Biology An off switch for aggression

The way aggressive behaviour develops is still poorly understood. Researchers have now discovered a crucial piece of the jigsaw.

Researchers from Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB) and colleagues from Bonn have found a connection in the brain that is crucial for aggressive behaviour in mice. The so-called P/Q-type calcium channel, which reacts to the messenger substance serotonin, is key. It has been known for some time that serotonin plays a decisive role in emotion regulation. But it hasn’t been understood until now how exactly aggressive behaviour develops. Once the researchers switched off the serotonin-mediated connection between two specific brain regions, the mice behaved less aggressively. The team headed by Pauline Bohne and Professor Dr. Melanie Mark reports their findings in the “Journal of Neuroscience”, published online on 19 July 2022.

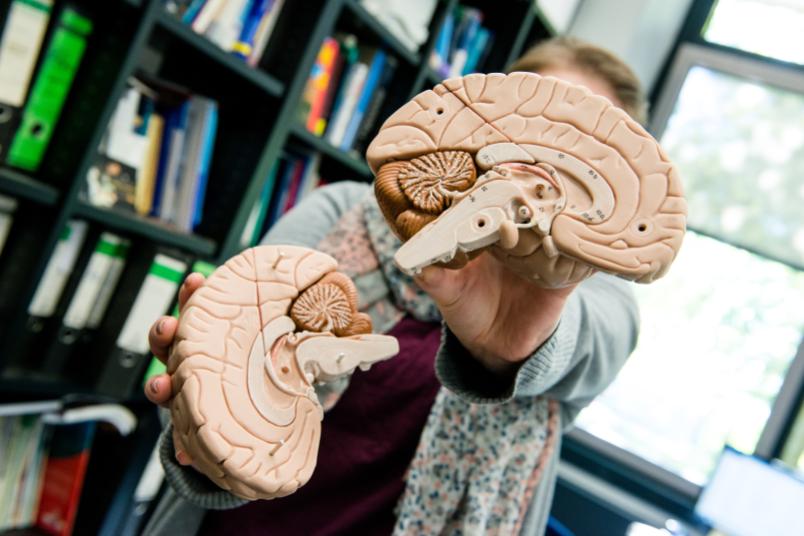

Visualising the connection between brain regions

The RUB team from the Behavioral Neurobiology research group, together with a colleague from Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, analysed a nucleus located deep in the brain, i.e. the dorsal raphe nucleus. As their research showed, this nucleus sends nerve fibres that react to the neurotransmitter serotonin to the ventromedial hypothalamus. The researchers made these visible with green fluorescent tracer substances.

Aggression switched on and off

In subsequent experiments, the researchers removed the P/Q-type calcium channel from the dorsal raphe nucleus in male mice. Brain activity in this nucleus and in the connected ventromedial hypothalamus increased – and so did the animals’ aggressive behaviour.

The team then introduced a modified receptor into the cells of the dorsal raphe nucleus of the same animals via genetic modification – as a replacement for the previously removed P/Q-type calcium channel. They were able to inhibit the modified receptor with a chemical molecule that doesn’t typically occur in mice. Using this molecule, the researchers slowly reduced the activity of the modified receptor and thus the activity of the nerve cells in the dorsal raphe nucleus. In doing so, they silenced the serotonin signal that the dorsal raphe nucleus normally sends to the ventromedial hypothalamus. This is how they tamed the previously aggressive mice, which now once again exhibited normal behaviour.

Aggression as comorbidity of mental illnesses

“The study proves that the P/Q-type calcium channel plays an important role in the serotonin system for aggression,” says Pauline Bohne. “Consequently, it is a potential approach for treating violent behaviour.” Aggressive behaviour is increasingly observed as a side effect of mental illnesses, such as anxiety disorders, impulse control disorders and childhood bipolar disorder, to name but a few. “People with such conditions who behave aggressively are not only a danger to staff in clinics, but also to themselves,” points out Melanie Mark. “Often, the treatment of the aggression prolongs their stay in the clinic and results in an increase of the associated costs.”