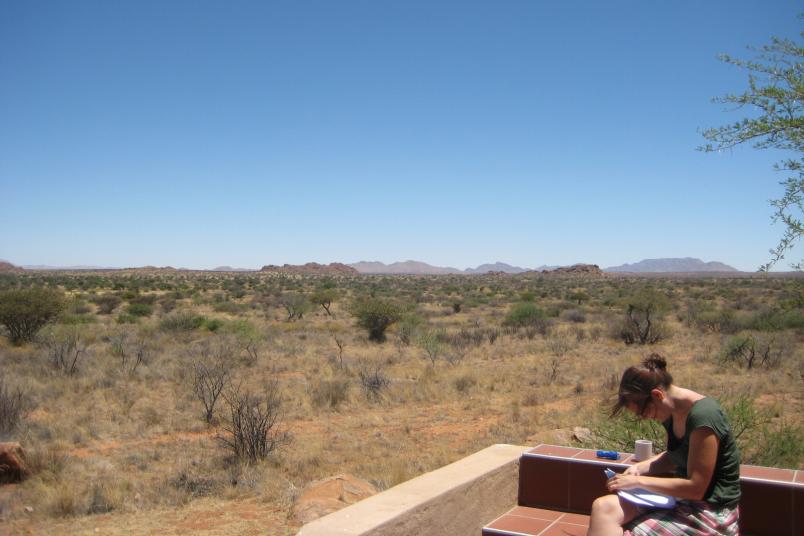

In 2010, I had the chance of doing a two-week shift at the HESS telescope in Namibia. It was great, being in the steppe and gathering experience in practice.

Which duties did you have?

I was not in charge, of course, but took part as a normal shift member. Like with all astronomical instruments, there is a control room with monitors to check if data recording is progressing smoothly. If we received an alert from another observatory, we discussed if we should also point our telescope in that direction. Another duty was to shut down the telescopes in good time and to make everything light-tight to ensure that no light hits the camera.

Why is that important?

Gamma radiation is visible in the form of weak bluish flashes that flare up for merely a few nanoseconds. They are not visible to the naked eye. Therefore, the detectors have to be extremely sensitive; too much light would oversaturate and destroy them. I remember that a red-light torch was all that I was permitted to use when I went to the dormitories during observation periods. Even a normal electric torch was too bright.

Even the light emitted by the moon was too much.

The observation conditions sound complicated.

In the past, such telescopes couldn’t be deployed on moonlit nights, because even the light emitted by the moon was too much. Today, detectors exist that can be used for conducting measurements even during full moon. Our colleague from Dortmund, Wolfgang Rhode, was involved in their development. Thus, the nights in gamma astronomy have become much longer. It used to be much less busy, because sometimes it wasn’t possible to record data for longer than an hour per night.