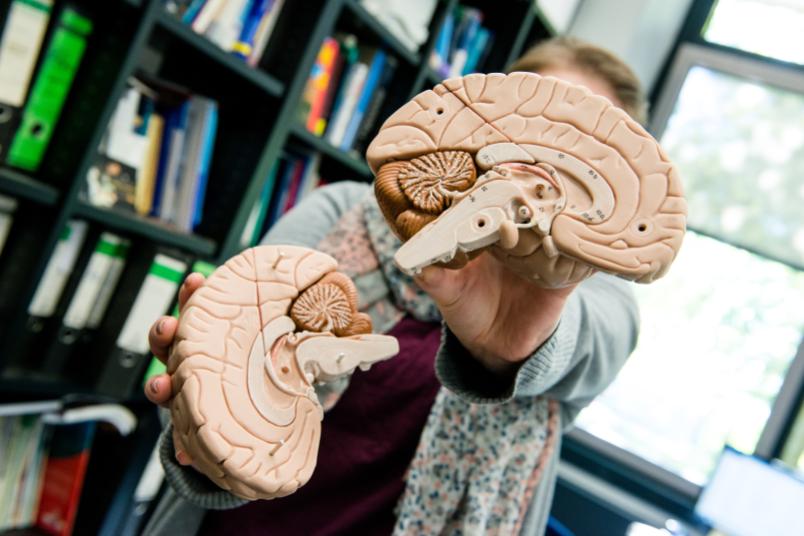

Neuropsychology Exercise to prevent dementia

A new study shows how effective it is to exercise body and mind.

Physical and mental exercise can prevent dementia. The training is particularly effective when body and mind are addressed at the same time. This is the conclusion of researchers from Bochum and Duisburg who compared the effects of combined and separate mental and physical exercise in people with mild cognitive impairment, a possible pre- stage of dementia. The team led by Vanessa Lissek and Professor Boris Suchan from the Clinical Neuropsychology research group at Ruhr-Universität Bochum, together with colleagues from Berufsgenossenschaftliches Klinikum (BG Clinic) Duisburg, describe the results in the Journal of Alzheimer Disease, published online on 13. September 2022.

In the “go4cognition” project, the researchers studied 39 people between the ages of 65 and 85 diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. “This is a kind of intermediate state,” explains Boris Suchan. “People are not yet impaired in their daily activities, but may develop dementia some time down the road.” In neuropsychological tests, they show evidence of certain cognitive changes. The team diagnosed mild cognitive impairment with the well established CERAD test and additional standard neuropsychological tests that measure cognitive functions such as memory, executive functions and attention. The researchers also assessed motor functions such as strength in the hands and balance.

Two types of exercise

The researchers subsequently divided the participants into two groups: one group of 24 people exercised their body and mind simultaneously with the so-called SpeedCourt system at the BG Clinic in Duisburg. This is a 5.5 by 5.5 metre mat system equipped with sensors. The participants had to run down the mats as quickly as possible in a sequence that had been presented to them beforehand. The remaining 15 people trained body and mind separately at the “Gute Hoffnung” retirement home in Oberhausen. They completed the Fitfür100 programme, a physical training with balance exercises that also strengthens the muscles. Their cognitive functions were stimulated by games during the breaks. Both training programmes lasted six weeks. Immediately after this period and three months later, the participants completed the same cognitive and motor tests as at the beginning of the study.

Both exercises effective

A statistical analysis showed that both interventions were equally effective against the deficits that had been revealed in cognitive tests before the training. Approximately 50 per cent of the participants improved their cognitive performance through the exercises to such an extent that the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment no longer applied to them after the training. These positive effects were still observed in tests three months after the intervention, even though the participants hadn’t undergone any additional training during this time.

Moreover, the participants achieved better results in the physical parameters of hand strength and balance after the training.